𝐃𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐚 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐢𝐬 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐞𝐝? 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 (𝟖𝟔:𝟔-𝟕)

Mohamad Mostafa Nassar

Twitter:@NassarMohamadMR

“𝐌𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐥𝐞𝐜𝐭 𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦. 𝐇𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝, 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬.” 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐂𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝟖𝟔, 𝐕𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟓 𝐭𝐨 𝟕

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐫𝐲𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐥𝐨𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐯𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐁𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐑𝐢𝐛𝐜𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐥𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐇𝐨𝐥𝐲 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝.

𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐄𝐱𝐚𝐥𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐇𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐧 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐥𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧

“𝐋𝐞𝐭 𝐩𝐞𝐨𝐩𝐥𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦! ˹𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐞˺ 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐚 𝐬𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝, 𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐦𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐜𝐚𝐠𝐞. 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 (𝟖𝟔:𝟓-𝟕)

𝐘𝐞𝐬, 𝐰𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐢𝐬 “𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐞𝐝” 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐬, 𝐡𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐜𝐚𝐠𝐞.

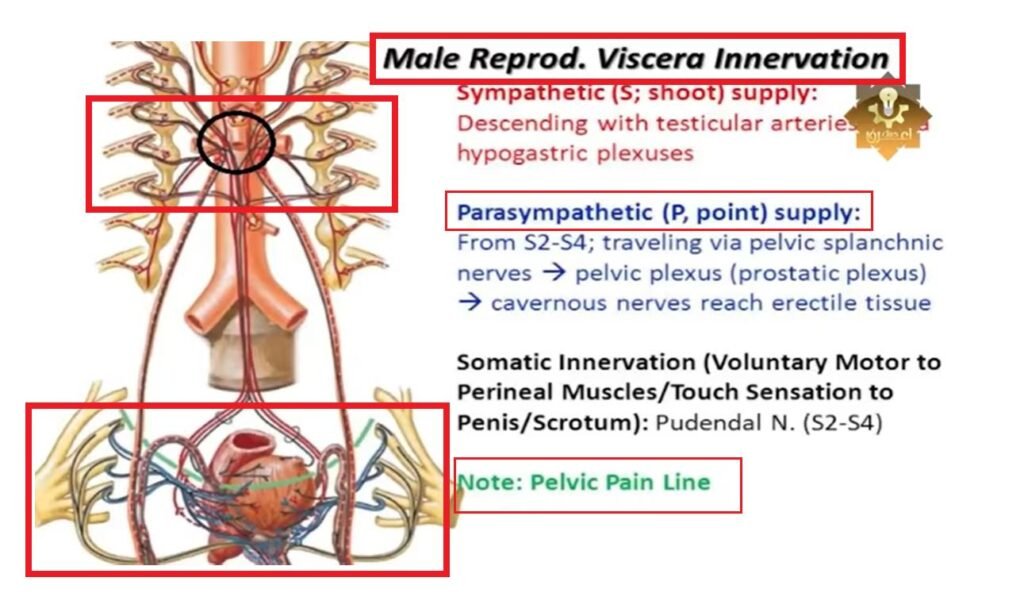

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐅𝐄𝐄𝐃𝐒 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐓𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐁𝐄𝐓𝐖𝐄𝐄𝐍 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐒𝐏𝐈𝐍𝐄 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐑𝐈𝐁𝐒 𝐄𝐗𝐀𝐂𝐓𝐋𝐘 𝐚𝐬 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐥𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐚𝐢𝐝- 𝐂𝐡𝐞𝐜𝐤 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐏𝐡𝐨𝐭𝐨 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐂𝐇𝐄𝐂𝐊 𝐓𝐇𝐈𝐒 𝐌𝐄𝐃𝐈𝐂𝐀𝐋 𝐑𝐄𝐅𝐄𝐑𝐄𝐍𝐂𝐄 𝐇𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐨𝐧’𝐬 𝐏𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐌𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐢𝐧𝐞

𝟐𝟏𝐬𝐭 𝐄𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 (𝐕𝐨𝐥.𝟏 & 𝐕𝐨𝐥.𝟐)

