𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐬𝐞 𝐋𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐎𝐟 𝐀𝐫𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐜 𝐌𝐚𝐧𝐮𝐬𝐜𝐫𝐢𝐩𝐭𝐬 𝐎𝐟 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐐𝐮𝐫’𝐚̄𝐧 𝐀𝐭𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐛𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐓𝐨 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐅𝐢𝐫𝐬𝐭 𝐂𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐲 𝐇𝐢𝐣𝐫𝐚

1. Introduction

Accurately dating early Qur’anic manuscripts is a difficult task.[1] There is only one dated manuscript of the Qur’an from the 1st century of hijra[2] and two from the 2nd century, forcing specialists to look elsewhere for comparative material. Dated Arabic papyri and inscriptions from the 1st century of hijra are fairly abundant and thus serve a useful task in providing a basis of comparison with those Qur’anic manuscripts written in the so-called ḥijāzī and kufic styles.

Around fifty years ago, Adolf Grohmann was one of the first scholars to specifically list those Arabic manuscripts of the Qur’an attributable to the 1st century of hijra.[3] His list comprised of British Museum Ms. Or. 2165, Arabe 328a, Istanbul Topkapi Saray Medina 1a, A. Perg. 2, P. Cair. B. E. 1700, Vat. Ar. 1605, Arabic Pal. Pl. 44 and P. Michaélidès No. 32. The main basis for Grohmann’s dating was palaeographical via comparisons with early dated Arabic papyri.

Around thirty five years later, Gruendler compiled all the published dated Arabic texts from the 1st century hijra known to her, in which she briefly discussed early manuscripts of the Qur’an. To Grohmann’s list of eight manuscripts (actually seven distinct manuscripts) Gruendler added three more, namely, Ms. Or. 1287 (‘Mingana Palimpsest’), DAM 01-27.1 (belongs to Codex Ṣanʿāʾ I) and LNS 19 CAab (belongs to Ms. Or. 2165).[4]

One of the most recent lists of 1st century manuscripts of the Qur’an has been adduced by Noseda and is not based on Grohmann’s list nor Grohmann’s list as amended by Gruendler. Noseda and Déroche produced a table of ḥijāzī manuscripts of the Qur’an that were known to them,[5]

And, according to Noseda, solely from the 1st century of hijra.[6] Noseda compared the contents of the Qur’an in the ḥijāzī manuscripts with the equivalent pages of the so-called King Fuʾād edition, and remarkably, was able to conclude that 83% of the entire Qur’anic text was represented in these manuscripts.[7]

The tables provided by Noseda contain only the barest of details. Primarily, only the holding institutions are mentioned and not the actual manuscripts themselves, neither are the exact contents given. Noseda used a combination of dashes to indicate how much of a particular Qur’anic sūrah is present; there are no bibliographic details whatsoever.

With Grohmann’s list as amended by Gruendler and Noseda’s tables as a starting point, we wish to provide additional information as well as mentioning some more folios and manuscripts which have recently come to light or that were not known or originally considered by them.

Why the first century hijra? It goes without saying this is the earliest and consequently the most important period of Qur’anic manuscript production, that gives us the biggest insight into the text and its transmission. There will always be a level of arbitrariness in choosing a terminus date. The end of the first century of hijra hastens many significant milestones in the visual culture of the early Muslims.

To name but a few, the promulgation of Arabic as the official script and language of the chancery, the establishment of monumental building projects and copies of the Qur’an produced directly and indirectly under official patronage.

The aim of this article is modest. It is to present an up-to-date and accurate list of Arabic manuscripts of the Qur’an that are attributable to the 1st century of hijra along with full bibliographic references so that the interested reader may acquire additional information.

Only manuscripts of the Qur’an are given consideration here. Qur’anic inscriptions on rocks, coins and other materials from the 1st century of hijra are not included and have been given elsewhere. In many ways, this is a working document, as the information presented in this document would be updated as more manuscripts are published in the scholarly literature.

2. Identification Of Early Qur’anic Manuscripts: Status Quaestionis

Assessing early Qur’anic manuscripts can be a rather daunting task when one considers the relevant technicalities that need to be addressed. For instance, the physical format and dimensions of the page, the margins and ruling, the specific shape of certain letters of the Arabic alphabet in their various forms, letter/word spacing, verse counting/numbering systems, verse and chapter separators, illumination if present, radiocarbon dates, orthographic peculiarities, regional, multiple and variant readings, and even the type and colour of ink used.

Thus a considerable amount of data, much of which can only be verified by a firsthand inspection of the manuscript, needs to be carefully examined before one can start to consider an early dating. With this in mind, the dating of early Qur’anic manuscripts is the reserve of a limited number of specialists worldwide.

It is oft-repeated that the only reliable way of dating Qur’anic manuscripts is with the presence of an endowment notice. Some scholars suggest that without this potentially reliable piece of evidence it is not possible to safely date Qur’an manuscripts to an early period. This, however, is an unreasonable standard.

To think that with the discovery of a single folio of the Qur’an in the ḥijāzī style that is most likely only partially preserved, one should expect to find a perfectly preserved endowment notice is quite unreasonable. Scholars have relied on various evidences and techniques to date the early manuscripts of the Qur’an. We will describe some of them briefly.[8]

LITERARY EVIDENCE AND SOME NEW CONSIDERATIONS

In terms of the literary identification of the earliest Arabic script, scholars have had to make do with the slender description provided by the Baghdadi Shi’ite bookseller and bibliographer Abū l-Faraj Muḥammad bin Isḥāq Ibn al-Nadīm (d. 380 AH / 990 CE). He said,

Thus saith Muḥammad ibn Ishaq [al-Nadīm]: The first of the Arabic scripts was the script of Makkah, the next of al-Madīnah, then of al-Baṣrah, and then of al-Kūfah. For the alifs of the scripts of Makkah and al-Madīnah there is a turning of the hand to the right and lengthening of the strokes, one form having a slight slant.[9]

A similar interpretation of the second sentence was also advocated by Abbott. A better and probably more accurate rendering of the second sentence is given by Blair from an unpublished article which Whelan had just completed before her death titled, ‘The Phantom Of Ḥijazi Script: A Note On Paleographic Method’.

In their alifs [of the scripts of Makkah and al-Madīnah] there is a turning of the hand to the right and an elevation of the ascenders, and in their form a slight incline.[10]

Based on an interpretation of this text such as is given by Abbott and in Dodge’s translation, the three criterion mentioned above have usually been taken to refer to the alifs only. Based on grammatical observations, however, all three criterion can be applied to aspects of the script in general.

Thus, based on Whelan’s interpretation, the criterion should be properly understood as follows:

- alifs which turn to the right,

- elevated ascenders, and

- slightly inclined form.

After describing the earliest Arabic script of Makkah and Madinah, al-Nadīm goes on to describe the earliest Qur’anic scripts which Déroche and Noseda quite sensibly consider to be identical to those that he lists in the equivalent scripts of Makkah and Madinah.

With al-Nadīm’s information one is unable to differentiate between the script of Makkah and Madinah, hence the rubric ‘ḥijāzī’ a common geographical area in North-West Arabia including Makkah and Madinah[11] that functions as a catch-all label for the earliest script. Thus, on the basis of these three pieces of data, scholars have come to identify the so-called ḥijāzī style of writing the Qur’an as meeting these requirements.

It should be recognised this is but one small strand of a mountain of literary evidence whose great potential still awaits systematic exploration, investigation and integration in relation to the extant manuscript evidence. The first century hijra witnessed the introduction and use of diacritical signs to distinguish similar looking consonants, vocalisation, special signs marking the division of the Qur’an into sections, statistical counting of letters, words.

And verses and the separation of surahs – advances pioneered by the early Muslims with the aim of eliminating the faults present amongst some in the speaking, reading and writing of the Qur’an, as well as proving the Qur’an’s veracity. We now know with ever greater detail the actors involved in these events, and the time periods when these improvements were accomplished.[12]

By relating these advances in the Arabic script used to pen the Qur’an and the various visual techniques to enhance and aid readability and presentation, in conjunction with the modern techniques related in this section, we could perhaps arrive at a more reliable way of dating early Qur’an manuscripts.

For example, consider the following description of the early Qur’anic manuscripts in the literary sources that when probed provides some solid chronological data. Abū Naṣr Yaḥya ibn Abī Kathīr al-Yamāmī (d. 132 AH / 749 CE) a traditionalist and narrator of ḥadīth from several of the Prophet’s companions, provides a very important piece of chronological data specifically with regard to the earliest Qur’anic manuscripts. Recently brought to notice by al-A‘zami, this datum has gone unnoticed in western scholarship. He said,

The Qur’an was kept free [of dots, marks, and so on] in muṣḥaf. The first thing people have introduced in it is the dotting at the letter bā (ﺏ) and the letter tā (ﺕ), maintaining that there is no sin in this, for this illuminates the Qur’an.

