Pharaoh And His Gods In Ancient Egypt

Mohamad Mostafa Nassar

Twitter:@NassarMohamadMR

Quran Corrects The Corrupted Bible on Historical Matters

1. Introduction

Concerning the ancient Egyptian religion during the time of the Pharaohs, the Qur’an reports three interesting statements. Firstly, when Prophet Moses calls Pharaoh to worship one true God, the call is rejected. Instead Pharaoh collects his men and proclaims that he is their Lord, most high.

Has the story of Moses reached thee? Behold, thy Lord did call to him in the sacred valley of Tuwa, “Go thou to Pharaoh for he has indeed transgressed all bounds: And say to him, ‘Wouldst thou that thou shouldst be purified (from sin)? – And that I guide thee to thy Lord, so thou shouldst fear Him?'” Then did (Moses) show him the Great Sign. But (Pharaoh) rejected it and disobeyed (guidance); Further, he turned his back, striving hard (against God). Then he collected (his men) and made a proclamation, Saying, “I am your Lord, Most High”. [Qur’an 79:15-24]

Secondly, when Moses goes to Pharaoh with clear signs, they are rejected as being “fake”. Pharaoh then addresses his chiefs by saying that he knows of no god for them except him.

Pharaoh said: “O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself… [Qur’an 28:38]

The last statement comes in connection with the victory of Prophet Moses over the magicians of Egypt. Here the chiefs of Pharaoh say to him that this victory of Moses over the magicians could result in an abandonment of you (i.e., Pharaoh) and your gods (Arabic: wa yadaraka wa ālihataka) in favour of the God of Moses.

And the chiefs of Pharaoh’s people said: “Do you leave Musa and his people to make mischief in the land and to forsake you and your gods?” He said: “We will slay their sons and spare their women, and surely we are masters over them.” [Qur’an 7:127]

Thus the Qur’an reports three important statements concerning the ancient Egyptian religion as practiced during the time of Moses. Firstly, Pharaoh’s proclamation that he is their Lord, Most High. Secondly, Pharaoh’s claim that he knew of no god for their chiefs except him. Thirdly, concerning other gods in Egypt who were Pharaoh’s gods. In other words, a distinction is made between Pharaoh and his gods.

However, according to Christian missionaries, the statement reported in the Qur’an 28:38 is in “direct contradiction” to Qur’an 7:127.

In other words, the Pharaoh claims that he is the only god for his people, the Egyptians, in direct contradiction to 7:127 where the chiefs of his people express concern that Moses’ victory could lead to the downfall of their traditional Egyptian gods (in the plural).

Commenting on the Qur’an 28:38, another Christian missionary says:

This is an enormous historical error. The Pharaohs believed themselves divine, however there is no evidence that any Pharaoh considered himself the one and only god. Amenhotep is considered to be a monotheist, however he did not hold himself to be the one and only god, he believed that title belonged to the god Aten [also called Aton]. The god Ra was considered the highest god in ancient Egypt, not the Pharaoh.

In order to support their claim of “direct contradiction”, they quote Muhammad Asad, a well-known Qur’an translator, who considers that the Qur’an 28:38 should not be “taken literally” as the Egyptians also worshipped many gods.[1] Given the fact that Asad is better known for his translation of the Qur’an rather than his scholarship in the religion of ancient Egypt, the missionaries then go on to explain the alleged “discrepancy” without any recourse to reliable, verifiable historical sources. As one navigates the jumbled maze of verbiage one encounters apparently innocuous questions such as:

Did the Egyptians have many gods or only one god? Since this may not have been the same at all times, we would have to ask more specifically: What was the religion of the Egyptians at the time of the Exodus?

As is so often the case, the Christian missionaries fail to provide a single footnote or reference to substantiate their reconstruction of the ancient Egyptian religion. Instead the reader is treated to a tour de force of over a dozen links to internet websites of varying degrees of usefulness including a webpage belonging to the BBC, an Egyptian tourism website, a webpage belonging to the Edkins family that is “designed for children aged 7-11 years old” and a webpage authored by a public school teacher in Ohio. Ironically, the last link provided by them has an advertisement on the homepage offering a graduate degree in history.

Regrettably, what is sorely missing is an evaluation of the statements made in the Qur’an in light of the nature of religion in ancient Egypt. Who was Pharaoh and was he considered divine, human or both? What was his relationship with other gods of Egypt? Whom did the Egyptians consider as their principal god?

In order to answer questions like these, we will examine a selection of primary and secondary sources. However, at the outset, it must be said that since the setting of the story of Moses in both the Qur’an and in the Bible is in the New Kingdom Period, more specifically, according to majority of the biblical scholars, during the time of Ramesses II or Merneptah, all our examples of the nature of ancient Egyptian religion would come from this period.