𝟏𝟐𝟔𝟒𝟐𝟔𝟖𝟓𝟎𝟓 · 𝟗𝟕𝟖𝟏𝟐𝟔𝟒𝟐𝟔𝟖𝟓𝟎𝟒

𝐁𝐲 𝐉𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐩𝐡 𝐋𝐨𝐬𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐳𝐨, 𝐀𝐧𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐧𝐲 𝐒. 𝐅𝐚𝐮𝐜𝐢, 𝐃𝐞𝐧𝐧𝐢𝐬 𝐋. 𝐊𝐚𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫, 𝐒𝐭𝐞𝐩𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐇𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐫, 𝐃𝐚𝐧 𝐋𝐨𝐧𝐠𝐨, 𝐉. 𝐋𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐲 𝐉𝐚𝐦𝐞𝐬𝐨𝐧

© 𝟐𝟎𝟐𝟐 | 𝐏𝐮𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝: 𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐜𝐡 𝟕, 𝟐𝟎𝟐𝟐

𝐀 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐠𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬:

“𝐒𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐢𝐬𝐧’𝐭 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐫𝐢𝐛 𝐜𝐚𝐠𝐞; 𝐬𝐨, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐬 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞.”

𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐯𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞. 𝐈𝐟 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐫 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐨𝐫𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐢𝐟 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐭 𝐨𝐝𝐝𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞. 𝐖𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐛𝐲 𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐞𝐦𝐩𝐢𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐨𝐛𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐞𝐱𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐮𝐧𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞𝐥𝐲 𝐭𝐨 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞. 𝐈𝐭 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐦𝐚𝐲 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐝𝐮𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐧𝐞𝐰 𝐝𝐚𝐭𝐚 𝐨𝐫 𝐨𝐛𝐬𝐞𝐫𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐭 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐝𝐨 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭 𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐝𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐨𝐫.

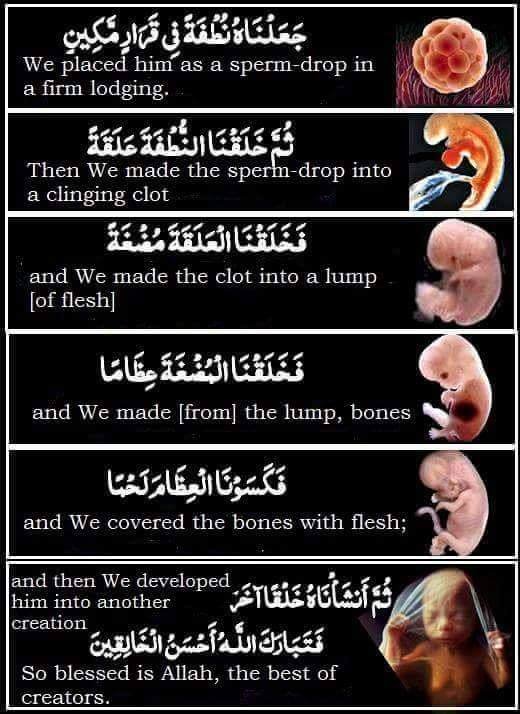

𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 (𝟐𝟑:𝟏𝟑-𝟏𝟒)

𝟏𝟑. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐖𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐝 𝐡𝐢𝐦 𝐚𝐬 𝐚 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦-𝐝𝐫𝐨𝐩 (𝐳𝐲𝐠𝐨𝐭𝐞) 𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐬𝐞𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞 (𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛).

𝟏𝟒. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐖𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐝𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐳𝐲𝐠𝐨𝐭𝐞 𝐚 𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐬 (𝐜𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐮𝐬 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐚 𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐜𝐡).

𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐖𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐥𝐮𝐦𝐩, 𝐥𝐨𝐨𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐰𝐞𝐝 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐞𝐞𝐭𝐡.

𝐎𝐮𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐰𝐞𝐝 𝐥𝐮𝐦𝐩, 𝐖𝐞 𝐛𝐮𝐢𝐥𝐭 𝐚 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐖𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐟𝐥𝐞𝐬𝐡 (𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐦𝐮𝐬𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬).

𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐧 (𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐡𝐢𝐦) 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐚𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦, 𝐖𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐡𝐢𝐦 (𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲) 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐧𝐞𝐰 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐁𝐞𝐬𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐬, 𝐛𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡𝐭 (𝐡𝐢𝐦 𝐮𝐩 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐨𝐝𝐲).

𝐁𝐞𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐬𝐮𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐝, 𝐢𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐞𝐯𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬:

- 𝐘𝐚𝐤𝐡𝐫𝐮𝐣𝐮: 𝐈𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐤𝐡𝐚̄ 𝐫𝐚̄ 𝐣𝐢̄𝐦 (خ ر ج). 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐭, 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞, 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞, 𝐭𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐭, 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐞.𝟏

- 𝐀𝐥- 𝐒̣𝐮𝐥𝐛: 𝐈𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐬̣𝐚̄𝐝 𝐥𝐚̄𝐦 𝐛𝐚̄ (ص ل ب) . 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐫 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞.𝟐 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐛𝐞 𝐚 𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐚̄𝐲𝐚𝐡 (𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫) 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐚 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞.𝟑 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐝 𝐨𝐫 𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐝.

- 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐚̄𝐢𝐛: 𝐈𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐚̄ 𝐫𝐚̄ 𝐛𝐚̄ (ت ر ب). 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞, 𝐮𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐫 𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐭, 𝐨𝐫 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬.𝟒 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐚 𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐚̄𝐲𝐚𝐡 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐚 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞.𝟓

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐬𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐬:

- 𝟏) 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬. 𝐄𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐢𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬.

- 𝟐) 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐥𝐨𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬.

- 𝟑) 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐬𝐞𝐱𝐮𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞, 𝐛𝐲 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐣𝐚𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦 𝐝𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞.

𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧:

𝐀 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐝. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐨𝐫 𝐚 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐟 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐢𝐭 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝. 𝐍𝐮𝐭̣𝐟𝐚𝐭 (نُّطْفَة) 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐬𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐝𝐫𝐨𝐩 𝐨𝐟 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝.𝟔 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐦𝐚̄’𝐚 (مَآء) 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫.𝟕

𝐒𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐝. 𝐄𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐢𝐟 𝐢𝐭 𝐝𝐢𝐝 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐢𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐛𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞. 𝐀𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐛𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐰, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐀𝐥-𝐒̣𝐮𝐥𝐛 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬. 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬 (𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐚̄𝐢𝐛). 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞𝐚 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐮𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐰𝐞𝐚𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬.

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐚 𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐠𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐩 𝐨𝐟 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐠𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐚 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐨𝐫. 𝐈𝐧 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐭, 𝐚𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝 𝟕𝟎% 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐣𝐚𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐯𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐥 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝 𝟐𝟎% 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝟓% 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐮𝐥𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐫𝐞𝐚.𝟖

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐯𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬, 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐛𝐮𝐥𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐞𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬. 𝐈𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐥𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐜𝐨𝐜𝐜𝐲𝐱.

𝐀𝐬 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐯𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬, 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐛𝐮𝐥𝐛𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐛𝐨𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐩𝐡𝐲𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲.

𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧:

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐬. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐜𝐥𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞. 𝐀𝐥-𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐮𝐛𝐢 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐈𝐛𝐧 ‘𝐀𝐭𝐢𝐲𝐲𝐚 𝐛𝐨𝐭𝐡 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐞𝐱𝐞𝐠𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐤.𝟗 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐢𝐭 𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧.

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫. 𝐌𝐮𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐝 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐊𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐅𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐝 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐟𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐨𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐒𝐭𝐮𝐝𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐭 𝐒𝐎𝐀𝐒, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐨𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐉𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐒𝐭𝐮𝐝𝐢𝐞𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝’𝐬 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧. 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐚 𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝟖𝟔𝐭𝐡 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐒𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐡 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬.

𝐓𝐨 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝟖𝟔 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐚 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐨𝐧 𝐦𝐮𝐬𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐠𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐟𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐫𝐮𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧.𝟏𝟎 𝐀𝐥𝐥 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞.