After this people have introduced big dots at the end of verses, maintaining that there is no sin in this, for by this the beginning of a verse can be known. After this people introduced marks showing the ends of sūrahs (khawātīm) and marks showing their beginnings (fawāṭiḥ).[13]

A truncated version of the above statement can be found in Ibn Kathir’s Tafsīr al-Qur’ān, in the section fada’il al-Qur’an,

Dots were the first thing incorporated by Muslims into the muṣḥaf, an act which they said brought light to the text [i.e., clarified it]. Subsequently they added dots at the end of each verse to separate it from the next, and after that, information showing the beginning and end of each sūra.[14]

It is therefore clear that adding dots/marks to the muṣḥaf was one of the earliest undertakings in order to clarify the text.[15] What makes this statement critically important is that it must have been a near contemporaneous observation; we do not know at what point during his life he made this statement but one may assume it was during his scholarly lifetime, sometime in the late 1st, early 2nd century of hijra. Could this be a polemical or dogmatic statement ascribed to the mouth of Abū Naṣr? Being a piece of incidental information, at first sight, it would not seem to serve any dogmatic purpose.

Admittedly, there were debates in the 1st / 2nd centuries hijra regarding the use of dots in early Qur’anic manuscripts, be they something that were disliked or recommended. Could the statement made by Abū Naṣr have been ascribed to him later on by someone wishing to advance their side of the debate?

It would seem not. The debate over dotting started in the 1st century hijra and reached its peak during the 2nd century.

If one reads Abū Naṣr’s statement carefully it becomes apparent he is not advocating a particular viewpoint, neither does he criticise the alternative viewpoint. His statement simply conveys a factual observation, thus lending credence to the fact he actually uttered these words.

As there is no evidence to suggest otherwise, it seems safe to assign this statement to the mouth of Abū Naṣr around the late first, early second century of hijra with a terminus ad quem of 132 AH / 749 CE.

Based on Abū Naṣr’s observations we have a tentative relative chronology of textual aids as follows:

- manuscripts without diacritical marks, dots to separate verses or indication of the beginning/ending of a sūrah,

- manuscripts with diacritical marks, no dots to separate verses and no indication of the beginning/ending of a sūrah,

- manuscripts with diacritical marks, dots to separate verses and no indication of the beginning/ending of a sūrah, followed by

- manuscripts with diacritical marks, dots to separate verses and indication of the beginning/ending of a sūrah.

Abū Naṣr’s statements give no indication how much time elapsed between these four different stages, but they were obviously important enough for him to draw a distinction between them which must have been recognisable not only to him but to other scholars of that period.

This of course does not mean one can simply lump early Qur’anic manuscripts into these four categories in order to sort them chronologically as there would have necessarily been some overlap between these groups; additionally, the tendency towards conservative writing traditions is well known in the Qur’anic manuscript tradition.

What this information does allow one to do is to conceptualise the formation of the Qur’anic manuscript tradition within a general chronological framework.

With the importance of this datum established, how does Abū Naṣr’s statement relate to those manuscripts listed in the table below? All of the early ḥijāzī and kufic style manuscripts listed there have sparse diacritical marks and a combination of dots or dashes variously arranged to (sometimes only occasionally) indicate the end/beginning of verses.

It would appear the very earliest Qur’an manuscripts, stages I and II according to the classification given above, probably those written during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad and shortly thereafter, do not seem to have survived or have yet to be discovered. Thus, this datum serves to further solidify the antiquity of ḥijāzī style manuscripts and corroborates the literary description of the earliest Arabic script described by al-Nadīm.

PALAEOGRAPHIC AND CODICOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

In cataloguing the Qur’anic manuscripts kept in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Déroche created a typology of the Qur’anic script, the earliest which were those in ḥijāzī style in which he identified four principle varieties of writing; he named these Ḥijāzī I, II, III and IV, and provided a brief set of criteria which sets out the means by which one can identify the script according to his method.[16] Later on using the same method, Déroche categorised the early Qur’an manuscripts kept in the Nasser David Khalili collection.

Importantly, he mentioned that ḥijāzī manuscripts were certainly produced in the 1st century hijra continuing into the early 2nd century of hijra, gradually dissipating due to the prominence given to the so-called kufic script under the institutional reforms of ʿAbd al-Malik. He also clarified that his categories were not to be understood as implying strict chronological development, and that they were subject to change and modification dependant on new discoveries or developments.

One problem with Déroche’s method is that it is nowhere clear whether the small and sometimes minute variations between the various styles he has identified, are differences in script or simply regional variations or just different scribal practices. Also, his use of letters appeals to the taxonomist but has little meaning when placed into its proper historical context, creating a classification system apart from the Qur’anic manuscript tradition.[17]

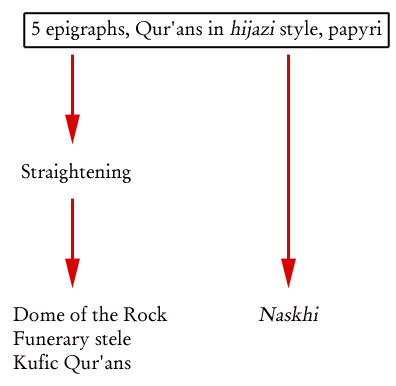

Based primarily on the literary description of al-Nadīm combined with modern investigations into the earliest Qur’anic manuscripts, Noseda presented a ‘new’ diagram of the development of Arabic palaeography.[18]

Noseda gives no guidance on how one should interpret his diagram. However it is clear that he believes with the emergence of the kufic script as it appeared during the time of caliph ʿAbd al-Malik, the ḥijāzī script slowly gave way to its new successor. Thus largely on palaeographic grounds, scholars now believe the bulk of the ḥijāzī corpus is located in the 7th century CE.[19] Straightening in the epigraphic inscriptions only begins in the sixth decade of hijra with kufic proper not making an appearance until the caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik.

It is partly on this basis that Noseda, Déroche and others dated Qur’ans in the ḥijāzī style to the 1st century of hijra and it is the method used by Noseda in identifying the Qur’anic manuscripts in their table as coming from the 1st century of hijra.

Whereas palaeography in a broad sense refers to the study of ancient writing systems, codicology “refers primarily to the study of the material aspects of codices …”[20] With just a handful of exceptions extant,[21] the writing surface on which the earliest (and subsequent) Qur’anic manuscripts were written was on parchment. The form of the early Qur’anic manuscripts is the classic codex format.

Although there are a few examples of early Qur’ans utilising the rotulus scroll format,[22] it would appear Muslim scribes never used the volumen scroll format, whereby the layout of the lines is perpendicular to the axis with the text arranged in columns.

The way by which the early Qur’anic codex itself was physically brought together is still a largely unexplored item. As will soon become apparent, few of the earliest ḥijāzī style Qur’anic manuscripts contain a continuous sequence of folios, which is essential in understanding how the parchment was used to make up quires.

Based on a survey of two large collections located at the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, and Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi, Istanbul, Déroche has shown from the late first until 4th century of hijra, the vast majority of Qur’anic manuscripts are composed of quinions, i.e., quires of ten folios. However, this cannot be taken as a generalisation.

For example, whilst Arabe 328c from the second half of the 1st century hijra, is composed of quinions, Arabe 328a, also from the same time period, is composed of quaternions, i.e., quires of eight folios. The use of coloured inks in early Qur’anic manuscripts can be traced to the 1st century of hijra. Before the emergence of Islam, red ink was used for highlighting certain elements of a given text, such as titles and the like.

We can observe a few examples in the table below. Is 1615 I and Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572a (= Arabe 328c) contain sūrah separators penned in red ink in the form of a basic geometric pattern. Ms. Or. 2165 contains surah headings in red ink although these appear to have been added at a later date.

Coloured inks were even used to highlight a specific page layout. TIEM ŞE 362 from the late first to early 2nd century hijra uses three contrasting colours to create an observable geometric pattern in the text, likewise TIEM ŞE 12995 from the beginning of the 2nd century hijra.

These examples are given to show the complex methods executed by early Muslim scribes and to dismiss the notion held by some that a Qur’anic manuscript showing any form of illumination/decoration cannot possibly be considered an early production. There are of course many other codicological considerations and we have only mentioned a few thought to be particularly relevant to the present study.[23]

Art history is the academic study of objects of art in their historical development and stylistic contexts and involves a study of genre, design, format, and look. Therefore, an art historian uses the historical method to answer foundational questions

Such as how did the artist come to create the work, who were his or her teachers, who was the audience, who were the patrons, what historical forces fashioned the artist’s work and in turn how did it affect the course of artistic, political or social events. Studies by art historians often involve close scrutiny of individual objects.

Using them, they attempt to answer in historically specific ways, questions such as what are the key features of its style, what symbols are involved, to which period can the object be dated, what meaning did this object convey, how does it function visually, and so on.

One of the best examples from the Qur’anic manuscripts studied using the art-historical method isDAM 20-33.1. The decorative elements of this lavishly illustrated manuscript have been compared with dated and datable buildings from the Umayyad era, most notably the Dome of the Rock, the Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ,

The Great Mosque of Damascus and the façades, niches and associated mosaics of various other building structures. The fine geometric, architectural and vegetal patterns calligraphed on this manuscript bear a striking resemblance and share certain stylistic idiosyncrasies pointing towards a similar timeframe of production.[24]

By studying the palaeography, ornamentation and illumination of this manuscript, Hans-Caspar Graf von Bothmer dated it to the last decade of the 1st century of hijra, around 710–715 CE, in the reign of the Umayyad caliph al-Walīd.[25] Similarly,

Déroche arrived at the 1st century hijra dating of TIEM ŞE 321 (located at Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi, Istanbul) by studying illumination, script, the 10-bifolio quire structure and the direct relation of the ornaments used in the manuscript with the mosaics at the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. He dates it to the time after 72 AH / 691–692 CE or more probably during the last quarter of the 1st (early 8th) century hijra.[26]

Early Islamic “art” is becoming increasingly well studied and recent specialised publications are now giving an even clearer picture of Umayyad tendencies.[27] Some scholars have criticised this method of dating due to its suspected circularity as no wider art-historical samples for comparison beyond the Umayyad era are taken into consideration. It is thus argued the date assigned to a given manuscript using this method is the same time frame from where comparative material is normally adduced.[28]

SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE (RADIOCARBON DATING)

In recent years, a highly promising scientific method of dating Qur’an manuscripts has been utilised, namely, radiocarbon dating. One of the great benefits and advantages of this method of dating is that scholarly prejudice and pre-suppositions about the genesis of Arabic scripts and Qur’anic manuscripts are not factored into the calculation.