2. Pharaoh As Lord & God

As noted earlier, the Qur’an reports the belief of the chiefs who made a distinction between Pharaoh – who claimed to be the god of Egypt – and his gods. In order to understand this distinction, let us dwell briefly into the nature of ancient Egyptian religion. We will only provide a general description here and readers may refer to the cited works.

It is well-known that the Pharaohs have often been characterized as gods on earth. While the kingship as an institution may have continued fairly constantly throughout more than 3,000 years of history of ancient Egypt, just what the office signified, how the kings understood their role, and how the general populace perceived the king do not constitute a uniform concept that span the centuries without change.

In other words, the ancient Egyptians’ view of the king, implied by various historical references, was not static. It underwent changes during the more than 3,000 years of Egyptian history.[2] From the early times the epithet nṭr referred directly to the king as a god. Sometimes the term occurred alone and at other times it appeared with a modifying or descriptive word.[3]

Tradition says that in the beginning, kingship came to the earth in the person of the god-king, Rēʿ,, who brought his daughter, Maat, the embodiment of Truth and Justice, with him.[4] Therefore, the beginning of the earth was simultaneous with the beginning of kingship and social order. The king, therefore, ruled by divine right, his office having come into existence at the time of the creation itself.

The kings of Egypt legitimised their claim to the throne in ways that were influenced by religious beliefs. The god-king, Horus, was the son of Osiris who had been king; and so every new king of Egypt became Horus to his predecessor’s Osiris. By acting as Horus had towards Osiris, in other words, by burying his predecessor, each new king made legal claim to the throne.

The divinity was only acquired through the rites of ascension to the throne of Egypt. The device of theogamy was used for this purpose. Here, the principal god of the time was said to have assumed the form of the reigning king in order to beget a child on his queen: that child later claimed to be the offspring of both his earthly and heavenly father; and the earthly father was quite content to be cuckolded by the god.

Ancient Egyptians were aware of their monarch’s inherent mortality. The unavoidable question now arises: How could they rationalize this apparent human/divine dichotomy of their rulers? It could be that it was not a conflict for them. The king seemed to possess aspects of human at some times and of the divine at others. The Egyptians knew that he originated in the world of humans, but he could function in both worlds.

A ruler envisioned as both human and divine was best suited to intercede between the human and divine worlds. Not surprisingly, due to this perceived fluidity of the human and divine components of the king’s nature, it was not difficult for Egyptians to develop variations on and additions to their concept of kingship.

The king’s human/divine dichotomy was, surprisingly, a unifying factor in Egyptian religious life. In theory, he was chief priest in every temple; the only person entitled to officiate in the temple rituals, the only person entitled to enter the holy of holies within the temple. Obviously, this was evident: the king could not be in every temple at once.

However, the fiction was always maintained in the reliefs carved on the walls of temples, which always show the king making offerings to the gods. He was the embodiment of the connection between the world of men and the world of gods, the lynchpin of Egyptian society.

It was his task to make the world go on functioning; it was his task to make the sun rise and set, the Nile to flood and ebb, the grain to grow: all of which could only be achieved by the performance of the proper rituals within the temples. With the advent of the New Kingdom Period, the religion in ancient Egypt also began to change. Deification of the Pharaohs started to become a norm.

By the early New Kingdom, deification of the living king had become an established practice, and the living king could himself be worshipped and supplicated for aid as a god.[5]

During the time of Ramesses II, the deification of Pharaoh reached its peak as evidenced in numerous cult statues as well as supporting hieroglyphs and papyri.[6] Keeping this in mind, let us now look at the two statements made in the Qur’an, i.e., Pharaoh – the god of Egypt – and his gods.

PHARAOH AS GOD – THE VIEW OF THE KING’S SUBJECTS

God says in the Qur’an that Pharaoh addressed his chiefs by saying that he knows for them of no god but himself [Qur’an 28:38]. This statement can be verified by simply checking the views of the king’s subjects, i.e., court officials and the common folk.

What the subjects of the Pharaoh could expect of the ruler in accordance with the Egyptian theory of the kingship is very well summed up in a quotation from the tomb autobiography of the famous vizier Rekhmereʿ of Tuthmosis III from 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period. The inscription occupies the southern end-wall of the tomb of Rekhmereʿ and comprises of 45 lines of hieroglyphs painted in green upon a plaster surface.

Rekhmerēʿ’s relation to the king (II. 16-19)

… What is the king of Upper Egypt? What is the king of Lower Egypt? He is a god by whose dealings one lives. [He is] the father and mother [of all men]; alone by himself, without an equal …[7]

According to Rekhmereʿ, the king of Egypt was a god by whose decree one lives. He is alone, has no equal and takes care of his subjects like a parent. This affirms that the officials in ancient Egypt considered Pharaoh to be their principal god, thus indirectly confirming the statement made by Pharaoh to his chiefs, as reported in the Qur’an, that he knew of no god for them but himself. Furthermore, Rekhmereʿ adds that the ruler like Egypt had divine qualities such as omniscience and a wonderful creator.

