𝐂𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐱𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐎𝐫 ‘𝐂𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧’ 𝐈𝐧 𝐀𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐄𝐠𝐲𝐩𝐭?

Mohamad Mostafa Nassar

Twitter:@NassarMohamadMR

1. Introduction

It has been claimed by the Christian missionaries that the Qur’an is in error when it mentions crucifixion as a form of punishment in Egypt. They say:

We have, however, no record that Egyptians used crucifixion as punishment in the time of Moses (1450 BC, conservative date; 1200 BC at the latest) or even Joseph (1880 BC, conservative date). Crucifixion only becomes a punishment much later in history and then first in another culture before it has been taken over by the Egyptians. Such threats by a Pharaoh at these times are historically inaccurate.

The missionaries are certain that crucifixion as a distinct form of punishment was innovated by the Romans. Their analysis of the genesis of crucifixion can be summed up in just a dozen words. They say:

Simply put, crucifixion defines a method of execution used by the Romans…

As usual no documentation is provided to substantiate the missionaries claim – surprisingly, even the usual barrage of internet citations are not present. Such a situation is quite understandable because this statement is factually incorrect so one would search in vain for any supporting references. It is clear the missionaries have failed to take into account those periods of history preceding the Romans.

Such restricted reading has meant they are not fully aware of the genesis of crucifixion and the importance and meaning that are attached to certain words that aim to define crucifixion. So what does the Qur’an have to say about crucifixion? Certain parts of the Qur’an talk about crucifixion as a method of punishment in ancient Egypt during the time of Joseph and Moses.

𝐈𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐉𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐩𝐡, 𝐉𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐩𝐡 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐦 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐬:

O my two companions of the prison! As to one of you, he will pour out the wine for his lord to drink: and as for the other, he will be crucified, and the birds will eat from his head. Thus is the case judged concerning which you both did enquire. [Qur’an 12:41]

𝐀𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐱𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐬, 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐏𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐨𝐡’𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐏𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐨𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦 𝐛𝐲 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠:

Be sure I will cut off your hands and your feet on apposite sides, and I will cause you all to die on the cross. [Qur’an 7:124]

(Pharaoh) said: Ye put your faith in him before I give you leave. Lo! he doubtless is your chief who taught you magic! But verily ye shall come to know. Verily I will cut off your hands and your feet alternately, and verily I will crucify you every one. [Qur’an 26:49]

(Pharaoh) said: “Believe ye in Him before I give you permission? Surely this must be your leader, who has taught you magic! be sure I will cut off your hands and feet on opposite sides, and I will have you crucified on trunks of palm-trees: so shall ye know for certain, which of us can give the more severe and the more lasting punishment!” [Qur’an 20:71]

The Qur’an also supplies a very important piece of information concerning the Pharaoh. The Pharaoh is addressed as the Lord of the Stakes.

Before them (were many who) rejected apostles,- the people of Noah, and ‘Ad, and Pharaoh, the Lord of Stakes… [Qur’an 38:12]

Seest thou not how thy Lord dealt with the ‘Ad (people),-Of the (city of) Iram, with lofty pillars, The like of which were not produced in (all) the land? And with the Thamud (people), who cut out (huge) rocks in the valley? And with Pharaoh, Lord of Stakes? (All) these transgressed beyond bounds in the lands, And heaped therein mischief (on mischief). [Qur’an 89:6-12]

A key tool of Qur’anic exegesis is the internal relationships between material in different parts of the Qur’an, expressed by Qur’anic scholars as: al-Qur’an yufassiru baʿduhu baʿdan, i.e., different parts of the Qur’an explain each other. In other words, what is given in a general way in one place is explained in detail in another place. What is given briefly in one place is expanded in another.

Using this principle, we can see that the Pharaoh, who is addressed as the “Lord of Stakes”, perhaps used stakes for crucifying people. Also why is the Pharaoh called the “Lord of the Stakes” in the Qur’an? Was it because he was the one who had the supreme authority over who meted out the punishment of crucifixion? Did the mutilation of a person precede his crucifixion? This is something that we would like to investigate in this essay.

2. What Does The Arabic Root Ṣ-L-B Mean?

Any discussion regarding crucifixion in ancient Egypt mentioned in the Qur’an must begin with an analysis of the Arabic word used to describe it. The word used to describe crucifixion in the story of Joseph in 21:41 is yuṣlabu and in the story of Moses, ṣallibannakum is used in 7:124, 26:49 and 20:71.

They both derive from the root word Ṣ-L-B. Below is a selection of the relevant passages from Lisān Al-ʿArab of Ibn Manzur concerning the root ṣād-lām-bā’ that is frequently misunderstood to mean “crucify”.

We will see that such an understanding is a quick shortcut and that this root is more complex than the average Arabic speaker knows.

صلب: الصُّلْبُ والصُّلَّبُ: عَظْمٌ من لَدُنِ الكاهِل إِلى العَجْب، والجمع أَصْلُب وأَصْلاب وصِلَبَةٌ؛ أَنشد ثعلب

أَما تَرَيْني، اليَوْمَ، شَيْخاً أَشْيَبَا،* إِذا نَهَضْتُ أَتَشَكَّى الأَصْلُبا

ṣād-lām-bā’: ṣalb and ṣallab refer to a bone from the upper body to the waist [i.e., the backbone], its plural is aṣlub and aṣlāb and ṣilabah. Thaʿlab said in his poetry:

Do you see me today an old grown up man When I stand up, I suffer from my back [Arabic: aṣlub].

والصُّلْب من الظَّهْر، وكُلُّ شيء من الظَّهْر فيه فَقَارٌ فذلك الصُّلْب؛ والصَّلَبُ، بالتحريك، لغة فيه؛

And ṣalb refers to the back, and any part of the back having vertebraes is called ṣalb; ṣalab with a vowel is another variant.

والصَّلابَةُ: ضدُّ اللِّين صَلُبَ الشيءُ صَلابَـةً فهو صَلِـيبٌ وصُلْب وصُلَّب وصلب أَي شديد. ورجل صُلَّبٌ: مثل القُلَّبِ والـحُوَّل، ورجل صُلْبٌ وصَلِـيبٌ : ذو صلابة؛ وقد صَلُب، وأَرض صُلْبَة، والجمع صِلَبَة. ويقال: تَصَلَّبَ فلان أَي تَشَدَّدَ. وقولهم في الراعي: صُلْبُ العَصا وصَلِـيبُ العَصا، إِنما يَرَوْنَ أَنه يَعْنُفُ بالإِبل؛

And ṣalābah is the opposite of softness [Arabic: līn]. We say of something that it has ṣaluba [i.e., hardened/stiffened], ṣalābatan [i.e., hardness/stiffness] and that it is ṣalīb and ṣulb and ṣullab meaning that it is hard.

And we say of a man that he is ṣullab [i.e., hard] on the same pattern as qullab and ḥuwwal and we say of him that he is ṣulb [i.e., hard] and ṣalīb [i.e., hard] and that he shows ṣalābah [i.e., hardness] and that he has ṣaluba [i.e., hardened] and we qualify a land of ṣulbah [i.e., hard/rocky]. And it is said: someone ta ṣallaba meaning that he grew severe/inflexible.

They also qualify a sheperd of ṣulb ul-ʿasā [i.e., having a hard staff] and ṣalīb ul-ʿasā when they think he is violent with the camels [in other words, the sheperd is so qualified when he hits his camels hard].

والنِّيقُ: أَرْفَعُ مَوْضِـعٍ في الجَبَل وصَلَبَ العِظامَ يَصْلُبُها صَلْباً واصْطَلَبَها: جَمَعَها وطَبَخَها واسْتَخْرَجَ وَدَكَها لِـيُؤْتَدَم به، وهو الاصْطِلابُ، وكذلك إِذا شَوَى اللَّحْمَ : فأَسالَه؛ قال الكُمَيْتُ الأَسَدِيّ

واحْتَلّ بَرْكُ الشِّـتاءِ مَنْزِلَه، * وباتَ شَيْخُ العِـيالِ يَصْطَلِبُ

And we say that someone ṣalaba some bones yaṣlubuhā ṣalban and he iṣtalaba the bones meaning that he collected the bones, cooked them and extracted their grease or oily matter [i.e., wadak] to be used as food, and this act is called iṣtilāb. Also when you grill some meat so that it melts. Al-Kumayt al-Asadī said:

The beginning of the cold came and the old man cooked/melted [meat].

وفي الحديث: أَنه لـمَّا قَدِمَ مَكَّةَ أَتاه أَصحابُ الصُّلُب؛ قيل: هم الذين يَجْمَعُون العِظام إِذا أُخِذَت عنها لُحومُها فيَطْبُخونها بالماءِ، فإِذا خرج الدَّسَمُ منها جمعوه وائْتَدَمُوا به. يقال اصْطَلَبَ فلانٌ العِظام إِذا فَعَل بها ذلك. والصُّلُبُ جمع صَليب، والصَّلِـيبُ: الوَدَكُز والصَّلِـيبُ والصَّلَبُ: الصديد الذي يَسيلُ من الميت. والصَّلْبُ: مصدر صَلَبَه يَصْلُبه صَلْباً، وأَصله من الصَّلِـيب وهو: الوَدَك. وفي حديث عليّ: أَنه اسْتُفْتِـيَ في استعمال صَلِـيبِ الـمَوْتَى في الدِّلاءِ والسُّفُن، فَـأَبـى عليهم، وبه سُمِّي الـمَصْلُوب لما يَسِـيلُ من وَدَكه. والصَّلْبُ، هذه القِتْلة المعروفة، مشتق من ذلك، لأَن وَدَكه وصديده يَسِـيل. وقد صَلَبه يَصْلِـبُه صَلْباً، وصَلَّبه، شُدِّدَ للتكثي وفي التنزيل العزيز: وما قَتَلُوه وما صَلَبُوه. وفيه: ولأُصَلِّـبَنَّكم في جُذُوعِ النَّخْلِ؛ أَي على جُذُوعِ النخل. والصَّلِـيبُ: الـمَصْلُوبُ. والصَّليب الذي يتخذه النصارى على ذلك الشَّكْل.