Nevertheless, one of the downsides is the large time intervals which do not prove very useful in dating manuscripts very precisely. Some examples are manuscript St. Petersburg E20 and the Samarqand manuscript, both of which are falsely attributed to ʿUthmān.

They both have large ranges of 225 and 260 years, respectively. Such is not always the case. To give a recent example, Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572a has been radiocarbon dated at the University of Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit to the 6/7th century CE with an overall time interval of 77 years.

The 95.4% confidence level yields a timeframe of 568–645 CE – reaching into the first 23 years of hijra – making this a highly useful result.

Radiocarbon dating has been put to the test by comparing its results with art historical methods with regard to the dating of Roman and Coptic textiles; the authors conclude that radiocarbon dating can assist the art-historical method and is not something to be frowned upon or feared.[29]

To our knowledge, nineteen Qur’anic manuscripts have been successfully dated using this method. Eight of them form part of the table below.

Armed with the above-mentioned methods employed for dating Qur’anic manuscripts, especially in light of new documentary evidence, it should no longer be controversial to consider the vast majority of ḥijāzī Qur’ans as belonging to the 1st century of hijra. George says,

The oldest manuscripts of the Qur’an – called ‘Hijazi’ in modern scholarship, even though many of them were probably not made in the Hijaz – are key witnesses in the genesis of Arabic calligraphy. Their date has been a subject of controversy in modern scholarship.

But thanks to the discovery of new documents from the first decades of Islam and to our better understanding of the transformation of Arabic script under the Umayyads, it is becoming increasingly clear that the vast majority of these Qur’ans were written in the first century of Islam.[30]

Bearing this in mind, let us now tabulate the manuscripts datable to 1st century of hijra using the methods described above and in combination with each other. It is of course entirely possible, even probable, that some of the manuscripts listed below may extend to the early second century of hijra.

3. Ḥijāzī & Kufic Manuscripts Of The Qur’ān From 1st Century Of Hijra Present In Various Collections

The table below lists the ḥijāzī and kufic Qur’anic manuscripts from the 1st century hijra present in various collections around the world. This list is certainly not authoritative and omits manuscripts which are known to be present in collections but their accession number, folios and content are not known. The table entries are not ordered chronologically; instead, manuscripts that are written in a similar script style have been grouped together for ease of navigation.

| Designation / Inv. No. | Medium | Format | Size (cms) | Script | Lines per page | Folios | Contents (representative sūrahs) | Carbon-dating | ʿUthmānic | Qirā’āt | Déroche’s Typology | Provenance | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabe 328a[31]Marcel 18/1[32]Arabe 328b[33]Vaticani Arabi 1605[34]KFQ60[35] | Parchment | Vertical | 33 x 24 | Ḥijāzī | 21–28 | 56261411 | 2-15; 23-28; 30-31; 35; 38-39; 41-46; 56-57; 60-63; 65-67; 69-72 | No | Yes | Ibn Āmir | HI | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; National Library of Russia, St Petersburg; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City; Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London. |

| Arabe 328c[36]M. 1572a (ff. 1, 7)[37] | Parchment | Vertical | 33.5 x 25.3 | Ḥijāzī | 23–25 | 162 | 10-11, 20-23; 18-20 | Yes: 568-645 CE, 95.4% confidence level. | Yes | – | HI | Egypt? | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. |

| Arabe 6140a[38]Ms. Add. 1125[39] | Parchment | Vertical | 37.5 x 28.0 | Ḥijāzī | 22–25 | 42 | 7-9 | No | Yes | – | HI | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; University Library, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. |

| Marcel 19[40]Arabe 328f[41] | Parchment | Vertical | 29.0 x 25.0 | Ḥijāzī | 20 | 132 | 18-19; 23-26; 28 | No | Yes | – | HI | – | National Library of Russia, St Petersburg; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| TIEM ŞE 54[42] | Parchment | Vertical | 37 x 28 | Ḥijāzī | 24 | 11+ | 14-15 | No | Yes | – | HI | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 86[43] | Parchment | Vertical | – | Ḥijāzī | 24 | 1 | 31 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 87[44] | Parchment | Vertical | 38.0 x 29.0 | Ḥijāzī | 22 | 2 | 60-63 | No | Yes | – | – | Syria? | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 118[45] | Parchment | Vertical | 31 x 24 | Ḥijāzī | 21-26 | 16 | 25 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 3687[46] | Parchment | Vertical | 24 x 16 | Ḥijāzī | 22-29 | 10 | 66-67 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 13316/1[47] | Parchment | Vertical | 24 x 17 | Ḥijāzī | 18-22 | 15 | 21 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 13884[48] | Parchment | Vertical | – | Ḥijāzī | 23-24 | 2 | 40 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| DAM 01-25.1[49] | Parchment | Vertical | 33.5 x 26 | Ḥijāzī | 21–27 | 29 | 1-2; 7-8; 10-11; 17-20; 24; 26; 33; 39; 41-46 | Yes: 543-643 CE, 95.4% confidence level. | Yes | – | – | – | Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. |

| AMAS[50]DAM 01-27.1[51]Sotheby’s 1992, Lot 551 / David 86/2003 (=Sam Fogg IAGIC)[52]Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 31 / Stanford 2007[53]Bonham’s 2000, Lot 19[54]Christies 2008, Lot 20[55]Louvre Abu Dhabi | Parchment + Palimpsest | Vertical | 37 x 28 | Ḥijāzī | 19–37 | 403611111 | 2-12; 14-22; 25-35; 37-39; 41-44; 47-48; 55-60 (does not include scriptio inferior) | Yes: 578 – 669 CE, 95% confidence level.[56] | Scriptio superior – YesScriptio inferior – No | – | – | Western Arabia or Syria | Al-Maktaba al-Sharqiyya, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen; Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen; David Collection, Copenhagen; Private collections; Louvre Abu Dhabi. |

| A. Perg. 2[57] | Parchment | Vertical | 23.7 x 20.5 | Ḥijāzī | – | 1 | 28 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria. |

| P. Michaélidès No. 32[58] | Papyrus | Vertical | 14.8 x 5.9 | Ḥijāzī | – | 1 | 54-55 | No | Yes | – | – | Egypt? | University Library, Cambridge (presently lost). |

| P. Cair. B. E. Inv. No. 1700[59] | Parchment | Vertical | – | Ḥijāzī | 19 (incomplete) | 1 | 25 | No | Yes | – | – | Egypt | Dār al-Kutub al-Misriyya, Cairo. |

| Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 11, 15[60] | Parchment | Oblong | 9.8 x 18.9 | Ḥijāzī | 15 | 2 | 25; 27-28 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Private collection. |

| DAM 01-18.3[61] | Parchment | Oblong | 9 x 19 | Ḥijāzī | 12 | 1 | 8 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. |

| DAM 01-18.9[62] | Parchment | Oblong | 14 x 20 | Ḥijāzī | 16-19 | 4 | 2-3; 8-10 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. |

| DAM 01-20.4[63] | Parchment | Oblong | 13 x 21 | Ḥijāzī | 19-26 | 4 | 9; 11-12 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. |

| TIEM ŞE 3702 b[64] | Parchment | Oblong | – | Ḥijāzī | 13 | 1+ | 44 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 9052[65] | Parchment | Oblong | 9 x 15.7 | Ḥijāzī | 11 | 1+ | 5 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 12827/1[66] | Parchment | Oblong | 15.3 x 21 | Ḥijāzī | 12 | 1+ | 3-4 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| Arabe 7191[67] | Parchment | (Oblong) | (14.5 x 21) | Ḥijāzī | 9-15 | 1 | 5 | No | Yes | – | HI | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| Arabe 7193[68] | Parchment | (Oblong) | (14.5 x 16) | Ḥijāzī | (7-8) | 2 | 5; 20 | No | Yes | – | HI; HII | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| A. Perg. 213[69] | Parchment | Oblong | 16.0 x 24.8 | Ḥijāzī | 16 | 2 | 51-53 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria. |

| A. 6988[70] | Parchment | Oblong | (15 x 22) | Ḥijāzī | 12 | 1 | 48-49 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Oriental Institute, University of Chicago. |

| E. 16269 D[71] | Parchment | Oblong | 16.5 x (30) | Ḥijāzī | 13 | 1 | 37-38 | No | Yes | – | HI | Egypt? | University of Pennsylvania Museum. |

| Ms. Or. 2165[72]Arabe 328e[73]LNS 19 CAab (LNS 63 MS e)[74] | Parchment | Vertical | 31.5 x 21.5 | Ḥijāzī | 21–27 | 12162 | 5-43 | No | Yes | Ḥimsi | HII | Egypt | British Library, London; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait National Museum. |