The audience with Pharaoh (II. 8-10)

…. Lo, His Majesty knows what happens; there is indeed nothing of which he is ignorant. (9) He is Thoth in every regard. There is no matter which he has failed to discern…… [he is acquainted] with it after the fashion of the Majesty of Seshat (the goddess of writing). He changes the design into its execution like a god who ordains and performs…..[8]

Furthermore, the king was recognized as the successor of the sun-god Rēʿ, and this view was so prevalent that comparisons between the sun and king unavoidably possessed theological overtones. The king’s accession was timed for sunrise. Hence the vizier Rekhmereʿ explained the closeness of his association with the king in the following words:

Rekhmerēʿ’s as a loyal defender of the king (II. 13-14)

… I [saw] his person in his (real) form, Rēʿ the lord of heaven, the king of the two lands when he rises, the solar disk when he shows himself, at whose places are [Black] Land and Red Land, their chieftains inclining themselves to him, all Egyptians, all men of family, all the common fold…… ….. lassoing him who attacks him or disputing with him…[9]

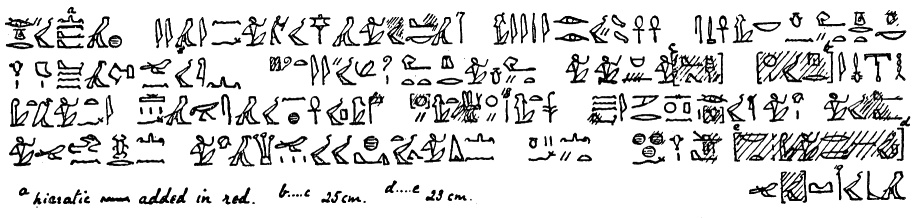

Rekhmereʿ also adds that the whole of Egypt followed the ruler of Egypt, whether chieftains or common folk. Now what about the views of the common folk concerning the divine nature of the king? For this let us turn our attention to Papyrus Anastasi II dated to the time of Merneptah, successor of Ramesses II.[10] Papyrus Anastasi II begins by “Praise of the Delta Residence” of the Ramesside kings. The textual content of this section is similar to that of Papyrus Anastasi IV, (6,1-6,10). What is interesting in this papyrus is the mention of exalted position of Ramesses II.

(1,1) Beginning of the Recital of the Victories of the Lord of Egypt. His Majesty (l.p.h) has built himself a castle whose name is Great-of-Victories. (1,2) It lies between Djahy and To-meri, and is full of food and victuals. It is after the fashion of On of Upper Egypt, and its duration is like (1,3) that of He-Ka-Ptah. The sun arises in its horizon and sets within it. Everyone has foresaken his (1,4) (own) town and settled in its neighbourhood.

Its western part is the House of Amun, its southern part the House of Seth. Astarte is (1,5) in its Levant, and Edjo in its northern part. (1,6) Ramesse-miamum (l.h) is in it as god, Mont-in-the-Two-Lands as herald, Sun-of-Rulers as vizier, Joy-of-Egypt (2,1) Beloved-of-Atum as mayor. The country has gone to its proper place.[11]

Here we see Ramesses II in four different aspects, viz., as god, herald, vizier and mayor. This is as if to show that he was everything to the capital, especially god, and commanded everything.

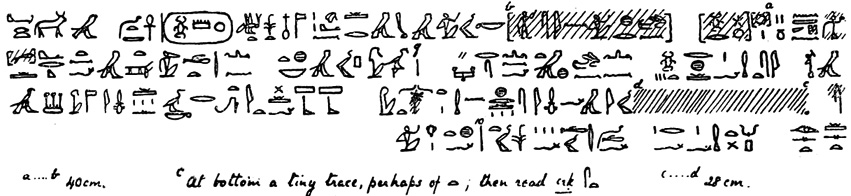

Papyrus Anastasi III is dated to the time of Ramesses II.[12] In the section “Report on the Delta Residence”, this payrus describes the beautiful environs of the city of Pi-Ramesses. The description has come down to us in a letter from a scribe called Pbēs to his master Amenemope, in which he describes how he reached the capital and how he found it in extremely good condition.

He then speaks about the antiquity of the town, how its ponds were filled with fish and its pools covered with birds, and its meadows verdant with herbage. But the most important description of Ramesses II is towards the end:

… The youths of Great-of-Victories are in festal attire every day; sweet moringa-oil is upon their heads, (3,3) (they) having the hair braided anew. They stand beside their doors, their hands bowed down with foliage and greenery of Pi-Hathor (3,4) and flax of the P3-hr- waters on the day of the entry of Usimare-setpenre (l.p.h), Mont-in-the-Two-Lands, on the morning of the feast of Khoiakh, (3,5) every man being like his fellow in uttering his petitions…. Dwell, be happy and stride freely about without stirring thence, Usimare-setpenre (l.p.h), Mont-in-the-Two-Lands, Ramesse-miamum (3,9) (l.p.h), the God.[13]

Ramesses II is called the god by the scribe Pbēs. This again affirms the fact that even the common folk treated the king as a divinity just like the officials.