𝐎𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐠𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐝, 𝐚𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐟𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐦𝐮𝐬𝐭 𝐛𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝. 𝐒𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐡 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪 𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐫𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐝 𝐝𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐌𝐞𝐜𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐀𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐨𝐟 𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐌𝐞𝐜𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪 𝐞𝐱𝐡𝐢𝐛𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬. 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐐𝟖𝟔: 𝟓-𝟕 𝐚𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐬:

“𝐌𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐥𝐞𝐜𝐭 𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦. 𝐇𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞”.𝟏𝟏

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞, 𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦, 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐦𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 “𝐬𝐩𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝” 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐟𝐭 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟔 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐞𝐬 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐭𝐨 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧 𝐦𝐚𝐲 𝐬𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐭𝐨𝐨 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐮𝐝𝐝𝐞𝐧. 𝐇𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫, 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐮𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐩𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐨 𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐞, 𝐠𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐧 𝐡𝐨𝐰 “𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐬𝐞𝐝” 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐚𝐥𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐲 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐥𝐨𝐧𝐠𝐞𝐫, 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞, 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐫𝐲𝐨 𝐢𝐧 𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐫 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐬.𝟏𝟐 𝐅𝐨𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐟𝐚𝐦𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐚𝐫 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐝 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐫 𝐥𝐨𝐧𝐠𝐞𝐫 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐢𝐥𝐲.

𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐲 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐝 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧:

𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐥𝐲, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐟𝐨𝐫 ‘𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠’ 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐘𝐚𝐤𝐡𝐫𝐮𝐣. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐢𝐧 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐨𝐢𝐥, 𝐨𝐟 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛𝐬, 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐬.𝟏𝟑 𝐅𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐬𝐭𝐲𝐥𝐞, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐘𝐚𝐤𝐡𝐫𝐮𝐣 𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝟖𝟔 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧; 𝐬𝐨, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧.

𝐈𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐔𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐤𝐡𝐚̄ 𝐫𝐚̄ 𝐣𝐢̄𝐦 (خ ر ج), 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐘𝐚𝐤𝐡𝐫𝐮𝐣 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬:

“𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐭, 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞, 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞, 𝐭𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐭, 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐞, 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭.”𝟏𝟒

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐘𝐚𝐤𝐡𝐫𝐮𝐣 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝟓𝟑 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐬. 𝐌𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐫 𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐚 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐡 (𝐐𝟑𝟎:𝟐𝟓), 𝐭𝐨 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐰 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 (𝐐𝟐𝟑:𝟐𝟎), 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 (𝐐𝟖𝟔:𝟕), 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐠𝐨 𝐨𝐮𝐭, 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐱𝐢𝐭, 𝐭𝐨 𝐠𝐨 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐡 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐞 (𝐐𝟓:𝟐𝟐). 𝐐𝟑𝟎:𝟐𝟓 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐒𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐡 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪.

𝐐𝟐𝟑:𝟐𝟎 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐚 𝐦𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧; 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐲 𝐚 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐦𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐚𝐬 𝐚 𝐧𝐞𝐰𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲. 𝐐𝟓:𝟐𝟐 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐩𝐞𝐨𝐩𝐥𝐞 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚 𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝; 𝐚𝐠𝐚𝐢𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐬 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛, 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐭𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝.

𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐥𝐲, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐚 𝐛𝐚𝐛𝐲 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧 𝐟𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡 𝐨𝐟 𝐚 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞, 𝐝𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐡, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚 𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞 𝐚𝐠𝐚𝐢𝐧. 𝐈𝐟 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐯𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚𝐧 𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐝𝐞𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐩𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫.

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐝𝐥𝐲, 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟖 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬: “𝐆𝐨𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐛𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐡𝐢𝐦 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐞”. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞-𝐛𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐡 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟖 𝐢𝐬 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐧𝐞𝐝, 𝐢𝐧 𝐛𝐨𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬.𝟏𝟓 𝐈𝐭 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐚𝐝𝐝𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐟 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟖 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐞𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐬 𝐰𝐞𝐥𝐥 𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬.

𝐀𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐩𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐭, 𝐚 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐫𝐚𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐝. 𝐈𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐰 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐰𝐡𝐲 𝐝𝐢𝐝 𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐚𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬?

𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐰𝐞𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐫 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐨𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐰𝐚𝐲, 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐝 𝐚 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 “𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐬𝐭 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐧𝐨𝐮𝐧”.𝟏𝟔

𝐀𝐥𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐧𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐝, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐲 𝐛𝐞 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐱𝐮𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝, 𝐢𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐛𝐞 𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐐𝟔𝟖:𝟕.

𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬:

𝟏) 𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐞𝐱𝐚𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐫 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐥𝐲.𝟏𝟕

𝟐) 𝐒𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝, 𝐧𝐨 𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭𝐮𝐚𝐥 𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐬𝐮𝐩𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐚 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐚𝐧’𝐬 𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞. 𝐀𝐥𝐥 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐰𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬 𝐪𝐮𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐝𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐝𝐥𝐲 𝐞𝐪𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐱𝐞𝐠𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐩𝐥𝐞: 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄

𝟑) 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐮𝐛𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐨𝐥𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐛𝐞 𝐮𝐧𝐛𝐚𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐠𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬. 𝐓𝐚𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐧𝐠𝐞𝐫 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝟕 𝐚𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐧 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧.

𝐌𝐚𝐣𝐝 𝐛. 𝐀𝐡𝐦𝐚𝐝 𝐌𝐚𝐤𝐤𝐢, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫, 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐢𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐰𝐧 𝐞𝐱𝐞𝐠𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐬. 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐧 𝐐𝟖𝟔:𝟔-𝟕, 𝐌𝐚𝐤𝐤𝐢 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 “𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐚 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫”.𝟏𝟖 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰, 𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞, 𝐝𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐭 𝐚𝐥𝐥.

𝐈𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐥𝐝 𝐛𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐒𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞. 𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐪𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐫𝐚𝐦𝐞𝐝 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐚𝐬 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐦𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐥𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠. 𝐀𝐡𝐦𝐚𝐝 𝐃𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐥, 𝐢𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐠𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐥 𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐩𝐡 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐮𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭, 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐡𝐢𝐩 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐒𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐠 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬. 𝐃𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐥 𝐩𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐚𝐦𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐲𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐡.

𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄ 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐠𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐢𝐦𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐠𝐬𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬. 𝐅𝐨𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐝𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐝𝐢𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐧 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐧𝐬. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐝𝐨 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐛𝐨𝐨𝐤𝐬.

𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄ 𝐞𝐦𝐩𝐡𝐚𝐬𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐬𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞. 𝐅𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐥𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝 𝐝𝐮𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐧𝐨 𝐢𝐧𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞. 𝐈𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐬𝐭, 𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄ 𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐖𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐝 𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐝𝐞𝐝 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐜𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐝𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐝 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐟𝐥𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐛𝐲 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐬 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞𝐱 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐮𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐧 𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐞𝐦𝐩𝐢𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐡𝐲𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐛𝐨𝐨𝐤𝐬 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐦𝐨𝐭𝐞.

𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄ 𝐢𝐬 𝐪𝐮𝐢𝐭𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐫. 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐤𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐥𝐞𝐝𝐠𝐞 𝐭𝐨𝐠𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐥𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐝 𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐌𝐮𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐦𝐬, 𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄ 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐬, 𝐤𝐞𝐩𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐤𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐥𝐞𝐝𝐠𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐝 𝐚 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐟𝐮𝐥 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦. 𝐍𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐝𝐨𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧. 𝐀𝐡𝐦𝐚𝐝 𝐃𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐫𝐤𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄’𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐮𝐝𝐞 𝐢𝐭𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟 𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐚𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞.𝟏𝟗

𝐈𝐟 𝐰𝐞 𝐚𝐝𝐨𝐩𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐁𝐢̄𝐫𝐮̄𝐧𝐢̄’𝐬 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐮𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐢𝐪 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐬 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐬𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐜𝐮𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐯𝐞𝐲𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐥𝐢𝐠𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧; 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐚𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐯𝐞𝐲 𝐤𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐥𝐞𝐝𝐠𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐞𝐦𝐛𝐫𝐲𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲 𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞. 𝐁𝐚𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐧 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬, 𝐚 𝐯𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐟 𝐐.𝟖𝟔:𝟕 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐟𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐥𝐲 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐡𝐚𝐩𝐭𝐞𝐫; 𝐭𝐡𝐮𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐬 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐛𝐬, 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐫𝐠𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐬𝐤𝐞𝐥𝐞𝐭𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐬.

