𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐃𝐨 𝐖𝐞 𝐑𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐔𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧?

Mohamad Mostafa Nassar

Twitter:@NassarMohamadMR

𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐋𝐞𝐭 𝐮𝐬 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐜𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐨: 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐚𝐥𝐰𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐚𝐬 ‘𝐇𝐞/ هو’ 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐍𝐨𝐭 ‘𝐬𝐡𝐞/ هي’ | 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜𝟏𝟎𝟏

𝐒𝐮𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐲:

𝐅𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐞𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 “𝐇𝐞” 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐦 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐬:

(𝐚) 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 𝐢𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 “𝐡𝐞” 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡,

(𝐛) 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐨𝐝, 𝐚𝐧𝐝

(𝐜) 𝐚 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰.

𝟏. 𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐍𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐆𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫

𝐌𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫. 𝐍𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐝𝐞𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐩𝐡𝐲𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲: 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐥 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐚 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐱 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐥 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐚 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐱 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞. [𝟏]

𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐝𝐞𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐩𝐡𝐲𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲. 𝐓𝐨 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫, 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐦𝐮𝐬𝐭 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐬 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐅𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐡 𝐨𝐫 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜, 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐰𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐝𝐨𝐧’𝐭 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐚 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫.

𝐂𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐬𝐞 (𝐅𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐡 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐫”), 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞, 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐡𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐭 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐞” 𝐨𝐫 “𝐅𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐚”, 𝐢.𝐞., 𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐞 (𝐅𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐡 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐬𝐡𝐞”). 𝐊𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐢𝐲𝐲 (𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐫”), 𝐡𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫, 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐬𝐨 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐭 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐉𝐨𝐡𝐧” 𝐨𝐫 “𝐀𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐝”, 𝐢.𝐞., 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 (𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐡𝐞”).

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐛𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐢𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐲 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞. 𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐚 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬𝐧’𝐭 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐚 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫—𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 “𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐫”—𝐢𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐭 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧, “𝐢𝐭”, 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 “𝐡𝐞”, 𝐧𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 “𝐬𝐡𝐞”.

𝟐. 𝐏𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐆𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫-𝐍𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐍𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐬

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐛𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 (𝐨𝐫 𝐅𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐡) 𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐜𝐡. 𝐀 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐞𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡, 𝐢𝐟 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫, 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐬 𝐚 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧, 𝐮𝐬𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐩𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐮𝐥 𝐫𝐡𝐞𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐞𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐜𝐭. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐫𝐡𝐞𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐝𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐜𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐟𝐭𝐞𝐧 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐩𝐨𝐞𝐭𝐬. [𝟐] 𝐖𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐚𝐦 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐡, 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞, 𝐰𝐫𝐨𝐭𝐞,

𝐈𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭𝐥𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐠𝐚𝐢𝐞𝐭𝐲, 𝐈 𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐢𝐧,

𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐡𝐨𝐩𝐞 𝐢𝐭𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐈 𝐤𝐧𝐞𝐰 𝐨𝐟 𝐩𝐚𝐢𝐧;

𝐅𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐝 𝐡𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐚𝐭

𝐀𝐭 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐬, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐞 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐠 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐨𝐤 𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐭,

𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐝 𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞, 𝐩𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐮𝐩𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝, 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐝,

𝐓𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡 𝐩𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐲𝐞𝐭 𝐮𝐧𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐝, 𝐚 𝐛𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐫𝐨𝐚𝐝 …[𝟑]

𝐍𝐨𝐭𝐞 𝐡𝐨𝐰 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐡 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫-𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐚𝐛𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐭 𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐬 “𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭” 𝐚𝐧𝐝 “𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞”, 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐞𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧, “𝐡𝐞𝐫”.

𝐋𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐬 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜, 𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡, 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐧𝐨 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐜𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐲 𝐧𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐬𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐬 (𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐬𝐮𝐧”) 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐪𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐫 (𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐦𝐨𝐨𝐧”) 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐛𝐚𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐨𝐧 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐈𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐥 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐞𝐝, 𝐢𝐧 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬, 𝐭𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐡𝐢𝐲𝐚 (𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐬𝐡𝐞”), 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐪𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 (𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐡𝐞”).