PHARAOH AS GOD – FROM PHARAOH’S OWN WORDS

In the earlier section we saw how the Pharaohs were viewed by his subjects. It was seen that the subjects treated the ruler as a god who is alone, has no equal and takes care of his subjects like a parent. For them, he was one and the unique god. Moreover, the Pharaoh was also considered to have divine qualities such as omniscience. By turning the issue around on its head we can ask – how did the Pharaohs view themselves? The view of the Pharaohs about themselves is best seen in the hieroglyphs.

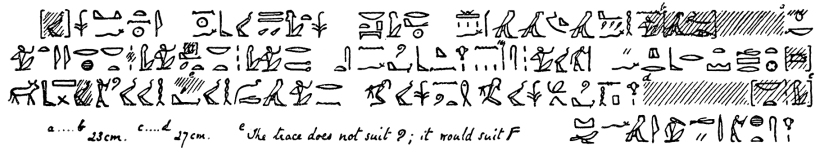

The rulers of Egypt were not themselves responsible for construction of temples, obelisks, etc., where the inscriptions were engraved; rather they had a team of architects who were responsible for executing the orders of the Pharaoh. The hieroglyphs give good information about the Pharaoh, his family, his cult and his courtiers. Let us consider three hieroglyphs from the time of Ramesses II (who had prenomen Usermaatre-setepenre and nomen Ramesses meryamun).

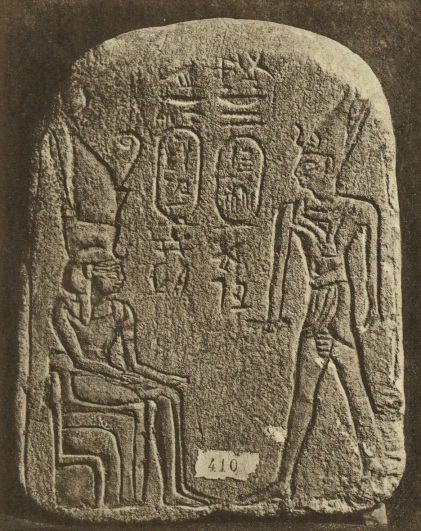

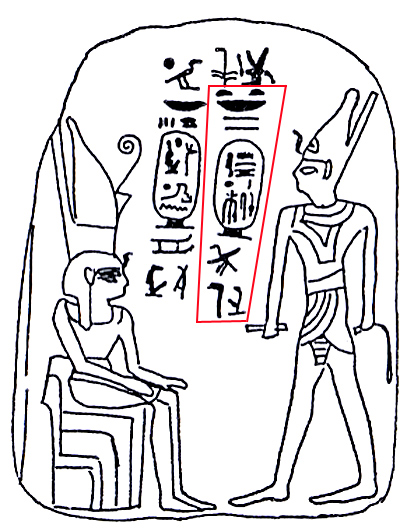

Stela no. 410 of Hildesheim Museum shows two people, one is standing wearing the double crown with the uraeus, a short skirt, a necklace and holds the so-called handkerchief or seal in one hand [Figure 1(a)]. He is called: “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Lord of the Two Lands ‘Ramesses-meryamun, the God’”.[14]

|  | |

| (a) |

| ||

| (b) |

(c)

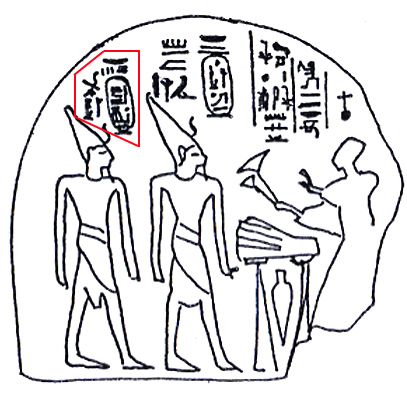

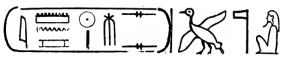

Figure 1: Stela no. (a) 410, (b) 1079 of the Hildesheim Museum. (c) These have an important inscription saying “Ramesses-meryamun, the god”. This inscription is marked inside a red box in both the stelas (a) and (b).[15]

On stela no. 1079 of Hildesheim Museum a man is depicted wearing a long garment tied at the waist, offering two flowers with his right hand. In front of him is a table laden with various kinds of offerings, and two stands with a vase between them [Figure 1(b)]. Opposite him are two statues, each wearing a short kilt, an artificial beard and the crown of Upper Egypt, with uraeus in front. Above these two statues and before them are the words: “Lord of the two Lands ‘Usermaatre-setpenre’ Monthu-in-the-Two-Lands” and “Lord of the diadems ‘Ramesses-meryamun’, the God”.[16]