And in the ḥadīth: “When he came to Makkah, the makers of ṣalub came to him. It was said that they are the ones who collect bones after meat was removed and cook them in water. When the fat appears they collect it and ate it. We say that someone iṣtalaba the bones when he does so with the bones.

As for ṣalub, it is the plural of ṣalīb which means wadak.” Ṣalīb and ṣalab also refer to the pus that leaks from the dead. Ṣalb is the infinitive form of ṣalab [past form], yaṣlubu [present form], it is derived from ṣalīb which is the wadak. And in the ḥadīth of ʿAlī, he was asked about the use of the ṣalīb of the dead for crafting [dilā’] and boats and he forbade it.

And so was called the “crucified” because of the [wadak] that leaks from him. And ṣalb is that famous death [i.e., crucifixion] which is derived from the same origin because the wadak of the dead and his ichor leaks.

The verb is ṣalaba [past form], yaṣlubu [present form], ṣalban [infinitive form], ṣallaba is the exagerated form implying multiplicity. And in the Holy Revelation [i.e., the Qur’an]: wa mā qatalūhu wa mā ṣalabūhu [“they did not kill him or they crucified him”]. There is also: wa la’u ṣallibannakum fī judhūʿ in-nakhl meaning “on the trunks of palm trees”. Ṣalīb also refers to maṣlūb, “the crucified”. Ṣalīb is what the Christians take [as a symbol] of that form.

𝐅𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐧𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐞𝐝.

- The root word Ṣ-L-B derives from bone, more specifically the backbone.

- Ṣ-L-B is also used to denote hardness in a true as well as a metaphoric sense.

- Cooking the bones and extracting the greasy or fatty matter from it (wadak) – this action is called iṣtalaba, a word which comes from the root Ṣ-L-B.

- More importantly, ṣalb, commonly translated as “crucifixion”, comes from the root Ṣ-L-B and is derived from it because the wadak of the dead and his ichor (i.e., thin watery or blood-tinged discharge) leaks. Ibn Manzur in his Lisān Al-ʿArab gives two examples of its usage from the Qur’an, one referring to the time of Jesus and the other to the time of Moses, viz., Qur’an 4:157, wa mā qatalūhu wa mā ṣalabūhu [“they did not kill him or they crucified him”] and Qur’an 20:71, wa la’u ṣallibannakum fī judhūʿ in-nakhl [“I will have you crucified on trunks of palm-trees”], respectively.

- The Christian missionaries claimed that the “Arabic word for crucifixion used in the Qur’an refers to a cross-shaped instrument of execution” without any attempt to look into the etymological dictionaries. Edward Lane’s comprehensive An Arabic-English Lexicon has a three-page long discussion of the root word Ṣ-L-B, most of it is concentrated on the usage to mean “hard”, “firm”, etc. While dealing with the issue of crucifixion, Lane says: “[He crucified him;] he put him to death in a certain well-known manner… because the oily matter, and the ichor mixed with blood, of the person so put to death flows.”[1] Similar discussion, albeit a lot less comprehensive than Lane’s Lexicon, is also to be found in Hans – Wehr Dictionary Of Modern Written Arabic and in dictionaries devoted to the usage of Ṣ-L-B in the Qur’an.[2] We can now conclude that the root word Ṣ-L-B has neither any connotations of a cross nor of the shape of a cross; rather these two are derived meanings. As we have seen, Ṣ-L-B is used to denote hardness or stiffness and/or leaking oily matter from the body when crucified or impaled.

- In order to distract the readers from the discussion of the root word Ṣ-L-B, the missionaries quote Arthur Jeffery who alleged that the root Ṣ-L-B “cannot be explained from Arabic” and has its ultimate origins from either Persian or Ethiopic.[3] The missionaries misconstrue Jeffery’s statement to mean that “this term is not Arabic” even though Jeffery cites its usage in the pre-Islamic Arabic poetry of al-Nābigha and ʿAdi b. Zaid! With a narrow focus on some of the derived meanings of Ṣ-L-B which are “to crucify” or “cross”, the missionaries claim that the Arabic term used in the Qur’an refers “clearly to a geometric cross and not a pole, a stake, or a tree”. Had there been a genuine interest to establish the levels of meaning associated with the root Ṣ-L-B recourse would have been made to scholarly classical Arabic lexicons which discuss in detail the etymology of the root Ṣ-L-B. Calling the root Ṣ-L-B “foreign” is a mere distraction and as we have discussed, the root Ṣ-L-B has no connotations of a cross, a geometric cross, a pole, a stake or a tree.

In summary, the mention of crucifixion in the Qur’an comes from the root Ṣ-L-B and it has no connotations of a cross or its shape. Rather it indicates any method of execution which makes the body stiffened or hardened (as any movement would cause excruciating pain) and results in leaking of bodily fluids. Therefore, crucifixion by impalement and other forms of crucifixion are included here without making any distinction between them.

The Qur’anic usage originating from the root Ṣ-L-B appears to find common ground with what modern studies suggest about crucifixion in antiquity. It is almost always true that the word “crucifixion” brings a picture of the cross in the human mind. However, in antiquity people were “suspended”, “impaled” and “crucified”. The terms used to describe these English words were hardly distinguishable. This was pointed out by David Chapman in his recent study of crucifixion in antiquity. He says:

… in studying the ancient world the scholar is wise not to differentiate too rigidly the categories of “crucifixion,” “impalement,” and “suspension” (as if these were clearly to be distinguished in every instance). Hence any study of crucifixion conceptions in antiquity must grapple with the broader context of the wide variety of penal suspension of human beings.[4]

Furthermore, he says that in the past, “crucifixion” and “suspension” were not perceived by people in antiquity as wholly different spheres of punishment. Chapman adds that crucifixion “on a cross was simply one specific form within the broader category of human bodily suspension”.[5] Keeping this in mind, let us look at some of the definitions offered for crucifixion and cross in modern times.

3. Cross, Crucifixion And Punishment In Greek, Latin & English

The terms ‘crucifixion’ and ‘cross’ are widely used but what do they really mean? In the sections which follow we shall attempt to define these terms as accurately and as concisely as possible. Although crucifixion did not originate with the Romans, many reference works tend to discuss only the Roman method of crucifixion used in the time of Christ.

To avoid such a limited understanding, numerous references are consulted from original language lexicons, encyclopaedia entries and exegetical dictionaries in order establish the correct meaning and interpretation of these terms.

WHAT IS A CROSS?

According to the Christian missionaries,

A stake is not a cross;

As much as one would like to accept the missionaries’ understanding as to what constitutes a ‘cross’, one is on somewhat safer ground by returning to the appropriate lexicographical resources. The English word cross is a translation of the Greek σταυρός. The cross (Greek stauros; Latin crux) was originally a single upright stake or post upon which the victim was either tied, nailed or impaled. The standard lexicographical work of the ancient Greek language the Liddell-Scott-Jones-McKenzie’s A Greek-English Lexicon defines ‘cross’ as an,

upright pale or stake.[6]

The same or similar definitions can be found in Bauer-Danker-Arndt-Gingrich’s A Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament And Other Early Christian Literature,[7] Mounce’s The Analytical Lexicon To The Greek New Testament,[8] Louw and Nida’s Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament: Based On Semantic Domains[9] and Friberg, Friberg and Miller’s Analytical Lexicon Of The Greek New Testament.[10] The noun occurs twenty-seven times in the New Testament and it simply designates an upright stake.[11]

As one will observe it is lexically inappropriate to limit this word’s semantic domain to its specific usage in the Greek New Testament; to permit such would do violence to the word’s overall historical meaning. With no sound grasp of proper linguistic procedure, the missionaries fall headfirst over themselves in their haste to define the word ‘cross’ suitable for their purposes without consulting the required references.

Regarding the meaning of this word Nelson’s Illustrated Bible Dictionary defines the “Cross” as:

an upright wooden stake or post on which Jesus was executed… the Greek word for cross referred primarily to a pointed stake used in rows to form the walls of a defensive stockade.[12]

Vine’s Expository Dictionary Of New Testament Words defines the Greek word stauros as:

Stauros denotes, primarily, “an upright pale or stake.” On such malefactors were nailed for execution…

The method of execution was borrowed by the Greeks and Romans from the Phoenicians. The stauros denotes (a) “the cross, or stake itself,” e.g., Matt. 27:32; (b) “the crucifixion suffered,” e.g., 1 Cor. 1:17,18, where “the word of the cross,” RV, stands for the Gospel; Gal. 5:11, where crucifixion is metaphorically used of the renunciation of the world, that characterizes the true Christian life; Gal. 6:12,14; Eph. 2:16; Phil. 3:18.[13]

According to A Dictionary of Bible, Dealing With Its Language, Literature And Contents, Including The Biblical Theology, in New Testament usage the word stauros seems only to refer to the true “cross”:

[Stauros] means properly a stake, and is the tr. [i.e., translation] not merely of the Latin crux (cross), but of palus (stake) as well. As used in NT, however, it refers evidently not to the simple stake used for impaling, of which widespread punishment crucifixion was a refinement, but to the more elaborate cross used by the Romans in the time of Christ.[14]

The opinion that the New Testament usage of stauros refers only to the true “cross” is not strictly true. The term stauros actually has a much wider application, being used to refer to both a single stake and a crossbeam.

In Hastings’ Dictionary Of The Bible he states:

The Greek term rendered ‘cross’ in the English NT is stauros (stauroo = ‘crucify’), which has a wider application than we ordinarily give to ‘cross’ being used of a single stake or upright beam as well as of a cross composed of two beams.[15]

In New Testament usage stauros primarily refers to an upright stake or beam used as an instrument for punishment:

The Greek word for ‘cross’ (stauros; verb stauroo; Latin crux, crucifigo, ‘I fasten to the cross’) means primarily an upright stake or beam, and secondarily a stake used as an instrument for punishment and execution. It is used in this latter sense in the New Testament.[16]

The word stauros had at least three different meanings in the New Testament alone. The plank which supports the arms of the victim (patibulum in Latin) was itself called stauros (Luke 23:26); the stake or tree trunk on which the patibulum was nailed was also called stauros (John 19:19); and the whole complex together (patibulum and stake) was also called stauros (John 19:25).[17]

The Catholic Encyclopaedia (under “Archaeology of the Cross and Crucifix“) mentions that a primitive form of crucifixion on trees had long been in use, and that such a tree was also known as a cross:

The penalty of the cross goes back probably to the arbor infelix, or unhappy tree, spoken of by Cicero (Pro, Rabir., iii sqq.) and by Livy, apropos of the condemnation of Horatius after the murder of his sister. According to Hüschke (Die Multa, 190) the magistrates known as duoviri perduellionis pronounced this penalty (cf. Liv., I, 266), styled also infelix lignem (Senec., Ep. ci; Plin., XVI, xxvi; XXIV, ix; Macrob., II, xvi).