| Ms. Qāf 47 (includes Arabic Palaeography Pl. 44[75])Ms. Or. Fol. 4313[76] | Parchment | Vertical | 39.3 x 26.2 | Ḥijāzī | 17-21 | 317 | 4-6; 8-11; 14-15; 21; 63-64 | Yes: 606-652 CE, 95.4% confidence level. | Yes | – | HII | Egypt? | Dār al-Kutub al-Misriyya, Cairo; Staatsbibliothek Zu Berlin, Germany. |

| Is. 1615 I[77]Ms. 68, 69, 70, 699.2007[78]Sotheby’s 2008, Lot 3 (= Ms. 699.2007)[79]TR:490-2007[80] | Parchment | Vertical | 36 x 27 | Ḥijāzī | 21–24 | 321411 | 13-16; 28-48[81] | No | Yes | – | Unclassified | Arabian Peninsula? | Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Ireland; Museum Of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar; Vahid Kooros private collection. |

| Arabe 330g[82]Marcel 16[83]Rennes Encheres 2011, Lot 151[84]Is. 1615 II[85]Ms. 1611-MKH235[86] | Parchment | Vertical | 36.0 x 28.5 | Ḥijāzī | 18–22 | 2012641 | 3-10; 27-31; 33; 85-110[87] | No | Yes | – | Unclassified | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; National Library of Russia, St Petersburg; Private collection; Chester Beatty Library, Dublin; Beit al-Qur’an, Manama, Bahrain. |

| Arabe 7192[88] | Parchment | (Oblong) | (5.4 x 10.3); (14.8 x 15.3); (5.5 x 13.5) | Ḥijāzī | (24) | 1 | 11-12 | No | Yes | – | Unclassified | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| TIEM ŞE 3591[89] | Parchment | Oblong | – | Kufic | 15 | 1+ | 34 | No | Yes | – | OIa | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| TIEM ŞE 4321[90] | Parchment | Oblong | – | Kufic | 18 | 1+ | 54-55 | No | Yes | – | OIa | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| Marcel 11Marcel 13Marcel 15[91]Arabe 330c[92] | Parchment | Vertical | 37 x 31 | Kufic | 25 | 1242109 | 15-27; 30-41 | No | Yes | – | OIb | Syria? | National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| TIEM ŞE 321[93] | Parchment | Vertical | 24 x 19.5 | Kufic | 18-21 | 78 | 17-54 | No | Yes | – | OIb | Syria? | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| DAM 01-29.1[94] | Parchment | Vertical | 43 x 29.7 | Ḥijāzī | 16–30 | 35 | 2-8; 14-17; 19-22; 33-34; 36-37; 39-40; 42-53; 69-74; 80-89 | Yes: 603-662 CE, 95.4% confidence level. | Yes | – | BIa | – | Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. |

| Arabe 331[95]Marcel 3Ms. Leiden Or. 14.545b + Or. 14.545c[96]A 6959 + A 6990[97]E16264 R | Parchment | Vertical | 41.3 x 34.8 | Ḥijāzī | 19 | 5626221 | 2; 4-9; 11; 14-18; 25-26; 43-60; 63-64; 69-85; 97-100 | Yes: 652-694 CE, 89.3% confidence level. | Yes | – | BIa | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg; University Library, Leiden; Oriental Institute, Chicago; University of Pennsylvania Museum. |

| Marcel 17[98]M. 1572b (ff. 2-6, 8-9)[99]Ms. 67.2007[100] | Parchment | Vertical | 33.5 x 25 | Ḥijāzī | 21–33 | 1874 | 2-4; 4-6; 5-6 | No | Yes | – | BIa | Egypt? | National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg; University of Birmingham, United Kingdom; Museum Of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar. |

| Marcel 18/2[101]Arabe 328d[102] | Parchment | Vertical | 35 x 25 | Ḥijāzī | 23-26 | 203 | 25-32; 42-43 | No | Yes | – | BIa | – | National Library of Russia, St. Petersburg; Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| TIEM ŞE 56[103] | Parchment | Vertical | 39.8 x 27.9 | Ḥijāzī | 27 | 8 | 28-33 | No | Yes | – | BIa | – | Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul. |

| M a VI 165[104] | Parchment | Vertical | 19.5 x 15.3 | Ḥijāzī | 18-21 | 77 | 17-36 | Yes: 649-675 CE, 95.4% confidence level. | Yes | – | BIa | Syria? | Universitäts bibliothek Tübingen, Germany. |

| Sotheby’s, 1993, Lot 34[105] | Parchment | Vertical | 41.0 x 28.6 | Ḥijāzī | 20–27 | 8 | 3 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Private collection. |

| Sotheby’s 2010, Lot 3[106] | Parchment | Vertical | 33.0 x 23.0 | Ḥijāzī | 22 | 1 | 6 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Private collection. |

| Sotheby’s 2011, Lot 1[107] | Parchment | Vertical | 36.0 x 27.0 | Ḥijāzī | 21 | 1 | 12 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Private collection. |

| Christies 2011, Lot 10[108]Christies 2013, Lot 50[109] | Parchment | Vertical | 33.5 x 23.2 | Ḥijāzī | 22 | 11 | 7; 40-41 | No | Yes | – | – | – | Private collections. |

| Arabe 7194[110] | Parchment | (Oblong) | (12.3 x 18.2) | Ḥijāzī | (9) | 1 | 4 | No | Yes | – | BIa; HII | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| Arabe 7195[111] | Parchment | (Oblong) | (14.0 x 25) | Ḥijāzī | (8-9) | 3 | 4-5 | No | Yes | – | BIa | – | Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. |

| DAM 20-33.1[112] | Parchment | Square | (51 x 47) | Kufic | – | 25+ | 1-2; 55-56; 67-69; 74-75; 77; 79; 85; 89-90; 99-100; 110; 114 | Yes: 657-690 CE; 645-690 CE, 95% confidence level (Chemical test: 700-730 CE). | Yes | – | CIa | Syria | Dār al-Makhṭūtāt, Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. |

Table I: Listing of the ḥijāzī and kufic manuscripts of Qur’an from 1st century hijra present in various collections around the world.

A “–” indicates that sufficient information regarding this particular aspect of the manuscript has not yet been published or we are in the process of sourcing this information. In the designation field, if the manuscript has been separated and in the process given different accession numbers, all of them will be listed here, the primary holding institution being mentioned first. Only the maximum preserved size of the surviving folios of the manuscript are mentioned in the dimensions field.

If dimensions are given in brackets this is the estimated original size of the folio. Ms. Or. 1287 (‘Mingana Palimpsest’), which contains some portions of Qur’anic text in its scriptio inferior attributable to the 1st century hijra, has not been included in the table and will be added later.

The minimum and maximum number of lines are taken only from intact folios; a damaged or incomplete folio has not been used to supply the minimum number of lines in manuscripts which contain one or more non-partial folios.

The folios field supplies the number of folios that have been mentioned in the literature. If it is obvious there are more folios belonging to the manuscript, we have added a “+” sign. Where available, bibliographic references are provided that were used to populate the columns with information – this is not intended as a comprehensive bibliography for every manuscript, instead a selection of the primary references

. For sake of convenience, all verse numbering is according to the kufan system as found in the modern printed edition of the Qur’an first published in Egypt in 1924. Given the nature of this list, we welcome any comments, additions or corrections to the information contained in the respective columns. Lastly, the information contained in the columns is based on those folios which have been published or mentioned in the literature.

Lest one forget there are a number of important manuscripts of the Qur’an dated to the 1st, 1st / 2nd and 2nd century of hijra (the ones from 1st century have not been included in the above list yet). Amongst them, one could name the following codices from Tunisia: Ms. R 38,[113] Ms. R 119,[114] and Ms. P 511[115]; from Yemen: DAM 01-28.1, DAM 01-18.3, DAM 01-30.1, DAM 01-32.1, DAM 01-29.2 and DAM 01-32.2;[116] from Turkey: Topkapı Sarayı Medina 1a / TSM M1,[117] TIEM Env. 51, 53[118] + Ms. 678[119] + Sam Fogg IAGIC[120] + Ghali Adi Fragment (same manuscript),[121] TIEM ŞE 80,[122] TIEM ŞE 85,[123] TIEM ŞE 89,[124] TIEM ŞE 358,[125] TIEM ŞE 364,[126] TIEM ŞE 709[127] and TIEM ŞE 12995 and numerous other Qur’ans written in an Umayyad script;[128] from Austria: A. Perg. 186, A. Perg 202, and Mixt. 917; from the USA: AL-17 + `Ayn 444 (same manuscript),[129] 1-85-154.101[130] and P. Garrett Coll. 1139;[131] from Egypt: Arabic Palaeography Plates 39-40 + Mss. Arab 21-25 + Arabe 330d + KFQ42 + KFQ62 (same manuscript);[132] from Britain: BL Add. 11737/1[133] and numerous manuscripts from the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art;[134] from France: numerous manuscripts[135] such as Arabe 330a + Ms. 66[136]; from Ireland: Is. 1404 + Arabic Palaeography Plates 19-30 (same manuscript);[137] from the National Library of Russia, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, and the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art: Codex Amrensis 1.[138]

To this list one can also add numerous Qur’ans sold at auction such as Sotheby’s 15th October 1984, Lot 206,[139] Sotheby’s 22nd May 1986, Lot 269,[140] Sotheby’s 30th April 1992, Lots 318 & 319,[141] Sotheby’s 28th April 1993, Lot 73,[142] Sotheby’s 22nd October 1993, Lot 11, 15, 28 & 29,[143] Sotheby’s 19th October 1994, Lot 16,[144] Sotheby’s 24th April 1996, Lot 1,[145] Sotheby’s 16th October 1996, Lot 1,[146] Sotheby’s 15th October 1997, Lot 12,[147] Sotheby’s 13th April 2000, Lot 1,[148] Sotheby’s 3rd May 2001, Lot 8,[149] Sotheby’s 5th October 2011, Lot 47[150] and Sotheby’s 3rd October 2012, Lot 11.[151]

The list can be further expanded by adding at least six Qur’ans popularly attributed to ʿUthmān,[152] found in Samarqand, Russia, two in Istanbul (Topkapi Library and TIEM), and two in Cairo (al-Hussein mosque and Dār al-Kutub);[153] also one Qur’an popularly attributed to the fourth caliph ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib, found in Ṣanʿāʾ. A hitherto largely unknown Qur’anic manuscript, Kodex Wetzstein II 1913 located at the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin,[154] must rank as one of the most significant manuscripts of the Qur’an in a Western institution that still awaits detailed study.