𝟑. 𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐆𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐍𝐨𝐭 𝐌𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐠𝐲𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜

𝐈𝐟 𝐢𝐧𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞, 𝐢𝐧𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐠𝐲𝐧𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐬𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐪𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦 𝐩𝐨𝐞𝐭, 𝐌𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐚𝐛𝐛𝐢, 𝐰𝐫𝐨𝐭𝐞,

𝐰𝐚 𝐦𝐚 𝐚𝐥-𝐭𝐚’𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐮 𝐥𝐢 𝐢𝐬𝐦𝐢 𝐚𝐥-𝐬𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐬𝐢 `𝐚𝐲𝐛𝐮𝐧

𝐰𝐚 𝐥𝐚 𝐚𝐥-𝐭𝐚𝐝𝐡𝐤𝐢𝐫𝐮 𝐟𝐚𝐤𝐡𝐫𝐮𝐧 𝐥𝐢 𝐚𝐥-𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐚𝐥𝐢

𝐍𝐞𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐚 𝐝𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐜𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝, 𝐬𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐬,

𝐧𝐨𝐫 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐚 𝐬𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐝𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐪𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐫 [𝐨𝐫, 𝐚𝐥-𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐚𝐥]

𝟒. 𝐃𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 “𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡” 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 (𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐛𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐮𝐠𝐞 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭!). 𝐈𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡, 𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 “𝐇𝐞” 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐬𝐦 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐬𝐨𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫. 𝐍𝐞𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫, 𝐚𝐬 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞, 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐠𝐲𝐧𝐲.

𝐓𝐨 𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐦 𝐚 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐟𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞, “𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐬𝐨𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐮𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐇𝐢𝐦.” (𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧, 𝟒𝟐:𝟏𝟏) 𝐖𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐬, 𝐢𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐝, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐧𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦 𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐦𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐜𝐞.

𝐂𝐡𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬, 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞, 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐡𝐞𝐭 𝐉𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐬 (𝐮𝐩𝐨𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐦 𝐛𝐞 𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐞) 𝐡𝐢𝐦𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐆𝐨𝐝 (𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐛𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐮𝐠𝐞!) 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐚 𝐦𝐚𝐧. 𝐅𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐝𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐂𝐡𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐨𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐬, 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐚𝐬 “𝐇𝐞” 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐦𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐓𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲. 𝐌𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐚𝐫𝐠𝐮𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫-𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐲𝐚𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐂𝐡𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲. [𝟒]

𝐏𝐨𝐥𝐲𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐬𝐦, 𝐭𝐨𝐨, 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐠𝐨𝐝𝐬. 𝐈𝐝𝐨𝐥𝐬 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐲 𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐦𝐞 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐨𝐫 𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐨𝐭𝐡 𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝. 𝐖𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐱𝐜𝐞𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦, 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐨𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐝𝐞𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐞𝐱𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭. 𝐀𝐛𝐬𝐨𝐥𝐮𝐭𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐪𝐮𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐚𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐝 (𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲), 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐚𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦.

𝐓𝐨 𝐚 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦 𝐰𝐡𝐨 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐚𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦, 𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐲. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭 𝐣𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐚𝐧, 𝐈𝐦𝐚𝐦 𝐚𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐰𝐢, 𝐰𝐫𝐨𝐭𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐞𝐥𝐞𝐛𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐞𝐝,

𝐇𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐥𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐲𝐨𝐧𝐝 𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐬, 𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐬, 𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐬, 𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐛𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝—𝐮𝐧𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬—𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐢𝐱 𝐝𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐝𝐨 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐬𝐬 𝐇𝐢𝐦. [𝟓]

𝐚𝐧𝐝,

𝐖𝐡𝐨𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐮𝐭𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐝. 𝐖𝐡𝐨𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐡𝐞𝐞𝐝, 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐫𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐝𝐨, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐤𝐧𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡’𝐬 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐝𝐨 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬. [𝟔]

𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐇𝐢𝐦𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐚𝐧 𝐮𝐧𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞. 𝐇𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐬, “𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐬𝐨𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐮𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐇𝐢𝐦.” (𝟒𝟐:𝟏𝟏) 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐒𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐭 𝐚𝐥-𝐈𝐤𝐡𝐥𝐚𝐬, 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐬 𝐦𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦 𝐜𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐝𝐫𝐞𝐧 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞, 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐬, ” 𝐒𝐚𝐲, “𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐭𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐎𝐧𝐞. 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐁𝐞𝐬𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐚𝐥𝐥, 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐧𝐨𝐧𝐞. 𝐇𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐠𝐨𝐭 𝐧𝐨𝐭, 𝐧𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐇𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐠𝐨𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐧. 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐇𝐢𝐦 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐧𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐛𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐲𝐨𝐧𝐞.” (𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧, 𝟏𝟏𝟐:𝟏—𝟒) 𝐈𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐜𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐮𝐧𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐲 𝐚 𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐚 𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐬𝐦.

𝟓. 𝐒𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐝

𝐈𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐬𝐦, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐧𝐞𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐰𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐡𝐢𝐲𝐚. 𝐖𝐡𝐲, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧, 𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐬𝐞 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐡𝐢𝐲𝐚?

𝐁𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐨𝐫𝐦, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐱𝐜𝐞𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐒𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲. [𝟕]

𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐲, 𝐡𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫, 𝐛𝐞 𝐚 𝐝𝐞𝐞𝐩𝐞𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐬𝐝𝐨𝐦. 𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐈 𝐚𝐬𝐤𝐞𝐝 𝐦𝐲 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐒𝐡𝐚𝐲𝐤𝐡 `𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐮𝐥 𝐊𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐦 𝐓𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐚𝐧 (𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐞 𝐡𝐢𝐦) 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐨𝐥𝐝 𝐦𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 𝐧𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐩𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐫—𝐫𝐢𝐡—𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐥𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐫𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥—𝐫𝐢𝐲𝐚𝐡. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐫 𝐫𝐢𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐢𝐲𝐚𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞. [𝟖] 𝐌𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐩𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐮𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐲; 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐥𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐲. [𝟗]

𝐎𝐮𝐫 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩: “𝐈 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐣𝐢𝐧𝐧 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐚𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐌𝐞.” (𝟓𝟏:𝟓𝟔) 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐚𝐧𝐭’𝐬 𝐮𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐭𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐲 (𝐣𝐮𝐬𝐭 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧). 𝐋𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐮𝐥 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐩𝐬 𝐮𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐳𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐋𝐨𝐫𝐝. [𝟏𝟎]

𝟔. 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

𝐅𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐞𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 “𝐇𝐞” 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐦 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐬.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐮𝐰𝐚 𝐢𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 “𝐡𝐞” 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡. 𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐜𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐝𝐞𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐛𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡, 𝐢𝐭 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐧𝐨 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐞𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐨𝐝. 𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐡𝐢𝐬𝐦, 𝐢𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐨𝐬𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐚 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐨𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐚𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐢𝐭 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐟 𝐭𝐨 𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐞 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐆𝐨𝐝.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰. 𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬 𝐚 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐠𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐆𝐨𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐨𝐟 𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐝 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 “𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡” 𝐭𝐨 𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐝 𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐨𝐟 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐌𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐫.

𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐇𝐢𝐠𝐡 𝐤𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐬𝐭.