This primitive form of crucifixion on trees was long in use, as Justus Lipsius notes (“De cruce”, I, ii, 5; Tert., “Apol.”, VIII, xvi; and “Martyrol. Paphnut.” 25 Sept.). Such a tree was known as a cross (crux). On an ancient vase we see Prometheus bound to a beam which serves the purpose of a cross.

A somewhat different form is seen on an ancient cist at Præneste (Palestrina), upon which Andromeda is represented nude, and bound by the feet to an instrument of punishment like a military yoke – i.e. two parallel, perpendicular stakes, surmounted by a transverse bar. Certain it is, at any rate, that the cross originally consisted of a simple vertical pole, sharpened at its upper end.

Mæcenas (Seneca, Epist. xvii, 1, 10) calls it acuta crux; it could also be called crux simplex. To this upright pole a transverse bar was afterwards added to which the sufferer was fastened with nails or cords, and thus remained until he died, whence the expression cruci figere or affigere (Tac., “Ann.”, XV, xliv; Potron., “Satyr.”, iii)…

According to the Christian missionaries,

Crucifixion is a method of execution or “putting a living person on a cross in order to kill him”, …

What documentation do the missionaries provide in order to substantiate their “definition”? – their own musings. They say, “Christians know the definition of crucifixion, after all, our Lord suffered crucifixion.” Again, as much as one would like to accept the missionaries’ understanding as to what constitutes ‘crucifixion’, one is on somewhat safer ground by returning to the appropriate lexicographical resources. The noun “crucifixion” does not occur in the New Testament, but the corresponding verb “to crucify” appears frequently.[18] Liddell-Scott-Jones-McKenzie’s A Greek-English Lexicon defines ‘crucify’ as,

Fence with pales.[19]

It is only later the word acquired the meaning to fix, fasten, nail, hang a person on a cross. The same or similar definitions and explanations can be found in Bauer-Danker-Arndt-Gingrich’s A Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament And Other Early Christian Literature,[20] Mounce’s The Analytical Lexicon To The Greek New Testament,[21] Louw and Nida’s Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament: Based On Semantic Domains[22] and Friberg, Friberg and Miller’s Analytical Lexicon Of The Greek New Testament.[23]

The Oxford Companion to the Bible defines “Crucifixion” as:

The act of nailing or binding a person to a cross or tree, whether for executing or for exposing the corpse.[24]

Similarly, the Anchor Bible Dictionary defines “Crucifixion” as:

The act of nailing or binding a living victim or sometimes a dead person to a cross or stake (stauros or skolops) or a tree (xylon).[25]

The New Catholic Encyclopaedia defines “Crucifixion” as:

Crucifixion developed from a method of execution by which the victim was fastened to an upright stake either by impaling him on it or by tying him to it with thongs… From this form of execution developed crucifixion in the strict sense, whereby the outstretched arms of the victim were tied or nailed to a crossbeam (patibulum), which was then laid in a groove across the top or suspended by means of a notch in the side of an upright stake that was always left in position at the site of execution.[26]

And in discussing the Christian belief in the crucifixion of Christ, Nelson’s Illustrated Bible Dictionary defines “Crucifixion” as:

the method of torture and execution used by the Romans to put Christ to death. At a crucifixion the victim usually was nailed or tied to a wooden stake and left to die…

Crucifixion involved attaching the victim with nails through the wrists or with leather thongs to a crossbeam attached to a vertical stake…[27]

Crucifixion then can be understood as the act of nailing, binding or impaling a living victim or sometimes a dead person to a cross, stake or tree whether for executing the body or for exposing the corpse. Crucifixion was commonly practiced from the 6th century BCE until the 4th century CE, when it was finally abolished in 337 CE by Constantine I. It was intended to serve as both a severe punishment and a frightful deterrent to others and was unanimously considered the most horrible form of death.

ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH WORDS “CRUCIFIXION” & “CROSS”

The Greek word for cross stauros (Latin crux) refers primarily to an upright stake or pole.[28] As we have mentioned, the noun “crucifixion” does not occur in the New Testament, but the corresponding verb “to crucify” appears frequently.[29] In classical Greek usage, the root verb stauroo actually means “to impale” or “to fence with pales” (Liddell-Scott-Jones-McKenzie’s A Greek-English Lexicon). However, there appears to be no common word for the “cross” in Greek, as the word crux (cross) in Latin. The Concise Dictionary Of The Bible states under “Cross”:

Except the Latin crux there was no word definitively and invariably applied to this instrument of punishment [i.e. cross].[30]

Concerning the origin of the Latin crux Merriam-Webster’s Word Histories states:

..the Latin noun crux ‘cross, gibbet’ was taken into Old French as crois and into Spanish as cruz…

The original sense of crux in classical Latin was an instrument of torture, whether gibbet, cross, or stake. By extension it meant ‘torture, trouble, misery’. With this in mind, English borrowed crux in the sense of ‘a puzzling or difficult problem’. From this sense developed its use for ‘an essential point requiring resolution’, as in “the crux of a problem,” and the sense of ‘a main or central feature’, as in “the crux of an argument.”[31]

Lewis & Short Latin Dictionary also mentions the same meanings:

a tree, frame, or other wooden instruments of execution on which criminals were impaled or hanged.[32]

Furthermore, the word crux is the core of several English words including “crucifixion”:

The Latin crux is also the core of the English words crucial, crucifix, crucifixion, cruciform, crucify, and excruciating. The English cross derives from crux through either Old Irish or Old Norse. The English cruise also derives from crux, which became crucen ‘to make a cross’ in Middle Dutch and kruisen ‘to sail crossing to and fro’ in Modern Dutch before being borrowed into English in the seventeenth century.[33]

Crucifixion is the act of nailing, binding or impaling a living victim or sometimes a dead person to a cross, stake or a tree, whether for executing the body or for exposing the corpse. Crucifixion was intended to serve as both a severe punishment and a frightful deterrent to others. It was unanimously considered the most horrible form of death.

The cross (Greek stauros; Latin crux) was originally a single upright stake or post upon which the victim was either tied, nailed or impaled. This simple cross was later modified when horizontal crossbeams of various types were added. Scholars are not certain when a crossbeam was added to the simple stake, but even in the Roman period the cross would at times only consist of a single vertical stake.

In many cases, especially during the Roman period, the execution stake became a vertical pole with a horizontal crossbar placed at some point, and although the period of time at which this happened is uncertain, what is known is that this simple impalement became known as crucifixion. Whether the victim was tied, nailed or impaled to the stake, the same Greek words were still used to describe the procedure.

Although in New Testament usage the Greek word stauros (cross) is sometimes said to refer to a crossbeam, the term actually has a much wider application, being used to refer to both a single stake and a crossbeam. The four most popular representations of the cross are: (i) crux simplex |, a “single piece without transom”; (ii) crux decussata X, or St. Andrew’s cross; (iii) crux commissa T, or St. Anthony’s cross; and (iv) crux immisaa or Latin cross upon which Jesus was allegedly crucified.[34]

A primitive form of crucifixion on trees had long been in use, and such a tree was also known as a cross (crux). Different ideas also prevailed concerning the material form of the cross, and it seems that the word had been frequently used in a broad sense.

The Latin word crux was applied to the simple pole, and indicated directly the nature and purpose of this instrument, being derived from the verb crucio, “to torment”, “to torture.” The practice of crucifixion was finally abolished in 337 by Constantine I out of respect for Jesus Christ, whom he believed died on the cross.

4. Crucifixion In Antiquity

Martin Hengel, Professor of New Testament and Early Judaism studies at Tübingen University, Germany, stresses that all attempts to give a perfect description of the crucifixion in archaeological terms are in vain as there were just too many different possibilities. He says:

All attempts to give a perfect description of the crucifixion in archaeological terms are therefore in vain; there were too many different possibilities for the executioner. Seneca’s testimony speaks for itself:

I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet.[35]

Although the procedure was subject to wide variation according to the whim and sadism of the executioner, victims were often executed by being suspended on a pole or impaled on a stake. In antiquity, the form of execution was less important than the fact that the person was executed. Chapman says:

… generally in antiquity the form of penal bodily suspension was less significant than the fact that body was being suspended… It seems that crucifixion was often widely regarded in the ancient world as being within the general conceptual field of human bodily suspension.[36]

The earliest reference to crucifixion by impalement is found in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1700 BCE). It says:

153. If a seignoir’s wife has brought about the death of her husband because of another man, they shall impale that woman on stakes.[37]

With reference to the Code of Hammurabi, Ford considered this as the first documented instance of the crucifixion of women in antiquity. He said,

Crucifixion (impalement) is found in the Code of Hammurabi. The punishment for breaking through a wall in a house was death followed by impalement. Impalement after death reflects the crime; he pierced the wall, so his body is pierced. But another, even grosser punishment is inflicted upon an adulterous woman who instigated the death of her husband for the sake of her lover. In Code of Hammurabi, 153 we read: “If a woman has procured the death of her husband on account of another man, they shall impale that woman.”[38]

Let us now consider some other examples of crucifixion in antiquity which are invoked in the scholarly literature.