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐝 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧:

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐫𝐝 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐒𝐮𝐥𝐛 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫 (𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐚̄𝐲𝐚𝐡) 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐧. 𝐀𝐥-𝐓𝐚𝐫𝐚̄𝐢𝐛 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐚𝐧. 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐚̄𝐭𝐮̄𝐫𝐢̄𝐝𝐢, 𝐚 𝐜𝐥𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐢𝐚𝐧, 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐚𝐫𝐬 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐟𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐠𝐚𝐫𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐐.𝟖𝟔:𝟕. 𝐇𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐫𝐝𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐛𝐮 𝐁𝐚𝐤𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐀𝐬̣𝐚𝐦 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 ‘𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞’ (𝐬̣𝐮𝐥𝐛) 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐞 ‘𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞’ (𝐭𝐚𝐫𝐚̄𝐢𝐛) 𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐮𝐬, {𝐛𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞} 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐧𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐦𝐞𝐧, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐥𝐞 ‘𝐛𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐭𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐞’ 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐧𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐰𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐧.

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐟𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐛𝐲 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐮𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐚𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐐.𝟒:𝟐𝟑 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬, “𝐰𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐲𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐛𝐞𝐠𝐨𝐭𝐭𝐞𝐧 𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬”. 𝐈𝐧 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝: 𝐰𝐚̄ 𝐡̣𝐚𝐥𝐚̄𝐢𝐥𝐮 𝐚𝐛𝐧𝐚̄𝐢𝐤𝐮𝐦 𝐚𝐥-𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐢̄𝐧𝐚 𝐦𝐢𝐧 𝐚𝐬̣𝐥𝐚̄𝐛𝐢𝐤𝐮𝐦. 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐚̄𝐭𝐮̄𝐫𝐢̄𝐝𝐢 𝐬𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐚𝐬̣𝐥𝐚̄𝐛𝐢𝐤𝐮𝐦 𝐢𝐧 𝐐.𝟒:𝟐𝟑, 𝐰𝐡𝐢𝐜𝐡 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐚𝐦𝐞 𝐚𝐬 ‘𝐬̣𝐮𝐥𝐛’ 𝐢𝐧 𝐐.𝟖𝟔:𝟕, 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐬.𝟐𝟎

𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐰 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐞𝐣𝐚𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐨𝐜𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐝𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐬𝐞𝐱𝐮𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐚𝐭 𝐨𝐝𝐝𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞.

𝐃𝐨𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐥𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐨𝐮𝐬 𝐇𝐨𝐥𝐲 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧 𝐌𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐒𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐄𝐠𝐠?

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

𝐍𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐥𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐭 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐫 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐨𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐛𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐨𝐫 𝐜𝐚𝐧𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐭 𝐛𝐲 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐮𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐞𝐮𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐞𝐧𝐬𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐮𝐚𝐥 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐠𝐫𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞.

𝐓𝐡𝐫𝐞𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐜𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐯𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐚𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐫𝐫𝐨𝐫𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐩𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐝𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐧 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐞𝐫𝐚 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐨𝐜𝐢𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐜𝐞𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐝 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐭 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬.

𝐀𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐡 𝐊𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐬 𝐁𝐞𝐬𝐭.

𝐑𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬:

Scientific Qurán Miracles: Backbone and Ribs Quran (86:6-7)

Sex determination from the Quran? Quran (53:45-46)

Human Embryology and the Holy Quran: An Overview

Scientific Qur’an Miracles: Backbone and Ribs

The Scientific Miracles of the Qur’an

Some of the Many Scientific Facts found in the Noble Quran

Astonishing Series of Who Told Prophet Muhammed?