The importance of this manuscript is guaranteed by the remarkably large number of extant folios; in total there are 210 extant folios meaning some 420 pages of examinable text. Similarly, a substantial ḥijāzī codex comprising 270 folios has been redisplayed in the newly renovated Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo. Apart from a brief mention by Gerd-R. Puin[155] and some Moroccan scholars,[156] this manuscript has barely managed a notice.

‘CERTAINTY’ AND THE BURDEN OF PROOF

It is normal scholarly procedure to be cautious but as one moves further toward what one could term as ‘extreme’ caution, it can cause more problems than it claims to solve. For example Arberry dated the Chester Beatty Library manuscript Is. 1615 I to the 4th century hijra / 10th century CE. He called his dating cautious and ‘conservative’.[157] Arberry was, of course, writing at a time when dating Qur’anic manuscripts was much less developed.

However, one cannot simply attach a date to a manuscript and subsequently append the label ‘conservative’ to it. Dating manuscripts is not based on conservatism or liberalism, it is simply trying to assign an accurate date as possible to its production.

Therefore, a Qur’anic manuscript assigned a 4th century date instead of a 1st century date, can do just as much damage to the chronology of the Arabic script as can a manuscript dated to the 1st century that belongs to the 4th. Both dates are inaccurate and injure the chronological time frame resulting in the faulty dating of other manuscripts also. In a similar vein, Blair states that there is no absolute method for dating Qur’anic manuscripts before the 9th century CE / 3rd century hijra.[158]

This observation is correct and is not in doubt, however, one should take care between forming a ‘Pascalian’ certainty of which very few events in antiquity could be verified, to an attribution based on a careful study of the extant documentary evidence in conjunction with relevant historical information. For example, both a palaeographic and radiocarbon analysis give a 1st century hijra date for Mingana Islamic Arabic 1572a.

One could put their hands up in the air and say there is no absolute method to determine that this is the case and it would be quite true. But one should realise that certainty in the field of history in rarely akin to certainty in mathematics, where a conclusion can be demonstrated as an inevitable result of the premises applied.

One could not demonstrate with the same degree of certainty the existence of this manuscript in the 1st century of hijra as one could demonstrate the truth of the Pythagoras theorem. Indeed, if such unjustified epistemological scepticism is advanced to its logical conclusion, centuries of Western Qur’anic scholarship would fall by the wayside with no prospect of a replacement.

Let us consider a somewhat comparable situation in numismatics. The study of Arab-Byzantine coinage from the 7th century, especially the first half of the 1st century of hijra, has been riddled with a certain amount of confusion. Scholars knew the coinage normally associated with this period was very early, but had no secure means by which to attach a specific date to them.

From the wider Islamic conquests beginning in the late 630’s until the reign of ʿAbd al-Malik, there is no coin which has clear internal evidence as to its dating. This has all changed as very recently early Islamic numismatics has seen a methodological breakthrough, whereby secure dates can be attributed to identifiable series of early Arab-Byzantine issues in Syria.[159]

Although provisional, this breakthrough has been adopted by one of the leading scholars in the field of late Roman and Byzantine history, Clive Foss, who utilises the same chronological methodology in his book on Arab-Byzantine coins held in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection.[160]

The earliest Qur’anic manuscripts find themselves in a similar situation today; scholars know they are early but have no generally agreed upon methodology by which to identify them as such. If the breakthrough in the numismatic realm is anything to go by, it shows that promising new research can provide rewarding results.

If one considers the location of these manuscripts, it will become apparent many of them are located in Western institutions. During the nineteenth and twentieth century, Western imperialist and colonial powers had politically, economically, militarily, and culturally dominated the Muslim lands.

Many of the most precious artefacts of these countries were appropriated by officials working in or alongside government and by travelling scholars representing their respective countries’ higher institutions – as the collections of any oriental studies department in the West will attest.

The fruits of such labour can be seen in the works of the German based scholars Gotthelf Bergsträsser and Otto Pretzl, who in their many years of travelling throughout the Muslim lands took approximately 15,000 photographic images amounting to some 450 rolls of film comprising early Qur’anic manuscripts. None of these images were shared with their Muslim hosts.

After the untimely death of both men, Anton Spitaler came to inherit these valuable films, lied about their existence and hid them for more than 50 years before secretly passing them on to his student Angelika Neuwirth who now heads the project Corpus Coranicum.[161]

The announcement regarding the existence of these films was first made known to the ‘general’ public in a cryptic message posted on an electronic newsgroup on the internet in early 2001,[162] many years before their existence was officially announced to the general scholarly community. It is said that history is bound to repeat itself.

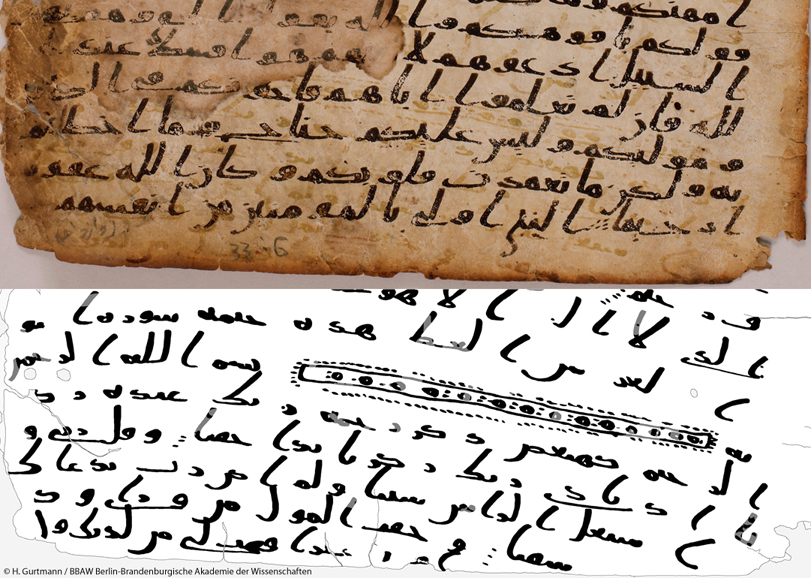

After being invited to Yemen to restore a large number of badly damaged early Qur’anic manuscripts discovered in the old mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, in the process of conserving them, the German team began to systematically photograph them after being inspired to do so based on an observation made by Christoph Luxenberg at a lecture given by him in 1996.[163]

Without the express permission of their Yemeni hosts, the original director of the project Gerd-R. Puin attempted to leave the country with some 35,000 images and was subsequently prevented from doing so. Only once Puin succeeded in enlisting the help of the German Government via local German diplomats was the initial resolve of the Yemenis broken, who finally granted the microfilms passage out of the country.[164]

Unlike the previously described endeavour, the Yemenis possess the master set of 44 microfilms of the Ṣanʿāʾ manuscripts, including three additional copies, and own the copyright. A fourth copy is in the personal possession of Hans Casper Graf Von Bothmer.[165]

In spite of the fact a significant quantity are sold at auction,[166] it goes without saying none of the Qur’anic manuscripts listed above, that are now located in the West, are indigenous there. One will also notice some surprising omissions.

The most obvious is modern day Saudi Arabia. It would seem inconceivable the birth place of Islam and the Qur’an would not have any early Qur’an manuscripts, despite the fact many of its manuscripts would have moved to different parts of the Muslim community as the spheres of power and influence became progressively spread out.

This surprising omission can probably be attributed to a lack of searching and cataloguing, an endemic problem in the vast majority of Muslim countries.

What are the major manuscript discoveries of the Qur’an in modern times? If one limits the scope of the term ‘discovery’ to those collections containing a sizeable amount of early material that were previously ‘unknown’ (at least in a modern sense), excluding unstudied or understudied collections, then one can identify two landmark events.

In 1893 a fire broke out at the Great Mosque of Damascus (Umayyad Mosque) during which a forgotten storeroom containing a huge quantity of used Qur’anic manuscripts was discovered.