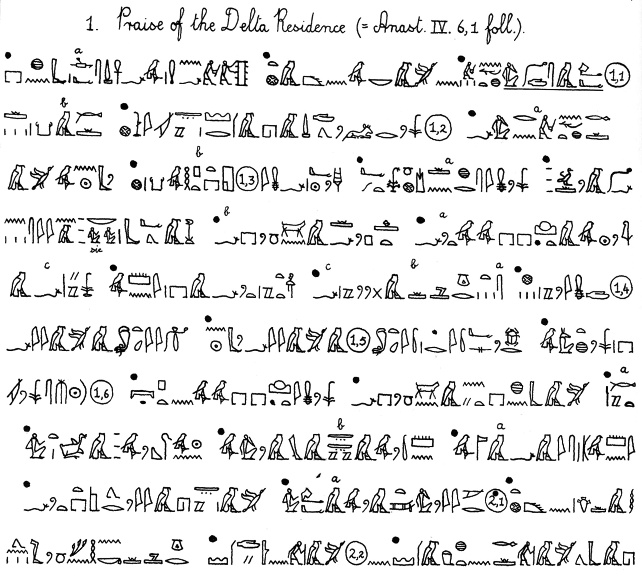

Figure 2: A relief in the Great Temple of Abu Simbel showing Ramesses II venerating Ramesses II.[17]

Our last example of the divine kingship in ancient Egypt comes from the Great Temple at Abu Simbel [Figure 2]. An interesting relief in the Great Temple of Abu Simbel shows the “Lord of Two Lands ‘Usermare-setpenre’” (= Ramesses II) offering to “Ramesses-meryamun” (= Ramesses II).

Obviously, Ramesses II is worshipping Ramesses II here. However, we also note that the worshipper and the one who is worshipped have two different names and that these names are pronomen and nomen of Ramesses II, respectively. A closer look at the iconography reveals that the worshipper and he who is worshipped are not identical.

He, to whom the offering is made, is adorned with a sun-disk and has a curved horn around his ear, depicting his divinity. Therefore, Ramesses II is not simply worshipping himself, but his divine self.[18]

As one can see from the examples just discussed, the Pharaoh exalted himself as Lord. The institution of Lordship in ancient Egyptian belief cannot be underestimated. It was the way in which ordinary Egyptians understood the residence of their gods on earth.[19]

PHARAOH AND HIS GODS

In the earlier sections we have seen what the views of Pharaoh and his subjects were concerning the kingship in ancient Egypt during the New Kingdom Period. In this section, let us deal with the issue of multiplicity of Egyptian gods and their relation to the ruler of Egypt.

In ancient Egypt, the basis of religion was not belief but cult, particularly the local cult which meant more to the inhabitants of a particular place. Consequently, many deities flourished simultaneously and people in ancient Egypt were ever-ready to adopt a new god or to change their views about the old. It has been estimated that over 2,000 gods and goddesses were attested in more than 3,000 years of Egyptian civilization.[20]

It is well-recognized that not all the gods were worshipped simultaneously, and over the course of Egyptian history one can observe the rise and decline of individual deities. Only a handful of deities from among the 2,000 or so were the recipient of a cult, with dedicated temples and priestly offerings.

The official state religion of Egypt concerned itself with promoting the well-being of the gods, which they reciprocated by maintaining the established order of the world. The vehicle through which the gods received favour, and in turn dispensed it, was the king, who was, in theory, the chief priest in every temple, aided by a hierarchy of priests.[21] Thus the king was unifying factor in Egyptian religious life.

The kings of ancient Egypt adopted a very business-like, quid pro quo approach, towards the gods, as seen in the texts carved on the walls of their temples. The king makes an offering to a god and the god reciprocates in kind. For example, if the king offers the god wine, the god in turn rewards the king with the gift of vineyards that produce the wine; if the royal offering is incense, the god promises the king that he shall have dominion over the land from whence the incense came.[22] But what if the god does not reciprocate the king’s offering in kind?

If they [i.e., gods] do not obey him, they will have neither food nor offerings. But the king takes one precaution. It is not he himself, as an individual, who speaks, but the divine power: “It is not I who say this to you, the gods, it is the Magic who speaks”.

When the Pharaoh completes his climb, magic at his feet “The sky trembles”, he asserts, “the earth shivers before me, for I am a magician, I possess magic”. It is also he who installs the gods on their thrones, thus proving that the cosmos recognises his omnipotence.[23]

In other words, if the gods did not reciprocate to the offerings of the king, they get demoted in status and standing. Conversely, those gods reciprocate in kind to the king are exalted and worshipped. Thus, the gods of Egypt were not truly independent gods; rather they were Pharaoh’s gods.