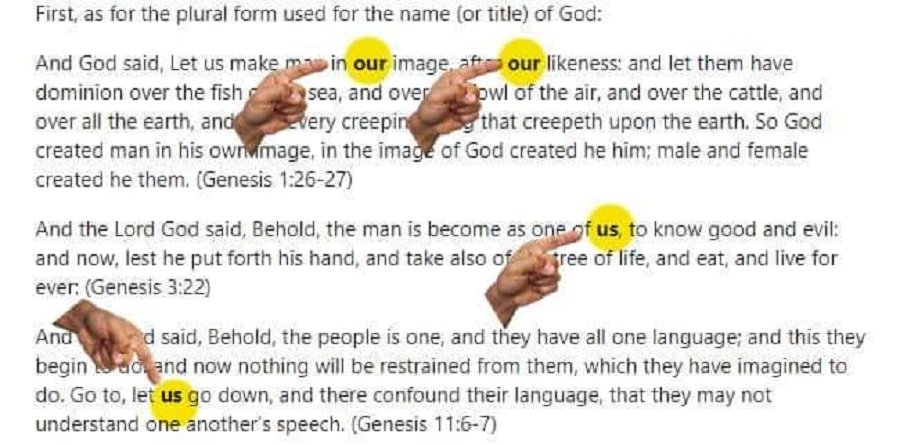

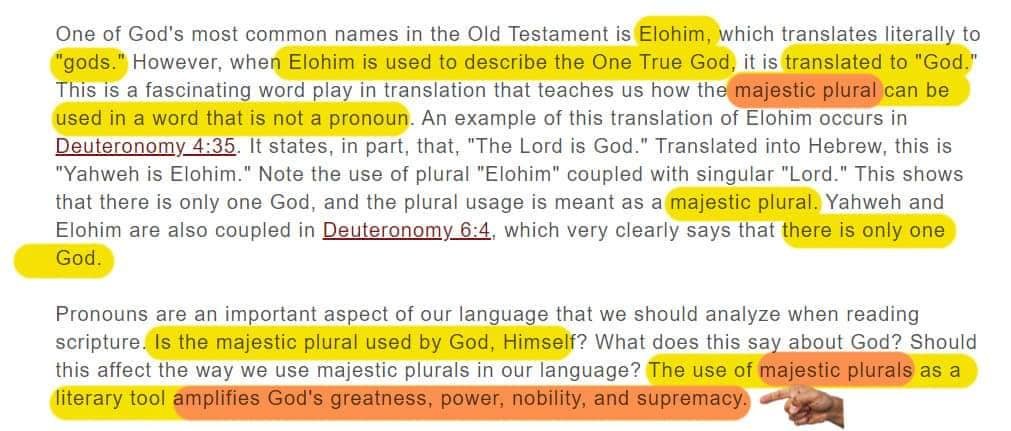

𝐈𝐧 𝐜𝐚𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐡𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐚𝐜𝐤 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 “𝐑𝐨𝐲𝐚𝐥 𝐖𝐞” (𝐖𝐞, 𝐔𝐬, 𝐎𝐮𝐫) 𝐢𝐧 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐥𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐇𝐨𝐥𝐲 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧. 𝐑𝐨𝐲𝐚𝐥 𝐖𝐞 (𝐌𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐏𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥) 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐁𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞.

𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐊𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐬 𝐁𝐞𝐬𝐭.

𝐑𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬:

The use of the plural “We” by God in the Quran- The Majestic We

Why Quran uses masculine pronouns (He/Him/His) for Allah?

God using the plural for Himself

The Concept of “We” as used in The Qur’an by Allah

𝐍𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬:

[𝟏] 𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐚 𝐬𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐥𝐚𝐫 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐎𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐬𝐭 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐥𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐜𝐨𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐩𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐒𝐢𝐝𝐚𝐡, 𝐪𝐮𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐀𝐛𝐮 `𝐀𝐥𝐢 𝐚𝐥-𝐅𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐢, “𝐀 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐚 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐱 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧 (𝐢.𝐞., 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐚 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠). 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 … 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐰𝐨 𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲: 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠.” (𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐒𝐢𝐝𝐚𝐡, 𝐚𝐥-𝐌𝐮𝐤𝐡𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐬, 𝐀𝐛𝐰𝐚𝐛 𝐚𝐥-𝐦𝐮𝐝𝐡𝐚𝐤𝐤𝐚𝐫 𝐰𝐚 𝐚𝐥-𝐦𝐮’𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐡) “𝐅𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠” 𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐚 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲; “𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠” 𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐚 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲.