Those manuscripts which escaped destruction were sent to Istanbul by the Ottoman authorities where they were ‘forgotten’ about once again, until two French scholars ‘re-discovered’ them in 1963 at the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art, Istanbul, Turkey, simply labelled as “Papers from Damascus”.[167]

They initially estimated the find to number in the thousands, perhaps dozens of thousands. However, Déroche who studied the collection in depth estimated there were about 210,000 folios, being mostly Qur’ans.[168]

At least in terms of size, this is perhaps this most significant ‘discovery’ of Qur’anic manuscripts ever made or ever likely to be made. Just two years later in 1965, heavy rains damaged the roof construction of the Western Library in the Great Mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen – a mosque established by a companion of Prophet Muhammad.

Qādī Hussain bin Ahmed al-Sayaghy, the then Director of Administration at the Yemen National Museum, instructed an examination of the area concerned be carried out to assess the extent of the damage.

During this time a forgotten storeroom with no access door and a single window was discovered to contain a substantial cache of used Arabic manuscripts, almost all being ancient manuscripts of the Qur’an spanning the first few Islamic centuries. Before repairs to the storeroom were complete, five or more sacks of Qur’anic manuscripts were removed and deposited in the Awqāf Library.

Over time the curator of the library sold off the contents of the sacks unlawfully with some of the manuscripts ending up in Western libraries. In 1972 in order to consolidate the north-west corner of the external wall to the mosque, it was necessary to remove part of the roof to allow progress to be made in the restoration and renovation works. As the storeroom was also located in this area the remaining manuscripts were permanently removed consisting of some twenty sacks and placed in the National Museum.[169]

After the work had been completed, the assessment concluded there were almost 1,000 unique copies of the Qur’an comprising approximately 15,000 parchment fragments, with less than 1% of the find belonging to non-Qur’anic material.[170] Regrettably, despite the large period of time that has elapsed since these finds, only a fraction of their manuscripts has ever been published.[171]

4. The Value Of The Qur’ānic Manuscripts From 1st Century Hijra – An Assessment

The assessment of the value of the Qur’anic manuscripts from 1st century hijra requires tabulation and assessment of their contents, both individually and collectively. These contents can be evaluated as number of verses or the percentage of the actual text these verses represent.

As for the latter, we choose the Muṣḥaf of Madinah as a standard to evaluate the actual text – a procedure similar to Noseda’s who compared the contents of the Qur’an in the ḥijāzī manuscripts with the equivalent pages of the so-called King Fuʾād edition. But first we need to understand the ‘textual dynamics’ of the Muṣḥaf of Madinah.

TEXTUAL DYNAMICS OF THE MUṢḤAF OF MADINAH

The Muṣḥaf al-Madinah or the Muṣḥaf of Madinah, is one of the most recognized and successful printings of the Qur’an in the world. This gold-on-green hardback of this muṣḥaf has no peers with at least 135 million extant copies (c. 1996).[172] The Arabic text of the Qur’an is prepared, scrutinized, verified and printed at the King Fahd Holy Qur’an Printing Complex in Madinah.

This printing complex is a 250,000 sq. m. plant and capable of producing more than 10 million copies annually. The most circulated Muṣḥaf of Madinah is in the reading of Ḥafṣ. The popularity of this edition is such that the arrangement of the text is also emulated by editions of the Qur’an printed in Beirut and Damascus.

At the printing complex, the Qur’an in the reading of Warsh is also produced but its usage is largely confined to the North Africa. Furthermore, the centre has also prepared the editions of the readings of Dūrī and Qālūn.

The Muṣḥaf of Madinah is in the reading of Ḥafṣ, and just like any other Qur’an text it is divided into 30 parts or ajza’ (sing. juz’). On an average every juz’ occupies 20 pages (and there are 15 lines per page) except for the first and the last juz’. In the first juz’, sūrah al-Fātiḥah and the first five verses of sūrah al-Baqarah occupy a page each.

That makes the first juz’ to extend an extra page, thus making it 21 pages long. As for the last juz’, due to the presence of a lot of sūrah titles and accompanying basmala, the text extends by three pages, making it 23 pages long. Therefore, what would have been a 600 page book (i.e., 30 ajza’ x 20 pages) has now become a 604 page book.

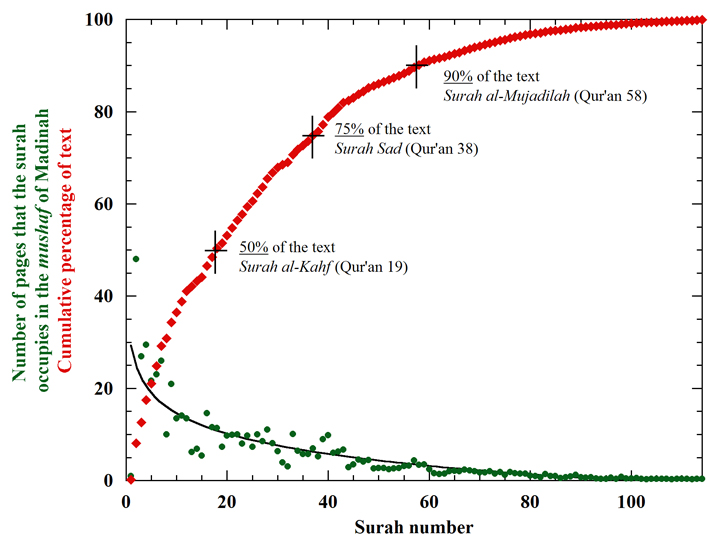

Figure 1: ‘Textual dynamics’ of the widely used Qur’an muṣḥaf printed in Madinah. It is seen that the number of pages the sūrahs occupy in the muṣḥaf decreases in an exponential fashion. However, the cumulative percentage of the text shows that almost 90% of the text of the Qur’an is present between sūrah al-al-Fātiḥah and sūrah al-Mujādilah (i.e., between Qur’an 1 and 58). The rest of the 56 sūrahs contribute just 10% of the text!

The Muṣḥaf of Madinah follows the traditional arrangement of the 114 sūrahs of the Qur’an and has a total of 6236 verses. It is seen that the number of pages a sūrah occupies in the muṣḥaf decreases in an exponential fashion (Figure 1). Another way of looking at the text is the relationship between the cumulative percentage of the text of the Qur’an and sūrahs or what we term as ‘textual dynamics’ (Figure 1).

It is seen that 50% of the text of the Qur’an is reached at sūrah al-Kahf (Qur’an 18). The text between sūrah al-Fātiḥah and sūrah al-Mujadilah (Qur’an 58) amounts to 90%. This means that the last 56 sūrahs (or 49% of the sūrahs) contribute only 10% of the text! This interesting information, though not very obvious, will be very useful when we analyze the data from the Qur’anic manuscripts.

SŪRAHS IN THE MANUSCRIPTS – WHAT AND HOW MUCH?

Table II below gives a listing of manuscripts with the sūrahs they contain, corresponding verses, total number of unique verses represented and percentage of verses contained in the sūrah. The manuscripts against a sūrah are separated by a semicolon and likewise the verses they contain in that sūrah. Highly fragmented text such as that found in P. Michaélidès No. 32 is considered only to represent the sūrahs it contains but it is not taken into account for calculation of total number of unique verses.

Those manuscripts or sūrahs whose contents or some of their contents have only been mentioned vaguely, are not included in the calculation. For instance, although it is clear DAM 20-33.1 contains every sūrah between the range of 99 up to and including the last sūrah 114, we have not included it in the table as no specific listing of their contents has been given by von Bothmer.[173]

There are two important properties required by any mathematical calculation to ensure its viability. The calculation must be (a) verifiable and, (b) repeatable. As such, all the proceeding calculations have been independently summed and reproduced so the interested reader can establish for himself whether what is being presented faithfully represents what is being claimed.

| No. | Qur’anic sūrah | Manuscripts containing the sūrah | Verses represented in manuscripts | Total unique number of verses represented in manuscripts | Total Number of Verses (Muṣḥaf of Madinah) | Percentage of verses represented in manuscripts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | al-Fātiḥah | DAM 20-33.1 DAM 01-25.1 | 1-7 (3-7) | 7 | 7 | 100 % |

| 2 | al-Baqarah | DAM 01-25.1 DAM 20-33.1 DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 AMAS Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 31 / Stanford 2007 Sotheby’s 1992, Lot 551 / David 86/2003 Arabe 328a Marcel 17 Ms. Qāf 47 DAM 01-18.9 | 1-16 39-43 140-186 125-191, 201-258 246-265, 286 265-277 277-286 275-286 269-286 269-286 251-255, 282-286 | 174 | 286 | 60.8 % |

| 3 | āl-ʿImrān | Marcel 17 AMAS Arabe 328a Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 34 DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 330g Ms. Qāf 47 DAM 01-18.9 TIEM ŞE 12827/1 | 1-200 1-154, 179-200 1-43, 84-200 34-184 36-55, 153-156, 164-175 185-200 1-14, 56-78, 100-200 1-6 198-200 | 200 | 200 | 100 % |

| 4 | al-Nisā | Arabe 328a Arabe 330g Marcel 17 Marcel 3 M. 1572b (ff. 2-6, 8-9) AMAS Bonham’s 2000, Lot 13 Christies 2008, Lot 20 Ar. Pal. Pl. 44 Ms. Or. Fol. 4313 DAM 01-29.1 Ms. Qāf 47 TIEM ŞE 12827/1 Arabe 7194 Arabe 7195 | 1-176 1-172 1-129 92-176 129-176 1-33, 56-171 33-56 171-176 54-62 137-155, 172-176 31-60, 89-119 1-137 1-2 (129-139) (119-128) | 176 | 176 | 100 % |