Their rise or decline was dependent upon the ruler of Egypt. There are numerous examples from ancient Egypt showing the rise and decline of gods. Monthu was a warrior god of Thebes who rose to prominence during the 11th Dynasty, but was supplanted by Amun during the 12th Dynasty.[24] In the 18th Dynasty, Aten became the prominent deity during the time of ‘heretic’ Pharaoh Akhenaten.[25] Atenism fell out of favour soon after Akhenaten’s death.

During the 19th Dynasty, in the time of Ramesses II, the three chief deities of the empire were Amun, Rēʿ, and Ptah. Since the deification of the living king reached its zenith during the time of Ramesses II, this exalted status resulted in him labelling his monuments with dedications illustrating his divine status such as “Ptah of Ramesses”,

“Amun of Ramesses”, “Rēʿof Ramesses” among others at various temples.[26] As Professor Kitchen puts it, such labels simply showed that these gods and others were nothing but “gods of Ramesses”.

In Nubia, some time after the completion of Abu Simbel, the “Temple of Ramesses II in the Domain of Re” was cut in the rock at Derr, further downstream on an important bend in the Nile. Later still, the Viceroy Setau had to construct two other temples to match it – one similarly related to Amun (at Wady es-Sebua) and one to Ptah (Gerf Hussein).

In these three, therefore, Amun, Re, and Ptah, the gods of Empire were ostensibly worshipped – but (as at Abu Simbel) the actual barque-image in the sanctuary was in fact that of the deified Ramesses II, as a form of Re, as “Amun of Ramesses”, and as “Ptah of Ramesses”.

Such temples, therefore, were almost additional ‘memorial-temples’ of the king. Not only Amun, Re and Ptah, but also other gods (Seth, Herishef, etc.) were gods “of Ramesses”, – and even goddesses: Udjo, Hathor, Nephthys, and Anath from Canaan.[27]

It was noted earlier that the Qur’an reported the distinction the chiefs held between Pharaoh and his gods. As for the latter, it is clear from our discussion that the Pharaoh indeed was different from his gods. He was responsible for enthroning and dethroning the gods depending upon whether or not they reciprocated to his offerings. Therefore, if a god was favoured, it was because of the Pharaoh who favoured him. In other words, the gods belonged to Pharaoh – they were his gods.

3. Conclusions

Reporting the statements of the Pharaoh and his Chiefs at the time of Moses, the missionaries suggest the Qur’an is in error with the established religious beliefs of ancient Egypt. Basing their knowledge on over a dozen internet websites, the missionaries claimed to have been successful in reconstructing the ancient Egyptian religion.

It goes without saying that one would generally not expect a detailed reconstruction of ancient Egyptian beliefs on a webpage “designed for children aged 7-11 years old” or on a tourism website. By their very nature none of these websites are intended to provide an in-depth discussion of the topic at hand.

A considered examination of a selection of primary sources from the New Kingdom period such as papyri, hieroglyphs and associated iconography, reveal the Pharaoh was considered as God, one who was able to enthrone and dethrone other gods depending on their perceived obedience to him. Such was Ramesses II excessive deification that he is even depicted as worshipping his own divine self. To sum up:

To the Egyptian the king was the centre of all existence. Because he was an entity both human and divine. He was the link between this world and the other. One Pyramid Text, (No. 1037), says of the king that ‘there is no limb of mine devoid of God’, which means that the king united all divine powers.[28]

The Qur’an reports the statements the Pharaoh and his chiefs made which are in consonance with established ancient Egyptian religious precepts. The Qur’an, however, condemns the claim of the Pharaoh being the god as false. The Pharaoh was neither God, nor the Lord most high.

And Allah knows best!

References & Notes

[1] M. Asad, The Message Of The Qur’an, 1984, Dar al-Andalus: Gibraltar, p. 595, footnote 36. Commenting on the verse 28:38, he says:

In view of the fact that the ancient Egyptians worshipped many gods, this observation is not to be taken literally; but since each of the Pharaohs was regarded as an incarnation of the divine principle as such, he claimed – and received – his people’s adoration as their “Lord All-Highest” (cf. 79:24), combining within himself, as it were, all the qualities attributable to gods.