Proof from History of Moon Splitting Into Two

Miraculous Prophet Muhammed Peace be upon him

Scientific Elaboration of Quran (95:4)

Scientific Proof of Barrier Between Sweet and Salt Water Quran (25:53)

Paul the False Apostel of Satan

𝐁𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐚 𝐁𝐚𝐜𝐤𝐁𝐨𝐧𝐞 & 𝐑𝐢𝐛𝐬 𝐇𝐨𝐰 𝐒𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐎𝐛𝐬𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐁𝐞𝐚𝐮𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧

𝐑𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬

𝟏 𝐁𝐚𝐝𝐚𝐰𝐢, 𝐄𝐬𝐚𝐢𝐝 𝐌., 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥 𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦, 𝐌𝐮𝐡𝐚𝐦𝐦𝐚𝐝. (𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟖) 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐔𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞. 𝐁𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐥: 𝐋𝐞𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧, 𝐩. 𝟐𝟓𝟕.

𝟐 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝, 𝐩𝐩. 𝟓𝟑𝟎-𝟓𝟑𝟏.

𝟑 𝐌𝐚̄𝐭𝐮̄𝐫𝐢̄𝐝𝐢, 𝐀𝐥-. (𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟕). 𝐓𝐚𝐰𝐢̄𝐥𝐚̄𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧. 𝐈𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐛𝐮𝐥: 𝐃𝐚̄𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐢̄𝐳𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐯𝐨𝐥. 𝟏𝟕, 𝐩. 𝟏𝟓𝟗.

𝟒 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐔𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐩𝐩. 𝟏𝟓𝟕-𝟏𝟓𝟖.

𝟓 𝐓𝐚𝐰𝐢̄𝐥𝐚̄𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧. 𝐕𝐨𝐥. 𝟏𝟕, 𝐩. 𝟏𝟓𝟗.

𝟔 𝐈𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐮̄𝐧 𝐭̣𝐚̄ 𝐟𝐚̄ (ن ط ف). 𝐈𝐭 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐚 𝐝𝐫𝐨𝐩 𝐨𝐟 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫, 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦. 𝐒𝐞𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐔𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐩. 𝟗𝟒𝟔.

𝟕 𝐈𝐭𝐬 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐦𝐢̄𝐦 𝐰𝐚̄𝐰 𝐡𝐚̄ (م و ه) 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐭 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫, 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝, 𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐢𝐭𝐬 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐮𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞. 𝐒𝐞𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐔𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐩. 𝟗𝟎𝟕. 𝐀𝐥𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐠𝐡 𝐢𝐭 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐥𝐬𝐨 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧 𝐬𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐦, 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐚𝐜𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐬𝐭 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐢𝐬 𝐧𝐮𝐭̣𝐟𝐚𝐭 (نُّطْفَة). 𝐍𝐨𝐭𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐦𝐚̄𝐚 (مَآء) 𝐢𝐬 𝐜𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐫 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐨𝐟 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐢𝐝.

𝟖 𝐒𝐞𝐞 𝐊𝐢𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐳𝐞𝐧𝐛𝐚𝐮𝐦, 𝐋. 𝐀𝐛𝐫𝐚𝐡𝐚𝐦 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐓𝐫𝐞𝐬, 𝐋. 𝐋𝐚𝐮𝐫𝐚. (𝟐𝟎𝟐𝟎) 𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐂𝐞𝐥𝐥 𝐁𝐢𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲: 𝐀𝐧 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐨 𝐏𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐨𝐠𝐲. 𝐅𝐢𝐟𝐭𝐡 𝐄𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧. 𝐄𝐥𝐬𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐞𝐫, 𝐩. 𝟕𝟕𝟏; 𝐡𝐭𝐭𝐩𝐬://𝐰𝐰𝐰.𝐥𝐚𝐛𝐜𝐞.𝐜𝐨𝐦/𝐬𝐩𝐠𝟔𝟐𝟖𝟏𝟔𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐨𝐟_𝐬𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧.𝐚𝐬𝐩𝐱.