| 5 | al-Mā’idah | Arabe 328a AMAS Ms. Or. Fol. 4313 Ms. 67 M. 1572b (ff. 2-6, 8-9) Arabe 328e LNS 19 CAab (LNS 63 MS e) Christie’s 2008, Lot 20 Louvre Abu Dhabi Ms. 1611-MKH235 QUR-1-TSR DAM 01-29.1 Rennes Encheres 2011, Lot 151 TIEM ŞE 9052 Marcel 3 Arabe 7191 Arabe 7193 Arabe 7195 | 1-33 32-111 1-87 63-120 1-27 7-65 89-120 1-9 9-32 7-12 18-29 18-70 (18-106) 3-5 1-5 (94-107) (30-38) (1-28) | 120 | 120 | 100 % |

| 6 | al-Anʿām | Ms. 67 LNS 19 CAab (LNS 63 MS e) Arabe 328a Arabe 328e M. 1572b (ff. 2-6, 8-9) DAM 01-27.1 Sotheby’s 2010, Lot 3 DAM 01-29.1 Rennes Encheres 2011, Lot 151 Ms. Qāf 47 Marcel 3 | 1-20 1-12 20-165 39-112 74-143 49-73, 149-165 141-158 74-111 (19-41) 45-51, 53-79 25-153 | 165 | 165 | 100 % |

| 7 | al-Aʿrāf | Arabe 328a Ms. Or. 2165 AMAS Arabe 6140a DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-27.1 DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 330g Christies 2013, Lot 50 Arabe 331 | 1-206 42-206 40-206 129-179 29-206 1-11 70, 83, 134-157 127-206 169-194 162-206 | 206 | 206 | 100 % |

| 8 | al-Anfāl | Ms. Or. 2165 AMAS Arabe 330g Arabe 331 Arabe 328a Ms. Add. 1125 Marcel 18/1 DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-29.1 Ms. Qāf 47 DAM 01-18.3 DAM 01-18.9 | 1-75 1-75 1-75 1-75 1-25 10-73 25-75 1-34 11-41 10-53 2-11 73-75 | 75 | 75 | 100 % |

| 9 | Tawbah | Arabe 330g Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 18/1 Arabe 328a Arabe 6140a AMAS DAM 01-27.1 Ms. Qāf 47 DAM 01-20.4 DAM 01-18.9 Arabe 331 | 1-129 1-95 1-66 66-129 23-69 1-71, 128-129 112-115, 124-127 94-129 71-80 1-6, 127-129 1-35 | 129 | 129 | 100 % |

| 10 | Yūnus | AMAS Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328a Vaticani Arabi 1605 Arabe 328c Arabe 330g DAM 01-25.1 Ms. Qāf 47 DAM 01-18.9 | 1-109 9-109 1-78 102-109 35-109 1-31 22-51 1-7, 105-109 1-7 | 109 | 109 | 100 % |

| 11 | Hūd | Ms. Or. 2165 AMAS Vaticani Arabi 1605 KFQ60 Arabe 328c Ms. Qāf 47 DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-20.4 Arabe 7192 E16264 R | 1-123 1-123 1-13 14-35 1-110 1-42, 92-121 6-31 40-48 119-123 (48-51, 57-60) | 123 | 123 | 100 % |

| 12 | Yūsuf | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328a DAM 01-20.4 AMAS Sotheby’s 2011, Lot 1 Arabe 7192 | 1-111 84-111 65-100 1-49 30-50 (1-50) | 111 | 111 | 100 % |

| 13 | al-Rʿad | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328a | 1-43 1-43 | 43 | 43 | 100 % |

| 14 | Ibrāhīm | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328a DAM 01-29.1 Sotheby’s 2008, Lot 3 (= Ms. 699.2007) DAM 01-27.1 DAM 01-29.1 TIEM ŞE 54 Ms. Qāf 47 Arabe 331 | 1-52 1-52 43-52 19-44 32-41, 52 24-52 26-52 32-52 9-52 | 52 | 52 | 100 % |

| 15 | al-Ḥijr | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 331 Arabe 328a DAM 01-29.1 DAM 01-27.1 TR:490-2007 Arabe 330c Ms. Qāf 47 TIEM ŞE 54 | 1-99 1-99 1-87 1-20 1-16 58-99 14-99 1-9 1-2 | 99 | 99 | 100 % |

| 16 | al-Nahl | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 330c DAM 01-27.1 TR:490-2007 DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 Ms. Leiden Or. 14.545b | 1-128 1-128 73-128 1-20 86-128 1-64, 114-128 96-114 | 128 | 128 | 100 % |

| 17 | al-Isrāʾ | Ms. Or. 2165 DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-29.1 TIEM ŞE 321 Arabe 330c Marcel 13 Arabe 331 | 1-111 1-6, 40-77 35-111 93-96, 100-111 1-4, 53-96 101-111 1-59 60-111 1-4, 78-111 | 111 | 111 | 100 % |

| 18 | al-Kahf | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 13 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 19 M. 1572a (ff. 1, 7) DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 DAM 01-25.1 Arabe 331 | 1-110 1-110 1-110 30-110 17-31 22, 32 1-110 22-45 1-6 | 110 | 110 | 100 % |

| 19 | Maryam | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 13 Marcel 19 TIEM ŞE 321 DAM 01-29.1 DAM 01-27.1 M. 1572a (ff. 1, 7) M a VI 165 DAM 01-25.1 | 1-98 1-98 1-98 1-98 89-98 38-98 91-98 1-98 46, 64 | 98 | 98 | 100 % |

| 20 | Ṭāhā | Ms. Or. 2165 DAM 01-29.1 Marcel 13 DAM 01-27.1 TIEM ŞE 321 M. 1572a (ff. 1, 7) Arabe 328c M a VI 165 DAM 01-25.1 Arabe 7193 | 1-135 1-135 1-135 1-130 1-120 1-40 99-135 1-135 72, 86 (47-66) | 135 | 135 | 100 % |

| 21 | al-Anbiyā | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328c Marcel 13 DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 DAM 01-29.1 Ms. Qāf 47 TIEM ŞE 13316/1 | 1-112 1-112 1-112 16-19, 38-92, 109-112 1-112 1-50 36-45, 55-66 52-69 | 112 | 112 | 100 % |

| 22 | al-Ḥajj | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328c Marcel 13 DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 DAM 01-29.1 | 1-78 1-78 1-78 1, 15-16 1-78 36-78 | 78 | 78 | 100 % |

| 23 | al-Muʾminūn | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 18/1 Marcel 19 Arabe 328c M a VI 165 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 13 | 1-118 15-118 75-118 1-27 1-118 78-100 1-12 | 118 | 118 | 100 % |

| 24 | al-Nūr | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 18/1 Marcel 19 M a VI 165 DAM 01-25.1 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 13 | 1-64 1-64 1-64 1-64 2-25, 27-43 1-24, 40-60 49-61 | 64 | 64 | 100 % |

| 25 | al-Furqān | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 18/1 Marcel 19 DAM 01-27.1 Arabe 328f P. Cair. B. E. Inv. No. 1700 M a VI 165 Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 11, 15 Marcel 18/2 Marcel 15 TIEM ŞE 118 Arabe 331 | 1-77 1-77 1-77 10-59 77 41-51 1-77 31-60 72-77 16-77 41-58 65-77 | 77 | 77 | 100 % |

| 26 | al-Shuʿarā | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 18/1 Marcel 18/2 Marcel 15 Arabe 328f DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 Arabe 331 | 1-227 1-227 1-227 1-227 1-51 83-156, 167-189, 208-227 155-176, 198-221 1-227 1-19 | 227 | 227 | 100 % |

| 27 | al-Naml | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 18/1 Marcel 18/2 DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 Marcel 15 Marcel 16 Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 11, 15 | 1-93 1-93 1-93 25-29, 46-49 1-93 1-89 66-93 88-93 | 93 | 93 | 100 % |

| 28 | al-Qaṣaṣ | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 16 Marcel 18/2 Marcel 18/1 Is. 1615 I A Perg. 2 Arabe 328f DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 TIEM ŞE 56 Sotheby’s 1993, Lot 11, 15 | 1-88 1-88 1-88 1-53 6-22, 25-38, 42-61, 64-82, 84-88 61-80 10-32 58-86 1-88 83-88 1-16 | 88 | 88 | 100 % |

| 29 | al-ʿAnkabūt | Ms. Or. 2165 TIEM ŞE 56 Marcel 18/2 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 16 | 1-69 1-69 1-69 1-14, 18-33, 35-50, 54-69 29-40, 43-54 1-69 7-69 1-69 | 69 | 69 | 100 % |

| 30 | al-Rūm | Ms. Or. 2165 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 56 Marcel 16 Marcel 18/2 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 Marcel 18/1 M a VI 165 Marcel 11 | 1-60 1-60 1-60 1-60 1-60 1-7, 9-28, 30-47, 49-60 26-54 58-60 1-60 3-60 | 60 | 60 | 100 % |

| 31 | Luqmān | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 11 Marcel 18/2 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 56 Marcel 18/1 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 86 M a VI 165 Marcel 16 | 1-34 1-34 1-34 1-34 1-34 1-23 1-9, 13-26, 30-34 24-34 33-34 12-23 1-34 1-23 | 34 | 34 | 100 % |