[2] A good discussion can be seen in H. Frankfort, Kingship And The Gods: A Study Of Ancient Near Eastern Religion As The Integration Of Society & Nature, 1948, University of Chicago Press: Chicago (USA); J. von Beckerath, “König” in W. Heck & E. Otto (Eds.), Lexikon Der Ägyptologie, 1978, Volume III, Otto Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, col. 461 and also H. Brunner “König-Gott-Verhaltnis” in W. Heck & E. Otto (Eds.), Lexikon Der Ägyptologie, 1978, Volume III, op. cit., col. 461-464; For modern studies see J. Baines, “Kingship, Definition Of Culture, And Legitimation” in D. O’Connor & D. P. Silverman (Eds.), Ancient Egyptian Kingship, 1995, Probleme Der Ägyptologie – Volume 9, E. J. Brill: Leiden, pp. 3-47, especially pp. 22-34 for the nature of kingship in the New Kingdom Period; D. P. Silverman, “The Nature Of Egyptian Kingship” in D. O’Connor & D. P. Silverman (Eds.), Ancient Egyptian Kingship, 1995, op. cit., pp. 49-92

[3] For various usages of nṭr, please see A. Erman & H. Grapow, Wörterbuch Der Aegyptischen Sprache, 1928, Volume 2, J. C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung: Leipzig, pp. 358-364; Also see E. Hornung (Trans. J. Baines), Conceptions Of God In Ancient Egypt: The One And The Many, 1982, Routledge & Kegan Paul: London, pp. 42-49.

[4] This discussion, with slight modification, in this paragraph and the next is from B. Watterson, The Gods Of Ancient Egypt, 1984, B. T. Batsford Ltd.: London (UK), p. 36.

[5] D. P. Silverman,”Divinities And Deities In Ancient Egypt” in B. E. Shafer (Ed.) Religion In Ancient Egypt: Gods Myths, And Personal Practice, 1991, Routledge: London, p. 64.

[6] For an exhaustive discussion please see L. Habachi, Features Of The Deification Of Ramesses II, 1969, Abhandlungen Des Deutschen Archaölogischen Instituts Kairo Ägyptische Reihe – Volume 5, Verlag J. J. Augustin: Glückstadt; idem., “Khatâ‘na-Qantîr: Importance”, Annales Du Service Des Antiquités De L’Égypte, 1954, Volume 52, pp. 443-559, Plates I-XXXVII. Other important works are G. Roeder, “Ramses II Als Gott: Nach Den Hildesheimer Denksteinen Aus Horbet”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1926, Volume 61, pp. 57-67, Plates IV and V; M. Hamza, “Excavations Of The Department Of Antiquities At Qantîr (Faqus District) (Season, May 21st – July 7th, 1928)”, Annales Du Service Des Antiquités De L’Égypte, 1930, Volume 30, pp. 31-68, Plates I-IV.

[7] The inscription was published by K. Sethe, Urkunden Der 18. Dynastie: Historisch-Biographische Urkunden, 1909, Volume IV, J. C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung: Leipzig, IV 1077, 17-18. For translation of the inscription see A. H. Gardiner, “The Autobiography Of Rekhmerēʿ”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1925, Volume 60, p. 69.

[8] K. Sethe, Urkunden Der 18. Dynastie: Historisch-Biographische Urkunden, 1909, Volume IV, op. cit., IV 1074, 8-10. For translation of the inscription see A. H. Gardiner, “The Autobiography Of Rekhmerēʿ”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1925, op. cit., p. 66.

[9] K. Sethe, Urkunden Der 18. Dynastie: Historisch-Biographische Urkunden, 1909, Volume IV, op. cit., IV 1075, 13-14. For translation of the inscription see A. H. Gardiner, “The Autobiography Of Rekhmerēʿ”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1925, op. cit., p. 68.

[10] A. H. Gardiner, “The Delta Residence Of The Ramessides”, Journal Of Egyptian Archaeology, 1918, Volume 5, No. 3 (Part III), p. 187.

[11] The inscription was published in A. H. Gardiner, Late-Egyptian Miscellanies, 1937, Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca – VII, Édition de la Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth: Bruxelles, p. 12; Translation was done by R. A. Caminos, Late-Egyptian Miscellanies, 1954, Brown Egyptological Studies – I, Oxford University Press: London, p. 37; Also see A. H. Gardiner, “The Delta Residence Of The Ramessides – II”, Journal Of Egyptian Archaeology, 1918, op. cit., pp. 187-188.

[12] A. H. Gardiner, “The Delta Residence Of The Ramessides”, Journal Of Egyptian Archaeology, 1918, op. cit. (Part III), pp. 184-185.

[13] R. A. Caminos, Late-Egyptian Miscellanies, 1954, op. cit., p. 75; Also see A. H. Gardiner, “The Delta Residence Of The Ramessides”, Journal Of Egyptian Archaeology, 1918, op. cit. (Part III), pp. 186.

[14] L. Habachi, Features Of The Deification Of Ramesses II, 1969, op. cit., p. 32; G. Roeder, “Ramses II Als Gott: Nach Den Hildesheimer Denksteinen Aus Horbet”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1926, op. cit., pp. 62-63; L. Habachi, “Khatâ‘na-Qantîr: Importance”, Annales Du Service Des Antiquités De L’Égypte, 1954, op. cit., pp. 537-538.