CRUCIFIXION IN ANCIENT ASSYRIA

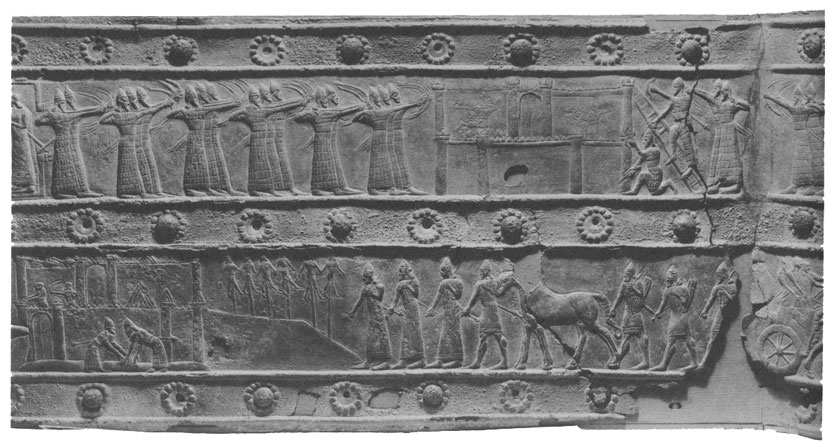

Perhaps one of the best examples of the variation of crucifixion in the form of impaling the enemies comes from the times of the Assyrian ruler Shalmaneser III (859 BCE – 824 BCE). Figures 1 and 2 show people being impaled or suspended by a stake through their private parts and chests, respectively.

Figure 1: Shalmaneser III’s campaign in north Syria: town of Dabigu (top), impaled inhabitants of Syrian town (below). Also notice that the inhabitants have been impaled by a stake through their private parts.[39]

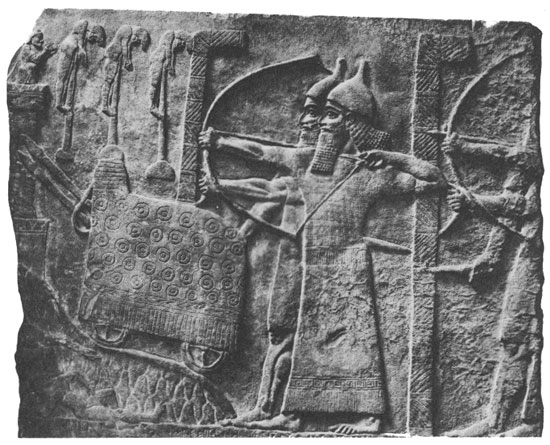

Figure 2: Attack of the walls of a town by a seige-engine supported by bowmen protected by shields. The bodies of the three townsmen are impaled outside the wall. Here the stake went through the chest.[40]

The famous account for the evidence of the Assyrian crucifixion, often repeated in the scholarly literature, is that of Assyrian king Ninus who had the Median king Pharnus crucified.

ὁ δὲ ταυτ́ης βασιλεὺς Φαρνος παραταξάμενος ἀξιολόγω δυνάμει καὶ λειφθείς, τω̂ν τε στρατιωτω̂ν τοὺς πλείους ἀπέβαλε καὶ αὐτὸς μετὰ τέκνων ἑπτὰ καὶ γυναικὸς αἰχμάλωτος ληφθεὶς ἀνεσταυρώθη.

ho de tautis basileus Parnos parataxamenos axiologo dunamei kai leiphtheis, tôn te stratiotôn tous pleious apebale kai autos peta teknon epta kai gunaikos aichmalotos lêphtheis anestaurôthi.

And the king of this country, Pharnus, meeting him in battle with a formidable force, was defeated, and he both lost the larger part of his soldiers, and himself, being taken captive, along with his seven sons and wife, and crucified.[41]

The English translation uses the word “crucified” which is the translation of the Greek word anestaurôthi from the verb anastauroô meaning “to impale”. This word is now usually translated to mean “impale” in the literature.[42] It should be noted, however, that it is believed that the report of Diodorus has no historical value.[43]

Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the example of crucifixion given in early Assyrian times was nothing but impalement. In spite of the evidence of crucifixion by impalement in the Code of Hammurabi and in Assyria, many authors wrongly refer to Herodotus’ (5th century BCE) writings to claim that the earliest references of crucifixion comes from Persia.[44]

HERODOTUS’ ACCOUNTS OF CRUCIFIXION

Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, Anatolia not long after 480 BCE and died some time between 430-420 BCE.[45] Herodotus refers to the stake as a method of execution, but also gives an example of a victim being nailed on a board. We will discuss a few instances where he mentions impalement in his Histories.

1.128. [1] διαλυθέντος δὲ του̂ Μηδικου̂. στρατεύματος αἰσχρω̂ς, ὡς ἐπύθετο τάχιστα ὁ ̓Αστυάγης, ἔφη ἀπειλέων τῳ̂ Κύρῳ “ἀλλ’ οὐδ’ ὣς Κυ̂ρός γε χαιρήσει.” [2] τοσαυ̂τα εἰ̂πας πρω̂τον μὲν τω̂ν Μάγων τοὺς ὀνειροπόλους, οἵ μιν ἀνέγνωσαν μετει̂ναι τὸν Κυ̂ρον, τούτους ἀνεσκολόπισε, μετὰ δὲ ὥπλισε τοὺς ὑπολειφθέντας ἐν τῳ̂ ἄστεϊ τω̂ν Μήδων, νέους τε καὶ πρεσβύτας ἄνδρας. [3] ἐξαγαγὼν δὲ τούτους καὶ συμβαλὼν τοι̂σι Πέρῃσι ἑσσώθη, καὶ αὐτός τε ̓Αστυάγης ἐζωγρήθη καὶ τοὺς ἐξήγαγε τω̂ν Μήδων ἀπέβαλε.

[1.128.1] dialuthentos de tou Mêdikou. strateumatos aischrôs, hôs eputheto tachista ho Astuagês, ephê apeileôn tôi Kurôi “all’ oud’ hôs Kuros ge chairêsei.” [1.128.2] tosauta eipas prôton men tôn Magôn tous oneiropolous, hoi min anegnôsan meteinai ton Kuron, toutous aneskolopise, meta de hôplise tous hupoleiphthentas en tôi asteï tôn Mêdôn, neous te kai presbutas andras. [1.128.3] exagagôn de toutous kai sumbalôn toisi Perêisi hessôthê, kai autos te Astuagês ezôgrêthê kai tous exêgage tôn Mêdôn apebale.

[1.128.1] Thus the Median army was foully scattered. Astyages, hearing this, sent a threatening message to Cyrus: “that even so he should not go unpunished”; [1.128.2] and with that he took the Magians who interpreted dreams and had persuaded him to let Cyrus go free, and impaled them; then he armed the Medes who were left in the city, the youths and the old men. [1.128.3] Leading these out, and encountering the Persians, he was worsted: Astyages himself was taken prisoner, and lost the Median army which he led.[46]

Note that the English translation uses the word “impaled” which is the translation of the Greek word anaskolopise from the verb anaskolopizô meaning “to fix on a pole or stake, to impale”.

3.125 [3] ἀποκτείνας δέ μιν οὐκ ἀξίως ἀπηγήσιος ̓Οροίτης ἀνεσταύρωσε: τω̂ν δέ οἱ ἑπομένων ὅσοι μὲν ἠ̂σαν Σάμιοι, ἀπη̂κε, κελεύων σφέας ἑωυτῳ̂ χάριν εἰδέναι ἐόντας ἐλευθέρους, ὅσοι δὲ ἠ̂σαν ξει̂νοί τε καὶ δου̂λοι τω̂ν ἑπομένων, ἐν ἀνδραπόδων λόγῳ ποιεύμενος εἰ̂χε. [4] Πολυκράτης δὲ ἀνακρεμάμενος ἐπετέλεε πα̂σαν τὴν ὄψιν τη̂ς θυγατρός: ἐλου̂το μὲν γὰρ ὑπὸ του̂ Διὸς ὅκως ὕοι, ἐχρίετο δὲ ὑπὸ του̂ ἡλίου, ἀνιεὶς αὐτὸς ἐκ του̂ σώματος ἰκμάδα.

[3.125.3] apokteinas de min ouk axiôs apêgêsios Oroitês anestaurôse: tôn de hoi hepomenôn hosoi men êsan Samioi, apêke, keleuôn spheas heôutôi charin eidenai eontas eleutherous, hosoi de êsan xeinoi te kai douloi tôn hepomenôn, en andrapodôn logôi poieumenos eiche. [3.125.4] Polukratês de anakremamenos epetelee pasan tên opsin tês thugatros: elouto men gar hupo tou Dios hokôs huoi, echrieto de hupo tou hêliou, anieis autos ek tou sômatos ikmada.

[3.125.3] Having killed him (in some way not fit to be told), Oroetes then crucified him; as for the Samians in his retinue he let them go, bidding them thank Oroetus for their freedom; and those who were not Samians, or were servants of Polycrates’ followers, he kept for slaves. [3.125.4] So Polycrates was hanged aloft, and thereby his daughter’s dream came true; for he was wahed by Zeus when it rained, and the moisture from his body was his anointment by the sun.[47]

Note that the English translation uses the word “crucified” which is the translation of the Greek word anestaurôse from the verb anastauroô meaning “to impale”. Also notice that the victim Polycrates had already been killed before being crucified.

3.132. [1] τότε δὴ ὁ Δημοκήδης ἐν τοι̂σι Σούσοισι ἐξιησάμενος Δαρει̂ον οἰ̂κόν τε μέγιστον εἰ̂χε καὶ ὁμοτράπεζος βασιλέι ἐγεγόνεε, πλήν τε ἑνὸς του̂ ἐς ̔́Ελληνας ἀπιέναι πάντα τἀ̂λλά οἱ παρη̂ν. [2] καὶ του̂το μὲν τοὺς Αἰγυπτίους ἰητρούς, οἳ βασιλέα πρότερον ἰω̂ντο, μέλλοντας ἀνασκολοπιει̂σθαι ὅτι ὑπὸ ̔́Ελληνος ἰητρου̂ ἑσσώθησαν, τούτους βασιλέα παραιτησάμενος ἐρρύσατο: του̂το δὲ μάντιν ̓Ηλει̂ον Πολυκράτεϊ ἐπισπόμενον καὶ ἀπημελημένον ἐν τοι̂σι ἀνδραπόδοισι ἐρρύσατο. ἠ̂ν δὲ μέγιστον πρη̂γμα Δημοκήδης παρὰ βασιλέι.