𝟗 𝐈𝐛𝐧 ‘𝐀𝐭𝐭𝐢𝐲𝐚 𝐀𝐥-𝐀𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢. (𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟏). 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐮𝐡̣𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐚𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐖𝐚𝐣𝐢̄𝐳 𝐅𝐢̄ 𝐓𝐚𝐟𝐬𝐢𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐊𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐛 𝐀𝐥-‘𝐀𝐳𝐢𝐳. 𝐁𝐞𝐢𝐫𝐮𝐭: 𝐃𝐚̄𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐊𝐮𝐭𝐮𝐛 𝐀𝐥-‘𝐈𝐥𝐦𝐢𝐲𝐲𝐚, 𝐯𝐨𝐥. 𝟓, 𝐩. 𝟒𝟔𝟓; 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐭𝐮𝐛𝐢., 𝐀𝐥-. (𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟔). 𝐀𝐥-𝐉𝐚̄𝐦𝐢’ 𝐋𝐢 𝐀𝐡̣𝐤𝐚̄𝐦 𝐀𝐥-𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧. 𝐁𝐞𝐢𝐫𝐮𝐭: 𝐌𝐮𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐬𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐑𝐢𝐬𝐚̄𝐥𝐚, 𝐯𝐨𝐥. 𝟐𝟐, 𝐩. 𝟐𝟏𝟎.

𝟏𝟎 𝐀𝐛𝐝𝐞𝐥-𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐞𝐦, 𝐌. (𝟐𝟎𝟏𝟕). 𝐄𝐱𝐩𝐥𝐨𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧: 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐱𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐜𝐭. 𝐋𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐨𝐧: 𝐈.𝐁. 𝐓𝐚𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐬, 𝐩. 𝟏𝟗𝟏.

𝟏𝟏 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝.

𝟏𝟐 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝; 𝐞.𝐠. 𝐐.𝟐𝟐:𝟓; 𝐐.𝟐𝟑: 𝟏𝟐-𝟏𝟒.

𝟏𝟑 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝; 𝐞.𝐠. 𝐐.𝟕𝟖:𝟏𝟓; 𝐐.𝟒𝟎:𝟔𝟕; 𝐐.𝟓𝟎:𝟏𝟏.

𝟏𝟒 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜-𝐄𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐡 𝐃𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐜 𝐔𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐞, 𝐩. 𝟐𝟓𝟕.

𝟏𝟓 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝.

𝟏𝟔 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝.

𝟏𝟕 𝐈𝐛𝐢𝐝; 𝐞.𝐠. 𝐐. 𝟒𝟖:𝟖-𝟗.

𝟏𝟖 𝐌𝐚𝐤𝐤𝐢, 𝐌. 𝐀. (𝟐𝟎𝟏𝟎). 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐮’𝐢̄𝐧 ‘𝐀𝐥𝐚 𝐓𝐚𝐝𝐚𝐛𝐛𝐮𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐊𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐛 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐮𝐛𝐢̄𝐧. 𝐁𝐞𝐢𝐫𝐮𝐭: 𝐌𝐮𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐬𝐚𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐑𝐚𝐲𝐲𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐩. 𝟓𝟗𝟏.

𝟏𝟗 𝐃𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐥, 𝐀. (𝟐𝟎𝟏𝟎). 𝐈𝐬𝐥𝐚𝐦, 𝐒𝐜𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐡𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐧𝐠𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐇𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲. 𝐘𝐚𝐥𝐞 𝐔𝐧𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬, 𝐩𝐩. 𝟏𝟏𝟒-𝟓.

𝟐𝟎 𝐌𝐚̄𝐭𝐮̄𝐫𝐢̄𝐝𝐢, 𝐀𝐥-. (𝟐𝟎𝟎𝟕). 𝐓𝐚𝐰𝐢̄𝐥𝐚̄𝐭 𝐀𝐥-𝐐𝐮𝐫𝐚𝐧. 𝐈𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐛𝐮𝐥: 𝐃𝐚̄𝐫 𝐀𝐥-𝐌𝐢̄𝐳𝐚̄𝐧, 𝐯𝐨𝐥. 𝟏𝟕, 𝐩. 𝟏𝟓𝟗.

𝐒𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐜𝐞: 𝐒𝐚𝐩𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐈𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐮𝐭𝐞