[15] For (a) see G. Roeder, “Ramses II Als Gott: Nach Den Hildesheimer Denksteinen Aus Horbet”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1926, op. cit., Tafel V(3); L. Habachi, Features Of The Deification Of Ramesses II, 1969, op. cit., p. 31; For (b) see G. Roeder, “Ramses II Als Gott: Nach Den Hildesheimer Denksteinen Aus Horbet”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1926, op. cit., Tafel V(4); L. Habachi, Features Of The Deification Of Ramesses II, 1969, op. cit., p. 31; For (c) see L. Habachi, “Khatâ‘na-Qantîr: Importance”, Annales Du Service Des Antiquités De L’Égypte, 1954, op. cit., p. 550.

[16] L. Habachi, Features Of The Deification Of Ramesses II, 1969, op. cit., p. 31; G. Roeder, “Ramses II Als Gott: Nach Den Hildesheimer Denksteinen Aus Horbet”, Zeitschrift Für Ägyptische Sprache Und Altertumskunde, 1926, op. cit., pp. 62-63; L. Habachi, “Khatâ‘na-Qantîr: Importance”, Annales Du Service Des Antiquités De L’Égypte, 1954, op. cit., pp. 539-540.

[17] L. Habachi, Features Of The Deification Of Ramesses II, 1969, op. cit., Plate II(a).

[18] H. Te Velde, “Commemoration In Ancient Egypt”, in H. G. Kippenberg, L. P. van den Bosch et al., Visible Religion: Annual For Religious Iconography, 1982, Volume I – Commemorative Figures: Papers Presented To Dr. Th. P. Van Baaren On The Occasion Of His Seventieth Birthday, May 13, 1982, E. J. Brill: Leiden, p. 136.

[19] J. Assmann (Trans. D. Lorton), The Search For God In Ancient Egypt, 2001, Cornell University Press, pp. 18-19. Assmann says:

The divine realm of the Egyptians had a local dimension: that is to say, the Egyptians conceived of their deities as resident on earth. How was this residence interpreted? – first and foremost, as lordship. The kingdom of the Egyptian gods was emphatically “of this world.”

[20] S. E. Thompson, “Pantheon” in K. A. Bard & S. B. Shubert, (Eds.), Encyclopedia Of The Archaeology Of Ancient Egypt, 1999, Routledge: London & New York, pp. 607-608.

[21] B. Watterson, The Gods Of Ancient Egypt, 1984, op. cit., p. 36.

[22] ibid., p. 40.

[23] C. Jacq (Trans. J. M. Davis), Egyptian Magic, 1985, Aris & Phillips Ltd. & Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers: Chicago, p. 11.

[24] S. E. Thompson, “Pantheon” in K. A. Bard & S. B. Shubert, (Eds.), Encyclopedia Of The Archaeology Of Ancient Egypt, 1999, op. cit., p. 609; E. K. Werner, “Monthu” in D. B. Redford (Ed.), The Ancient Gods Speak: A Guide To Egyptian Religion, 2002, Oxford University Press: Oxford, pp. 230-231. “Amun” in T. Wilkinson, The Thames & Hudson Dictionary Of Ancient Egypt With 316 Illustrations, 163 In Colour, 2005, Thames & Hudson Ltd.: London, p. 25.

[25] Perhaps the best introduction to the religion of Akhenaten is by E. Hornung (Trans. D. Lorton), Akhenaten And The Religion Of Light, 1999, Cornell University Press: Ithaca (New York). Also see D. P. Silverman,”Divinities And Deities In Ancient Egypt” in B. E. Shafer (Ed.) Religion In Ancient Egypt: Gods Myths, And Personal Practice, 1991, op. cit., pp. 81-87.

[26] For a full record of assumption of such names by Ramesses II along with scholarly references see A. Gaber, “Aspects Of The Deification Of Some Old Kingdom Kings” in A. K. Eyma & C. J. Bennett (Eds.), A Delta-Man In Yebu: Occasional Volume Of The Egyptologists’ Electronic Forum No. 1, 2003, Universal Publishers: USA, pp. 29-31. For the inscriptions from time of Ramesses II mentioning such assumption of names see K. A. Kitchen, Ramesside Inscriptions: Translated & Annotated, Translations, 1996, Volume II – Ramesses II, Royal Inscriptions, Blackwell Publishers: Oxford (UK); idem., Ramesside Inscriptions: Translated & Annotated, Notes And Comments, 1999, Volume II – Ramesses II Royal Inscriptions, Blackwell Publishers: Oxford (UK); idem., Ramesside Inscriptions: Translated & Annotated, Translations, 2000, Volume III – Ramesses II, His Contemporaries, Blackwell Publishers: Oxford (UK).

[27] K. A. Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life And Times Of Ramesses II, King Of Egypt, 1982, Monumenta Hannah Sheen Dedicata – II, Aris & Phillips Ltd.: Warminster (England), p. 177.

[28] “King” in M. Lurker, The Gods And Symbols Of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Dictionary With 114 Illustrations, 1986, Thames and Hudson, p. 75.