[3.132.1] tote dê ho Dêmokêdês en toisi Sousoisi exiêsamenos Dareion oikon te megiston eiche kai homotrapezos basilei egegonee, plên te henos tou es Hellênas apienai panta talla hoi parên. [3.132.2] kai touto men tous Aiguptious iêtrous, hoi basilea proteron iônto, mellontas anaskolopieisthai hoti hupo Hellênos iêtrou hessôthêsan, toutous basilea paraitêsamenos errusato: touto de mantin Êleion Polukrateï epispomenon kai apêmelêmenon en toisi andrapodoisi errusato. ên de megiston prêgma Dêmokêdês para basilei.

[3.132.1] So now having healed Darius at Susa Democedes had a very grand house and ate at the king’s table; all was his, except permission to return to his Greek home. [3.132.2] When the Egyptian chirurgeons who had till now attended on the king were about to be impaled for being less skilful than a Greek, Democedes begged their lives of the king and saved them; and he saved besides an Elean diviner, too, who had been of Polycrates’ retinue and was left neglected among the slaves. Mightily in favour with the king was Democedes.[48]

Again note that the English translation uses the word “impaled” which is the translation of the Greek word anaskolopieisthai from the verb anaskolopizô meaning “to fix on a pole or stake, to impale”.

3.159. [1] Βαβυλὼν μέν νυν οὕτω τὸ δεύτερον αἱρέθη. Δαρει̂ος δὲ ἐπείτε ἐκράτησε τω̂ν Βαβυλωνίων, του̂το μὲν σφέων τὸ τει̂χος περιει̂λε καὶ τὰς πύλας πάσας ἀπέσπασε: τὸ γὰρ πρότερον ἑλὼν Κυ̂ρος τὴν Βαβυλω̂να ἐποίησε τούτων οὐδέτερον: του̂το δὲ ὁ Δαρει̂ος τω̂ν ἀνδρω̂ν τοὺς κορυφαίους μάλιστα ἐς τρισχιλίους ἀνεσκολόπισε, τοι̂σι δὲ λοιποι̂σι Βαβυλωνίοισι ἀπέδωκε τὴν πόλιν οἰκέειν.

[3.159.1] Babulôn men nun houtô to deuteron hairethê. Dareios de epeite ekratêse tôn Babulôniôn, touto men spheôn to teichos perieile kai tas pulas pasas apespase: to gar proteron helôn Kuros tên Babulôna epoiêse toutôn oudeteron: touto de ho Dareios tôn andrôn tous koruphaious malista es trischilious aneskolopise, toisi de loipoisi Babulônioisi apedôke tên polin oikeein.

[3.159.1] Thus was Babylon the second time taken. Having mastered the Babylonians, Darius destroyed their walls and reft away all their gates, neither of which things Cyrus had done at the first taking of Babylon; moreover he impaled about three thousand men that were prominent among them; as for the rest, he gave them back their city to dwell in.[49]

This is Herodotus’ famous account of how Darius I, king of Persia, crucified 3,000 political prisoners. Note that the English translation uses the word “impaled” which is the translation of the Greek word anaskolopise from the verb anaskolopizô meaning “to fix on a pole or stake, to impale”. Herodotus’ account of impaling in ancient Persia is independently confirmed by the famous trilingual Behistun Inscription of Darius.[50]

It is certain that the Assyrians were not the only ones who practiced mutilation and impaling/suspending the bodies of the conquered people [Figure 1 and 2] – even the Persians did the same thing as gathered from the Behistun Inscription.[51] We also find that mutilation preceded impalement in ancient Egypt.

It was noted earlier that Herodotus’ (5th century BCE) writings are used to claim that the earliest references of crucifixion comes from Persia. However, the terminology suggests that the Persians practiced acts of impalement/suspension to execute people without giving too much detail of the actual process. With the testimony of the Behistun Inscription, it is clear that the Persians executed people by impaling them.

Chapman says:

Studies often associate the inception of crucifixion in antiquity with the Persians; and indeed sources frequently testify to acts of suspension under Persian rule. However, it should be noted that:

(1) this testimony is largely found in later Greek and Latin sources (thus stemming from a Hellenistic viewpoint of history),

(2) … the terminology employed by these sources is rarely sufficient in itself definitively to determine that “crucifixion” was employed as opposed some other form of human bodily suspension, and

(3) other ancient people in Europe, Egypt, and Asia were said to crucify as well. Nevertheless, it is apparent from the testimony of the Behistun inscription and elsewhere that Persians frequently employed bodily suspension in the context of execution.[52]

Going further with Herodotus’ account of crucifixion, we read:

9.120 [4] ταυ̂τα ὑπισχόμενος τὸν στρατηγὸν Ξάνθιππον οὐκ ἔπειθε: οἱ γὰρ ̓Ελαιούσιοι τῳ̂ Πρωτεσίλεῳ τιμωρέοντες ἐδέοντό μιν καταχρησθη̂ναι, καὶ αὐτου̂ του̂ στρατηγου̂ ταύτῃ νόος ἔφερε. ἀπαγαγόντες δὲ αὐτὸν ἐς τὴν Ξέρξης ἔζευξε τὸν πόρον, οἳ δὲ λέγουσι ἐπὶ τὸν κολωνὸν τὸν ὑπὲρ Μαδύτου πόλιος, πρὸς σανίδας προσπασσαλεύσαντες ἀνεκρέμασαν: τὸν δὲ παι̂δα ἐν ὀφθαλμοι̂σι του̂ ̓Αρταύ̈κτεω κατέλευσαν.

[9.120.4] tauta hupischomenos ton stratêgon Xanthippon ouk epeithe: hoi gar Elaiousioi tôi Prôtesileôi timôreontes edeonto min katachrêsthênai, kai autou tou stratêgou tautêi noos ephere. apagagontes de auton es tên Xerxês ezeuxe ton poron, hoi de legousi epi ton kolônon ton huper Madutou polios, pros sanidas prospassaleusantes anekremasan: ton de paida en ophthalmoisi tou Artaükteô kateleusan.

[9.120.4] But Xanthippus the general was unmoved by this promise; for the people of Elaeus entreated that Artayctes should be put to death in justice to Protesilaus, and the general himself was so minded. So they carried Artayctes away to the headland where Xerxes had bridged the strait (or, by another story, to the hill above the town of Madytus), and there nailed him to boards and hanged him; and as for his son, they stoned him to death before his father’s eyes.[53]

Note that neither of the two verbs anastauroô or anaskolopizô appear in the only detailed account of crucifixion given by Herodotus in which the victim was “hanged” by being nailed to boards or planks.

There appears to be no word for “crucifixion” as such in Greek. The Greek text of Herodotus speaks of “impalement” which is sometimes translated as crucifixion. Herodotus uses the verbs anaskolopizô and anastauroô both of which mean “to impale”. Generally, he uses the derivatives of the verb anaskolopizô for living persons and anastauroô for corpses.

However, after Herodotus the verbs used to describe the execution in Persia became synonymous to ‘crucify’, in modern literature. As mentioned earlier, the Greek word for “cross” stauros, actually denotes an upright stake or pole. The word crux (cross) is Latin and is also the core of several English words including “crucifixion”.

In many cases, especially during the Roman period, the execution stake became a vertical pole with a horizontal crossbar placed at some point, and although the period of time at which this happened is uncertain, what is known is that this simple impalement later became to be known as crucifixion. Whether the victim was tied, nailed or impaled to the stake, the same Greek words were still used to describe the procedure.

CRUCIFIXION IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

Jewish law requires that a man who has committed a sin worthy of death be impaled on a stake in accordance with the Biblical passage in Deuteronomy 21:22-23.

And if a man have committed a sin worthy of death, and he be put to death, and thou hang him on a tree; his body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but thou shalt surely bury him the same day; for he that is hanged is accursed of God; that thou defile not thy land which Jehovah thy God giveth thee for an inheritance. [Deuteronomy 21:22-23, NIV]

The impression given by these translations is of a person who has been lynched or who is bound by ropes to a tree. This is perhaps incorrect. The Hebrew word talah can have the meaning “to hang” a corpse upon a stake after execution; according to the context, however, it is translated more properly “to crucify” or “to impale” as we find in the Jewish Publication Society’s translation of the Tanakh, i.e., the Hebrew Bible.

If a man is guilty of a capital offense and is put to death, and you impale him on a stake, you must not let his corpse remain on the stake overnight, but must bury him the same day. For an impaled body is an affront to God: you shall not defile the land that the Lord your God is giving you to possess. [Deuteronomy 21:22-23, JPS Tanakh][54]

The key words in Deuteronomy 21:22-23 are talah and ‘ets; and in this verse they refer to a person hanging on a pole or stake as understood from the Gesenius’s Hebrew And Chaldee Lexicon To The Old Testament Scripture.

(a)

(b)

Figure 3: The meaning of (a) talah and (b) ‘ets in the Hebrew Bible.[55]

The fact that a man who has committed a sin worthy of death should be impaled on a stake, is also stated in the Encyclopaedia Judaica:

HANGING is reported in the Bible only as either a mode of execution of non-Jews who presumably acted in accordance with their own laws (e.g., Egyptians: Genesis 40:22; II Sam. 21:6-12: Philistines; and Persians: Esther. 7:9), or as a non-Jewish law imported to or to be applied in Israel (Ezra 6:11), or as an extra-legal or extra-judicial measure (Joshua 8:29).

However, biblical law prescribes hanging after execution: every person found guilty of a capital offense and put to death had to be impaled on a stake (Deuteronomy 21:22); but the body had to be taken down the same day and buried before nightfall, “for an impaled body is an affront to God” (ibid., 23).[56]

It appears that the talmudic and midrashic literature also had a similar understanding of the word talah.[57] Thus, it is not a tree that the criminal is “hanged” upon, but the ‘ets (tree, wood, stake, plank) upon which the criminal is crucified by impalement.