[𝟐] 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐰𝐚𝐬𝐧’𝐭 𝐚𝐥𝐰𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐬𝐞. 𝐎𝐥𝐝 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡, 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐅𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐡, 𝐡𝐚𝐝 𝐧𝐨 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫. 𝐀𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐨𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐎𝐱𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 (𝐎𝐄𝐃) 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐮𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬, 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠, “𝐈𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐲 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐚𝐲 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐜𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐛𝐞 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐜𝐭.” 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐎𝐄𝐃 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐪𝐮𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝟏𝟑𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝟏𝟗𝐭𝐡 𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬. (𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐜𝐭 𝐄𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐎𝐱𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲, (𝐎𝐱𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐔𝐧𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬, 𝟏𝟗𝟕𝟏) 𝟏.𝟏𝟐𝟔𝟗)

[𝟑] 𝐖𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐚𝐦 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐡, 𝐀𝐧 𝐄𝐯𝐞𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐖𝐚𝐥𝐤.

[𝟒] 𝐀𝐛𝐮 𝐉𝐚𝐟𝐚𝐫 𝐚𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐰𝐢, 𝐚𝐥-𝐀𝐪𝐢𝐝𝐚 𝐚𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐰𝐢𝐲𝐲𝐚, 𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝟕 (𝐮𝐧𝐩𝐮𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐲 𝐇𝐚𝐦𝐳𝐚 𝐊𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐢).

[𝟓] 𝐀𝐛𝐮 𝐉𝐚𝐟𝐚𝐫 𝐚𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐰𝐢, 𝐚𝐥-𝐀𝐪𝐢𝐝𝐚 𝐚𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐰𝐢𝐲𝐲𝐚, 𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝟓 (𝐮𝐧𝐩𝐮𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐲 𝐇𝐚𝐦𝐳𝐚 𝐊𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐢).

[𝟔] “𝐍𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐛𝐲 𝐝𝐞𝐟𝐚𝐮𝐥𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐬𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐫𝐲.” (𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐒𝐢𝐝𝐚, 𝐚𝐥-𝐌𝐮𝐤𝐡𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐬, 𝐀𝐛𝐰𝐚𝐛 𝐚𝐥-𝐦𝐮𝐝𝐡𝐚𝐤𝐤𝐚𝐫 𝐰𝐚 𝐚𝐥-𝐦𝐮’𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐡)

[𝟏𝟏] “𝐈𝐧 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐭, 𝐛𝐲 𝐟𝐚𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐩𝐢𝐜𝐮𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐃𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐍𝐚𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐥-𝐑𝐚𝐡𝐦𝐚𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐥𝐥-𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐞. 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐢𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐤𝐞𝐝 𝐮𝐩𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐡𝐞𝐭 (𝐬.𝐰.𝐬.) 𝐡𝐢𝐦𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟, 𝐰𝐡𝐨 𝐭𝐚𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐫𝐚𝐡𝐦𝐚, 𝐥𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐮𝐭𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐫𝐚𝐡𝐢𝐦, 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛. (𝐁𝐮𝐤𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐢, 𝐀𝐝𝐚𝐛, 𝟏𝟑) 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐬𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐱 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐝𝐢𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐚𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐮𝐬, 𝐚𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐲𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐦𝐬, 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐢𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞; 𝐚𝐥𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 ‘𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐡’ 𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐮𝐭𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞 𝐪𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐲 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐫 𝐛𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐲.”

[𝟗] 𝐍𝐨𝐧-𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐩𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞.

[𝟏𝟎] 𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐊𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐫 𝐜𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐀𝐛𝐢 𝐇𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐦’𝐬 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐮𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐈𝐛𝐧𝐔𝐦𝐚𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐢𝐝, “𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝: 𝐟𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐲, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐟𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐩𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐚𝐭, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐮𝐛𝐚𝐬𝐡𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐚𝐭, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐚𝐥𝐚𝐭, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐲𝐚𝐭. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐩𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐪𝐢𝐦, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐫𝐬𝐚𝐫 (𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐰𝐨 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐧 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝), 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐢𝐟, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐪𝐚𝐬𝐢𝐟 (𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐰𝐨 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐧 𝐬𝐞𝐚).” (𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐊𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐫, 𝐓𝐚𝐟𝐬𝐢𝐫 𝐈𝐛𝐧 𝐊𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐫, 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐧 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧, 𝟑𝟎:𝟓𝟏) 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐝 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐝𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐝𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐯𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐝𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐝𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐩𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬.

𝐒𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐜𝐞: 𝐁𝐚𝐬𝐫𝐢𝐚 𝐄𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