In any case the impaling was not the means used to execute the criminal; he was first put to death by stoning, and his corpse was then exposed as a warning to others. The first mention of impalement in the Bible occurs in Genesis 40:19. The Jewish Publication Society’s translation of the Hebrew text of this verse reads:

In three days Pharaoh will lift off your head and impale you upon a pole; and the birds will pick off your flesh. [Genesis 40:19][58]

This verse suggests that the Israelites first learned of impalement not from the Assyrians but from the Egyptians. The Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (c. 37 – c. 100) reports many incidents of crucifixion in his Antiquities Of The Jews. Josephus uses only (ana)stauroun (the verb stauroun occurs frequently in the New Testament), even in his commentary on the verse Genesis 40:19.

[2.72] καὶ ὁ μὲν ὁμοίαν τὴν πρόρρησιν ἔσεσθαι τῃ̂ του̂ οἰνοχόου προσεδόκα: ὁ δὲ ̓Ιώσηπος συμβαλὼν τῳ̂ λογισμῳ̂ τὸ ὄναρ καὶ πρὸς αὐτὸν εἰπών, ὡς ἐβούλετ’ ἂν ἀγαθω̂ν ἑρμηνευτὴς αὐτῳ̂ γεγονέναι καὶ οὐχ οἵων τὸ ὄναρ αὐτῳ̂ δηλοι̂, λέγει δύο τὰς πάσας ἔτι του̂ ζη̂ν αὐτὸν ἔχειν ἡμέρας: τὰ γὰρ κανα̂ του̂το σημαίνειν: [2.73] τῃ̂ τρίτῃ δ’ αὐτὸν ἀνασταυρωθέντα βορὰν ἔσεσθαι πετεινοι̂ς οὐδὲν ἀμύνειν αὑτῳ̂ δυνάμενον. καὶ δὴ ταυ̂τα τέλος ὅμοιον οἱ̂ς ὁ ̓Ιώσηπος εἰ̂πεν ἀμφοτέροις ἔλαβε: τῃ̂ γὰρ ἡμέρᾳ τῃ̂ προειρημένῃ γενέθλιον τεθυκὼς ὁ βασιλεὺς τὸν μὲν ἐπὶ τω̂ν σιτοποιω̂ν ἀνεσταύρωσε, τὸν δὲ οἰνοχόον τω̂ν δεσμω̂ν ἀπολύσας ἐπὶ τη̂ς αὐτη̂ς ὑπηρεσίας κατέστησεν.

[2.72] kai ho men homoian tên prorrêsin esesthai têi tou oinokhoou prosedoka: ho de Iôsêpos sumbalôn tôi logismôi to onar kai pros auton eipôn, hôs eboulet’ an agathôn hermêneutês autôi gegonenai kai ouch hoiôn to onar autôi dêloi, legei duo tas pasas eti tou zên auton echein hêmeras: ta gar kana touto sêmainein: [2.73] têi tritêi d’ auton anastaurôthenta boran esesthai peteinois ouden amunein hautôi dunamenon. kai dê tauta telos homoion hois ho Iôsêpos eipen amphoterois elabe: têi gar hêmerai têi proeirêmenêi genethlion tethukôs ho basileus ton men epi tôn sitopoiôn anestaurôse, ton de oinochoon tôn desmôn apolusas epi tês autês hupêresias katestêsen.

[2.72] And he expected a prediction like to that of the cupbearer. But Joseph, considering and reasoning about the dream, said to him, that he would willingly be an interpreter of good events to him, and not of such as his dream denounced to him; but he told him that he had only three days in all to live, for that the [three] baskets signify, that on the third day he should be crucified, and devoured by fowls, while he was not able to help himself.

Now both these dreams had the same several events that Joseph foretold they should have, and this to both the parties; for on the third day before mentioned, when the king solemnized his birth-day, he crucified the chief baker, but set the butler free from his bonds, and restored him to his former ministration.[59]

Note that the English translation uses the word “crucified” which is the translation of the words anastaurôthenta and anestaurôse from the Greek anastauroô meaning “to impale”. The Smith’s Bible Dictionary also observes that the hangings reported in Genesis 40:19 refer to crucifixion.

Crucifixion was in use among the Egyptians, (Genesis 40:19); the Carthaginians, the Persians, (Esther 7:10); the Assyrians, Scythains, Indians, Germans, and from the earliest times among the Greeks and Romans. Whether this mode of execution was known to the ancient Jews is a matter of dispute. Probably the Jews borrowed it from the Romans. It was unanimously considered the most horrible form of death.[60]

Similarly, the Encyclopaedia Judaica says that:

There are reports of crucifixions from Assyrian, Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Punic, and Roman sources.[61]

Given these facts, it is strange that the Christian missionaries have claimed that crucifixion was not known in Egypt during the time of either Joseph and Moses even though the Judeo-Christian scholars have pointed to its existence in ancient Egypt. Let us now turn our attention to the evidence of crucifixion from ancient Egypt.

5. Crucifixion In Ancient Egypt

According to the Christian missionaries, their evidence that the Qur’an is in error when it mentions crucifixion in Egypt is based on “archaeology and history”. If one reads their material, it is neither based on any archaeological evidence nor any historical investigation! Another example of the missionary’s unparalleled arrogance about the historical investigation on this issue can be seen here and here. So much for their “crucifiction” theories!

Rather ironically, the missionaries have even managed to misrepresent the evidence used to forward their own “facts”. The missionaries, referring to the famous Encyclopaedia Britannica, proclaimed they were providing “one authoritative reference”:

Crucifixion, an important method of capital punishment, particularly among the Persians, Seleucids, Jews, Carthaginians, and Romans [was practiced] from about the 6th century BC to the 4th century AD. Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, abolished it in the Roman Empire in AD 337, out of veneration for Jesus Christ, the most famous victim of crucifixion. … [The earliest recording of a crucifixion was] in 519 BC [when] Darius I, king of Persia, crucified 3,000 political opponents in Babylon.

By the use of [] brackets, the missionaries hoped to convey that the first recorded incidence of crucifixion was in 519 BCE during the reign of Darius I, King of Persia. All they managed to convey however was their own distortion of source material. Let us see what Encyclopedia Britannica actually says:

an important method of capital punishment, particularly among the Persians, Seleucids, Carthaginians, and Romans from about the 6th century BC to the 4th century AD. Constantine the Great, the first Christian emperor, abolished it in the Roman Empire in AD 337, out of veneration for Jesus Christ, the most famous victim of crucifixion. … In 519 BC Darius I, king of Persia, crucified 3,000 political opponents in Babylon.[62]

So this “one authoritative reference” championed by the missionaries turns out to be a reference to their own misunderstanding and distortion. Now that it is abundantly clear that Encyclopaedia Britannica does not provide information in relation to the first recorded instances of crucifixion in world history, let us now deal with the issue of crucifixion in ancient Egypt using the information obtained from Egyptology.

HIEROGLYPH FOR CRUCIFYING OR IMPALING A PERSON UPON A STAKE

The first thing to establish is whether there exists any hieroglyph that mentions impaling people on stakes. The best place to start is Die Sprache Der Pharaonen Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch, a concise Egyptian-German dictionary. The hieroglyph depicting impalement on a stake is shown below.[63]

Figure 4: Hieroglyph writing for “Stake. rdj hr = To put on the stake (for punishment)”; det. = determinative, hieroglyph for classifying Egyptian words. Here it shows an impaled man bent upon a stake.[64]

A recent edition of Die Sprache Der Pharaonen Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch gives even more information on the hieroglyphs showing impalement as seen below.[65]

Figure 5: Hieroglyph writing for Pfahl, i.e., “Stake”. The interesting ones of 2, 3, 5, and 6. Also see “Pfählen”.

This is the clearest example that people in ancient Egypt were crucified by impalement on stakes. What about the times in which this punishment was imposed in ancient Egypt?

EVIDENCE OF IMPALEMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT

In order to analyze and interpret the evidence of crucifixion by impaling people on a stake in Egypt, we present a simplified chronology of ancient Egyptian history containing royal names associated with the period for easy reference. Unless otherwise stated, specific dates for particular Dynasties and Kings that we quote within this paper are taken from Nicolas Grimal’s book, A History of Ancient Egypt.[66] Please note that the exact Egyptian chronologies are slightly uncertain, and all dates are approximate. The reader will find slightly different schemes used in different books.

| Dynasties | Dates BCE (approx.) | Period | Some Royal Names Associated with Period |

| 1 & 2 | c. 3150 – 2700 | Thinite Period | Narmer-Menes, Aha, Djer, Hetepsekhemwy, Peribsen |

| 3 – 6 | c. 2700 – 2190 | Old Kingdom | Djoser, Snofru, Khufu (Cheops), Khafre (Chephren), Menkauhor, Teti, Pepy. |

| 7 – 11 | c. 2200 – 2040 | First Intermediate | Neferkare, Mentuhotpe, Inyotef |

| 11 & 12 | c. 2040 – 1674 | Middle Kingdom | Ammenemes, Sesostris, Dedumesiu |

| 13 – 17 | c. 1674 – 1553 | Second Intermediate | Sobekhotep II, Chendjer, Salitis, Yaqub-Har, Kamose, Seqenenre, Apophis. Hyksos formed 15th and 16th Dynasties |

| 18 – 20 | c. 1552 – 1069 | New Kingdom | Ahmose, Amenhotep (Amenophis), Hatshepsut, Akhenaten (Amenophis IV), Horemheb, Seti (Sethos), Ramesses II, Merenptah |

Table I: Chronology of the Egyptians Dynasties

Keeping this in mind, let us now look at the evidence of crucifixion by impaling people on a stake in ancient Egypt. The evidence is arranged in chronological order.

A. Theban Account Papyrus (Papyrus Boulaq 18)

Papyrus Boulaq 18 is dated to the early Second Intermediate Period reign of Chendjer / Sobekhotep II; both of them kings from the 13th Dynasty. The account in Papyrus Boulaq is given below.[67]

Figure 6: Mentioning of impalement in the Theban account papyrus (Papyrus Boulaq 18).

a blood bath (?) had occurred with (by?) wood (?) … the comrade was put on the stake, land near the island …; waking alive at the places of life, safety and health …

B. Stela Of Amenophis IV (Akhenaten)

Amenophis IV or Akhenaten was known as the Heretic King. He was the tenth king of the 18th Dynasty in the New Kingdom Period. Following is an interesting stela showing the Nubian prisoners of war being impaled.

Figure 7: Excerpts from the Stela of Amenophis IV, showing impalement of Nubian prisoners of war.

List (of the enemy belonging to) Ikayta: living Nehesi 80+ ?; … | … their (chiefs?) 12; total number of live captives 145; those who were impaled … | … total 225; beasts 361.[68]

Interestingly, The New International Dictionary Of The Bible says:

Crucifixion was one of the most cruel and barbarous forms of death known to man. It was practiced, especially in the times of war, by the Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Egyptians, and later by the Romans. So dreaded was it that even in the pre-Christian era, the cares and troubles of the life were often compared to a cross.[69]

C. Abydos Decree Of Sethos I At Nauri, Year 4.

Sethos I belonged to the 19th Dynasty in the New Kingdom Period. His rule preceded the rule of Ramesses II. Below is his interesting decree at Nauri.

Figure 8: Excerpts from the Abydos Decree of Sethos I at Nauri, Year 4.

… Now as for any superintendent of cattle, any superintendent of donkeys, any herdsman belonging to the Temple of Menmare Happy in Abydos, who shall sell of any beast belonging to the Temple of Menmare Happy in Abydos to someone else; likewise whoever may cause it to be offered on some other document, and it not be offered to Osiris his master in the Temple of Menmare Happy in Abydos; the law shall be executed against him, by condemning him, impaled on the stake, along with forfeiting(?) his wife, his children and all his property to the Temple of Menmare Happy in Abydos, …[70]

D. Amada Stela Of Merenptah: Libyan War (Karnak)

Merenptah, son of Ramesses II, defeated the threat posed by the Libyans. He belonged to the 19th Dynasty in the New Kingdom Period. Here the prisoners were impaled on the stake on the South of Memphis.

Figure 9: Excerpts from the Amada Stela of Merenptah; Libyan War (Karnak).

… Never shall they leave any people for the Libu (i.e., Libyans), any who shall bring them up in their land! They are cast to the ground, (?) by hundred-thousands and ten thousands, the remainder being impaled (‘put to the stake’) on the South of Memphis. All their property was plundered, being brough back to Egypt…[71]

E. The Abbott Papyrus

This is an account of the Great Tomb Robberies of the 20th Dynasty in the New Kingdom Period. Notice that the oath includes mutilation before the actual impalement.

Figure 10: Excerpts from the Abbott Papyrus that deals with the oath on pain of mutilation and impalement.

… The notables caused this coppersmith to be examined in most severe examination in the Great Valley, but it could not be found that he knew of any place there save the two places he had pointed out. He took an oath on pain of being beaten, of having his nose and ears cut off, and of being impaled, saying I know of no place here among these tombs except this tomb which is open and this house which I pointed to you…[72]

F. Papyrus BM10052

This is an account of the Great Tomb Robberies of the 20th Dynasty in the New Kingdom Period. Notice that the oath includes mutilation before the actual impalement.

Figure 11: Excerpts from Papyrus BM10052.

The scribe Paoemtaumt was brought. he was given the oath not to speak falsehood. He said, As Amun lives and as the Ruler lives, if I be found to have had anything to do with any one of the thieves may I be mutilated in nose and ears and placed on the stake. He was examined with the stick. He was found to have been arrested on account of the measurer Paoemtaumt son of Kaka.[73]

These hieroglyphs are by no means the only ones. There exist others from the New Kingdom Period showing impalements.[74]

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT

Ancient Egypt was known for some of the worst kinds of capital punishments. The ancient Egyptians understood the necessary deterrent that these punishments provided. It appears that punishment in ancient Egypt became more severe with the times, especially with the advent of the New Kingdom Period.

The punishments in the New Kingdom Period were very brutal and included beatings, mutilation, impalement, and being treated as a slave. The Lexikon Der Ägyptologie – an encyclopaedia of Egyptology, gives a brief overview of the different forms of punishment in Egypt under the heading “Strafen” (i.e., punishment / penalties). It says:

Decrees and trial documents, in the latter particularly from oath formulas, have given us the following judicial punishments. Physical punishments, as the most severe for capital crimes … the death penalty by impaling, burning, drowning, beheading or being eating by wild animals. Only the King or the Vizier had the right to impose such punishment. High ranking personalities were granted by the King to commit suicide.

Physical punishments were also mutilation punishments by cutting off hands, tongue, nose and or ears, castration as well as beatings in the form of 100 or 200 strokes, often with 5 bleeding wounds, occasionally with 10 burn marks. Sometimes also the part of the body, e.g. the soles of the feet, which had to be beaten.

Frequently there were prison sentences in addition to physical punishments, such as exile to Kusch, to the Great Oasis or to Sile, with the obligation of forced labour as mine worker or stone mason as well as loss of assets. Women were banished to live in the outbuildings at the back of the house. Prison sentences as we know them were unknown. There were just remand prison for the accused and witnesses for serious crimes before and during the trial. Abuse of office was punished by loss of office and transfer to manual work.[75]

Similarly Lurje in his Studien Zum Altägyptischen Recht (Studies In The Ancient Egyptian Law) states:

Among others we find mutilation, mutilation and deportation to forced labour in Ethiopia, just deportation to forced labour in Ethiopia, impaling (tp-ht), punishment in form of 100 beatings and adding 50 wounds, punishment in form of 100 beatings and withdrawal of part or all of the disputed assets, punishment in form of 100 beatings and payment of twice the value of the matter in dispute, asset liability, cutting off of the tongue, loss of rank and transfer to the working class, handing over to be eaten by the crocodile and finally living in the outbuildings of the house.[76]

It is clear that one of the severest penalties in ancient Egypt included mutilation and mutilation followed by impalement, especially in the New Kingdom Period. The mutilation includes cutting off hands, tongue, nose and ears or even castration. Harsh penalties such as crucifixion by impalement would be imposed only by either the King or the Vizier.

John Wilson had discussed the authority of the King or the Vizier to impose punishments which the interested readers might find useful.[77] Thus the Qur’anic address of referring to Pharaoh as “Lord of Stakes” certainly fits very well with the available evidence. It also adds irony due to the fact that even though the Pharaoh claimed to be god, the greatest act of his lordship was confined to killing people by putting them on the stake.

When did Joseph and Moses enter Egypt? As far as the missionaries are concerned, they had claimed the dating provided by them is “conservative”.

We have, however, no record that Egyptians used crucifixion as punishment in the time of Moses (1450 BC, conservative date; 1200 BC at the latest) or even Joseph (1880 BC, conservative date).

The “conservative” dating of the missionaries correspond quite closely with the New Chronology proposed by David Rohl in his book A Test of Time.[78] This is the revisionist dating not the “conservative” dating. Fortunately, we have A Waste of Time homepage on the internet that includes a collection of articles written by scholars of Egyptology such as Professor Kenneth Kitchen as well as amateurs refuting many of the claims of Rohl. Even the evangelical Christians do not take Rohls’ work seriously. We wonder why the missionaries insist on using such discredited scholarship to advance their fictitious arguments.

The majority of scholars say that Joseph entered Egypt during the time of the Hyksos. The Hyksos belonged to a group of mixed Semitic-Asiatics who infiltrated Egypt during the Middle Kingdom and became rulers of Lower Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period. They formed the 15th and 16th Dynasties. The generally accepted theory by biblical scholars appears to be that Moses lived during the reign of at least two kings, Rameses II and his successor Merneptah in the New Kingdom Period.

Let us now gather the evidence that we have acquired so far about crucifixion in Egypt. Table II shows the ruler of Egypt when people were crucified by impalement on stakes as well as the time when Joseph and Moses entered Egypt.

| Dynasties | Dates BCE (approx.) | Period | Ruler When Crucifixion Happened | Prophet |

| 3 – 6 | c. 2700 – 2200 | Old Kingdom | ||

| 7 – 11 | c. 2200 – 2040 | First Intermediate | ||

| 11 & 12 | c. 2040 – 1674 | Middle Kingdom | ||

| 13 – 17 | c. 1674 – 1553 | Second Intermediate | Sobekhotep II, Chendjer (13th Dynasty). Hyksos formed 15th and 16th Dynasties | Joseph |

| 18 – 20 | c. 1552 – 1069 | New Kingdom | Akhenaten (Amenophis IV), Ramesses, Merenptah | Moses |

Table II: This Table provides information about the ruler of Egypt when people were crucified by impalement on stakes and the time when Joseph and Moses entered Egypt.

What is interesting to note is that the earliest available evidence of the occurrence of crucifixion in ancient Egypt is seen in Papyrus Boulaq 18 from the time of Sobekhotep II / Chendjer of the 13th Dynasty in the Second Intermediate Period. Joseph, according to majority of scholars, entered Egypt during the rule of the Hyksos who formed the 15th and 16th Dynasties in the Second Intermediate Period. This means that crucifixion happened in Egypt even before Joseph entered Egypt.

Crucifixion also happened before Moses came to Egypt, during the Amenophis IV (Akhenaten). It also happened after the event of Exodus as seen in the papyri related to the Great Tomb Robberies of the 20th Dynasty. This completely refutes the claim of the Christian missionaries that the mention of crucifixion in the Qur’an during the time of Joseph and Moses is historically inaccurate.

6. Conclusions

Contrary to the missionaries’ own imaginative definition, crucifixion, as attested in a variety of sources, can be understood as the act of affixing by nailing, binding or impaling a living victim or sometimes a dead person to a cross, stake or tree, whether for executing the body or for exposing the corpse.

However, all attempts to give a perfect description of the crucifixion in archaeological terms are in vain as there were just too many different possibilities depending upon the whim of the executioner. The “cross” was originally a single upright stake or post upon which the victim was either tied, nailed or impaled as seen in the ancient references to crucifixion.

Accordingly, as we have demonstrated, it would not only be inappropriate but also historically inaccurate to restrict our understanding of the scope and application of crucifixion as it was practiced during Roman times, especially throughout the early Christian period. The mention of crucifixion in the Qur’an comes from the root Ṣ-L-B and it has no connotations of a cross or its shape.

Rather it indicates any method of execution which makes the body stiffened or hardened (as any movement would cause excruciating pain) and results in leaking of bodily fluids. Therefore, crucifixion by impalement and other forms of crucifixion are included here without making any distinction between them.

With regard to ancient Egyptian history, we can observe a progression in the ‘cruelty’ of punishments with time, acutely so during the New Kingdom period (c. 1552 – c. 1069 BCE). Without delving into the intricacies of ancient Egyptian criminal law, we can undoubtedly observe that one method of punishment was crucifying people by impalement.

The earliest extant evidence for this severe form of punishment is found during the reign of Sobekhotep II / Chendjer in the Second Intermediate period (c. 1674 – c. 1553 BCE), as indicated by the Papyrus Boulaq 18. Moving forward to the New Kingdom period (c. 1552 – c. 1069 BCE), we have numerous papyri, including the Abbot Papyrus and Papyrus BM10052, as well as numerous stele including the Stela of Amenophis IV, Abydos Decree of Sethos I at Nauri and Amada Stela of Merenptah, indicating the punishment of crucifixion by impalement.

These dates correspond well with the dates the majority of scholars attribute to Joseph and Moses entry into Egypt. Therefore, based on this historical appreciation of ancient Egyptian history, crucifixion, as evidenced in a variety of hieroglyph papyri manuscripts and stela, was practiced as impalement, and, this form of punishment was already well established by the time Joseph entered Egypt. In sum, the story as narrated in the Qur’an correlates very well with the available evidence.

Equipped with an academically accepted chronology of ancient Egyptian history and an accurate historical understanding of what the words ‘cross’ and ‘crucifixion’ actually mean, once again, we find the missionaries making unsubstantiated claims.[79] Their “facts” are based on unproven ancient Egyptian chronologies that have received scathing reviews from fellow academics not to mention their own theologians.

Combined with a superficial understanding regarding the concepts of “cross” and “crucifixion”, and how this form of punishment was expressed by different cultures and civilisations (both ancient and modern), the missionaries struggle to form any type of cogent argumentation and instead distort source material and make extensive use of soundbites. In fact, the only thing in error here is the missionaries’ “research methodology”, which, in this particular instance, can properly be characterised as lightweight and schizophrenic.

Perhaps it is best to conclude with H.S. Smith’s observation in his book The Fortress Of Buhen: The Inscriptions:

… I think the sense of nty hr htw ‘those who are on the stakes’ cannot be mistaken; the evidence for the Egyptians impaling their enemies is far too strong to be doubted.[80]

And Allah knows best!

References:

The World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviors

The “Crucifixion” Of Jesus Christ A Borrowed Ancient Myth

Who was Crucified on the Cross, what for and who for?

Does the Noble Quran (19:33) confirm Jesus’ crucifixion?

Did Allah deceive Christians by allowing a substitute person on the Cross?

Does Psalm 2:7 refer to Jesus or King David?

Was Jesus Sent to be Crucified?

The Resurrection Hoax, a Big Scam

Contradictions in the Resurrection of Jesus Accounts

𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐛𝐥𝐞𝐦𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐓𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐥(𝐬) & 𝐂𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐱𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐨𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐥𝐬

The Resurrection Hoax of Prophet Jesus!

A List of Biblical Contradictions

Mankind’s corruption of the Bible

Contradictions everywhere in the Bible

Paul The False Apostle of Satan

The Problem of the Bible: Inaccuracies, contradictions, fallacies, scientific issues and more.

Qur’anic Accuracy Vs. Biblical Error: The Kings and Pharaohs Of Egypt

The Resurrection Hoax, a Big Scam

Top 20 Most Damning Bible Contradictions

Christianity Contradicts the Bible!

Deconstructing Isaiah 53 And The Crucifixion / Resurrection Of Jesus

The lie of the crucifixion of Jesus!

Top 100 Reasons Jesus Was Never Crucified And Never Killed!!!

Early Christians Rejected Trinity

References & Notes

[1] E. W. Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, 1968, Part – 4, Librairie Du Liban: Beirut, pp. 1711-1713, especially p. 1711.

[2] J. M. Cowan (Ed.), Hans – Wehr Dictionary Of Modern Written Arabic, 1980 (Reprint), Librairie Du Liban: Beirut, p. 521. For the dictionaries dealing with the use of Ṣ-L-B in the Qur’an see E. M. Badawi & M. Abdel Haleem, Arabic-English Dictionary Of Qur’anic Usage, 2008, Brill: Leiden, pp. 530-531; A. A. Ambros (Collab. S. Procházka), A Concise Dictionary Of Koranic Arabic, 2004, Reichert Verlag Wiesbaden (Germany), p. 162; A. A. Nadwi, Vocabulary Of The Holy Qur’an, 1986, Iqra International Education Foundation: Chicago (IL), p. 336.

[3] A. Jeffery, The Foreign Vocabulary Of The Qur’an, 1938, Gaekwad’s Oriental Series: No. LXXIX, Oriental Institute: Baroda (India), p. 197.

[4] D. W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish And Christian Perceptions Of Crucifixion, 2008, Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen (Germany), p. 32. Such usage is also to be found in J. M. Ford, “The Crucifixion Of Women In Antiquity”, Journal Of Higher Criticism, 1996, Volume 3, No. 2, pp. 292-294.

[5] D. W. Chapman, Ancient Jewish And Christian Perceptions Of Crucifixion, 2008, op. cit., p. 32. Chapman’s book is not a history of the application of crucifixion in the ancient world rather his focus is on the perceptions of crucifixion [ibid., p. 2]. Nevertheless, Chapman provides an informative detailed study on crucifixion terminology spanning numerous different languages [ibid., pp. 7-33]. See especially his six point summary on crucifixion terminology and suspension [ibid., pp. 30-33].

[6] H. G. Liddell, R. Scott, H. S. Jones & R. McKenzie, A Greek-English Lexicon, 1966, A New Edition (Ninth Edition) Revised And Augmented Throughout, Volume II, At The Clarendon Press: Oxford, p. 1635.

[7] W. Bauer, F. W. Danker, W. F. Arndt & F. W. Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament And Other Early Christian Literature, 2000, Third Edition, University of Chicago Press: London & Chicago, p. 941.

[8] W. D. Mounce, The Analytical Lexicon To The Greek New Testament, 1993, Zondervan Publishing House: Grand Rapids (MI), p. 422.

[9] J. P. Louw & E. A. Nida, Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament: Based On Semantic Domains, 1998/9, Volume I, United Bible Societies: New York, pp. 56-57.

[10] T. Friberg, B. Friberg & N. F. Miller, Analytical Lexicon Of The Greek New Testament, 2000, Baker Books: Grand Rapids (MI), p. 355.

[11] H. Balz & G. Schneider (Eds.), Exegetical Dictionary Of The New Testament, 1993, Volume 3, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, p. 268.

[12] “Cross”, in H. Lockyer, Sr. (General Editor), F. F. Bruce et al., (Consulting Editors), Nelson’s Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 1986, Thomas Nelson Publishers, p. 265.

[13] “Cross, Crucify”, Vine’s Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words, Click here.

[14] “Cross”, in J. Hastings et al. (Eds.), A Dictionary of Bible, Dealing With Its Language, Literature And Contents, Including The Biblical Theology, 1898, Volume I, T. & T. Clarke: Edinburgh, p. 528.

[15] “Crucifixion”, in J. Hastings (Revised by Frederick C. Grant and H. H. Rowley), Dictionary Of The Bible, 1963, 2nd Edition, T. & T. Clarke: Edinburgh, p. 193. For a similar explanation of the Greek word stauros see J. H. Thayer, Thayer’s Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament Coded With Strong’s Concordance Numbers, 2005 (7th Printing), Hendrickson Publishers Inc.: Peabody (MA), p. 586.

[16] “Cross, Crucifixion”, J. D. Douglas (Organizing Editor), The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 1980, Inter-Varsity Press: Leicester (England), p. 342.

[17] Only the cross-beam was actually carried to the site of the execution, not the entire cross: “..after being whipped, or ‘scourged,’ dragged the crossbeam of his cross to the place of punishment, where the upright shaft was already fixed in the ground.” Encyclopaedia Britannica.

[18] “Crucifixion” in G. A. Buttrick (Ed.), The Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The Bible, 1962, Volume I, Abingdon Press: Nashville (TN), p. 746.

[19] H. G. Liddell, R. Scott, H. S. Jones & R. McKenzie, A Greek-English Lexicon, 1966, A New Edition (Ninth Edition) Revised And Augmented Throughout, Volume II, op. cit., p. 1635.

[20] W. Bauer, F. W. Danker, W. F. Arndt & F. W. Gingrich, A Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament And Other Early Christian Literature, 2000, Third Edition, op. cit., p. 941.

[21] W. D. Mounce, The Analytical Lexicon To The Greek New Testament, 1993, op. cit., p. 422.

[22] J. P. Louw & E. A. Nida, Greek-English Lexicon Of The New Testament: Based On Semantic Domains, 1998/9, Volume I, op. cit., p. 237.

[23] T. Friberg, B. Friberg & N. F. Miller, Analytical Lexicon Of The Greek New Testament, 2000, op. cit., p. 355.

[24] “Crucifixion”, in B. M. Metzger and M. D. Coogan (Eds.), Oxford Companion To The Bible, 1993, Oxford University Press: Oxford & New York, p. 141.

[25] G. G. O’Collins, “Crucifixion” in D. N. Freedman (Editor-in-Chief), Anchor Bible Dictionary, 1992, Volume I, Doubleday: New York, p. 1207.

[26] “Crucifixion”, New Catholic Encyclopaedia, 1981, Volume IV, The Catholic University of America: Washington, p. 485.

[27] “Crucifixion Of Christ”, in H. Lockyer, Sr. (General Editor), F. F. Bruce et al., (Consulting Editors), Nelson’s Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 1986, op. cit., p. 267.

[28] “Cross, Crucifixion”, J. D. Douglas (Organizing Editor), The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 1980, op. cit., p. 342.