| 32 | al-Sajdah | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 11 DAM 01-27.1 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 56 Is. 1615 I M a VI 165 Marcel 18/2 | 1-30 1-30 1-30 1-30 1-30 1-9, 13-30 1-30 1-16 | 30 | 30 | 100 % |

| 33 | al-Aḥzāb | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 11 DAM 01-27.1 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 56 Is. 1615 I M a VI 165 DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-29.1 | 1-73 1-73 1-37 1-55 1-59 1, 4-15, 18-32, 43 1-73 20-45 50-73 | 73 | 73 | 100 % |

| 34 | Sabʾ | Ms. Or. 2165 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 DAM 01-29.1 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 11 Marcel 13 TIEM ŞE 3591 | 1-54 1-33, 36-54 52-54 1-54 1-10 9-54 1-19 19-54 16-22 | 54 | 54 | 100 % |

| 35 | Fāṭir | Ms. Or. 2165 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 13 Is. 1615 I Arabe 328a DAM 01-27.1 M a VI 165 | 1-45 1-45 1-45 1-32, 34-44 13-41 1-18 1-45 | 45 | 45 | 100 % |

| 36 | Yāsīn | Ms. Or. 2165 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 13 Is. 1615 I M a VI 165 DAM 01-29.1 | 1-83 1-83 1-83 1-28, 31-50, 54-83 1-57 75-83 | 83 | 83 | 100 % |

| 37 | al-Ṣāffāt | Ms. Or. 2165 TIEM ŞE 321 Marcel 13 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 E. 16269 D DAM 01-29.1 | 1-182 1-182 1-182 1-45, 47-145, 149-182 38-59, 73-88, 102-172 170-182 1-27, 35-81 | 182 | 182 | 100 % |

| 38 | Ṣād | Ms. Or. 2165 Marcel 13 TIEM ŞE 321 Arabe 328a Is. 1615 I E. 16269 D DAM 01-27.1 | 1-88 1-88 1-88 66-88 1-10, 20-27, 33-66, 69-88 1-13 73-75 | 88 | 88 | 100 % |

| 39 | al-Zumar | Marcel 13 Ms. Or. 2165 Is. 1615 I Arabe 328a DAM 01-27.1 DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-29.1 | 1-75 1-47 1-23, 27-45, 47-75 1-15 6 34-67 75 | 75 | 75 | 100 % |

| 40 | Ghāfir | Marcel 13 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-29.1 Ms. Or. 2165 Christies 2011, Lot 10 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 13884 | 1-85 1-7, 10-22, 27-40, 42-59, 62-85 1-34 61-85 66-85 84-85 67-84 | 85 | 85 | 100 % |

| 41 | Fussilat | Ms. Or. 2165 TIEM ŞE 321 DAM 01-25.1 Arabe 328b Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 Christies 2011, Lot 10 Marcel 11 Marcel 13 | 1-54 1-54 2-16, 20-54 31-54 1-49, 51-54 17-27, 33-43, 47-54 1-10 10-32 1-10 | 54 | 54 | 100 % |

| 42 | al-Shūra | Ms. Or. 2165 Arabe 328b TIEM ŞE 321 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-29.1 DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-27.1 Arabe 328d | 1-53 1-53 1-53 1-12, 15-46, 48-53 45-53 1-53 1-5, 10-16, 21-29, 38-48 6-53 | 53 | 53 | 100 % |

| 43 | al-Zukhruf | Arabe 328b TIEM ŞE 321 Ms. Or. 2165 DAM 01-29.1 DAM 01-25.1 Is. 1615 I DAM 01-27.1 Arabe 328d Arabe 331 | 1-89 1-89 1-71 16-30, 77-89 1-89 1-32, 35-89 63-69, 89 1-17 81-89 | 89 | 89 | 100 % |

| 44 | al-Dukhān | Arabe 328b DAM 01-25.1 TIEM ŞE 321 DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 DAM 01-27.1 Is. 1615 I TIEM ŞE 3702 b | 1-59 1-59 1-59 1-19 1-28 1-11 1-20, 23-57, 59 28-47 | 59 | 59 | 100 % |

| 45 | al-Jāthiya | Arabe 328b Is. 1615 I DAM 01-25.1 DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 TIEM ŞE 321 | 1-37 1-37 1-29, 35-37 25-37 9-37 1-16 | 37 | 37 | 100 % |

| 46 | al-Aḥqāf | DAM 01-29.1 Is. 1615 I Arabe 331 Arabe 328b DAM 01-25.1 TIEM ŞE 321 | 1-35 1-27, 29-35 1-8, 21-35 1-8 1-3, 15-17 32-35 | 35 | 35 | 100 % |

| 47 | Muḥammad | DAM 01-29.1 Is. 1615 I Arabe 331 DAM 01-27.1 TIEM ŞE 321 | 1-38 1-4, 7-17, 20-34, 38 1-16, 36-38 15-20, 33-38 1-13, 38 | 38 | 38 | 100 % |

| 48 | al-Fataḥ | DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 Is. 1615 I A 6988 DAM 01-27.1 TIEM ŞE 321 | 1-29 1-29 1-11, 14-24 25-29 1-2 1-17 | 29 | 29 | 100 % |

| 49 | al-Ḥujurāt | DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 A 6988 | 1-18 1-18 1-7 | 18 | 18 | 100 % |

| 50 | Qāf | DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 | 1-45 1-45 | 45 | 45 | 100 % |

| 51 | al-Dhāriyāt | DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 A Perg. 213 | 1-60 1-60 3-60 | 60 | 60 | 100 % |

| 52 | al-Ṭūr | DAM 01-29.1 Arabe 331 A Perg. 213 | 1-49 1-49 1-49 | 49 | 49 | 100 % |

| 53 | al-Najm | Arabe 331 DAM 01-29.1 A Perg. 213 TIEM ŞE 321 | 1-62 1-52 1-32 52-62 | 62 | 62 | 100 % |

| 54 | al-Qamar | Arabe 331 TIEM ŞE 321 TIEM ŞE 4321 P. Michaélidès No. 32 | 41-55 1-22 39-55 (11-38, 45-55) | 39 | 55 | 70.9 % |

| 55 | al-Raḥmān | Arabe 331 P. Michaélidès No. 32 DAM 01-27.1 DAM 20-33.1 TIEM ŞE 4321 | 1-78 (1-32) 16-78 55-78 1-13 | 78 | 78 | 100 % |

| 56 | al-Wāqiʿah | Arabe 331 DAM 01-27.1 Marcel 18/1 DAM 20-33.1 | 1-96 1-69 53-96 1-20 | 96 | 96 | 100 % |

| 57 | al-Ḥadid | Arabe 331 Marcel 18/1 DAM 01-27.1 | 1-29 1-26 1-10, 16-22, 27-29 | 29 | 29 | 100 % |

| 58 | al-Mujādilah | Arabe 331 DAM 01-27.1 | 1-22 1-6, 11-22 | 22 | 22 | 100 % |

| 59 | al-Ḥashr | Arabe 331 DAM 01-27.1 | 1-24 1-10, 14-24 | 24 | 24 | 100 % |

| 60 | al-Mumtaḥinah | DAM 01-27.1 Arabe 328b Arabe 331 TIEM ŞE 87 | 1 7-13 1 7-13 | 8 | 13 | 61.5 % |

| 61 | al-Ṣaff | Arabe 328b TIEM ŞE 87 | 1-14 1-14 | 14 | 14 | 100 % |

| 62 | al-Jumuʿah | Arabe 328b TIEM ŞE 87 | 1-11 1-11 | 11 | 11 | 100 % |

| 63 | al-Munāfiqūn | Arabe 328b TIEM ŞE 87 Ms. Leiden Or. 14.545c Ms. Qāf 47 | 1-9 1-9 1-11 8-11 | 11 | 11 | 100 % |

| 64 | al-Taghābūn | Ms. Qāf 47 Ms. Leiden Or. 14.545c | 1-2, 9-16 1-4 | 14 | 18 | 77.7 % |

| 65 | al-Ṭalāq | Arabe 328b | 2-12 | 11 | 12 | 91.7 % |

| 66 | al-Tahrīm | Arabe 328b TIEM ŞE 3687 | 1-12 12 | 12 | 12 | 100 % |

| 67 | al-Mulk | Arabe 328b DAM 20-33.1 TIEM ŞE 3687 | 1-27 21-30 1-13 | 30 | 30 | 100 % |

| 68 | al-Qalam | A. 6959 DAM 20-33.1 | 9-24, 36-45 43-52 | 33 | 52 | 63.5 % |

| 69 | al-Ḥaqqah | DAM 20-33.1 Arabe 328b DAM 01-29.1 A 6959 | 1-50 3-52 44-52 9-24, 36-45 | 52 | 52 | 100 % |

| 70 | al-Maʿārij | Arabe 328b DAM 01-29.1 Marcel 3 | 1-44 1-44 44 | 44 | 44 | 100 % |

| 71 | Nūḥ | Arabe 328b DAM 01-29.1 Marcel 3 | 1-28 1-28 1-28 | 28 | 28 | 100 % |

| 72 | al-Jinn | Marcel 3 Arabe 328b DAM 01-29.1 | 1-28 1-2 8-28 | 28 | 28 | 100 % |

| 73 | al-Muzzammil | Marcel 3 DAM 01-29.1 | 1-20 1-20 | 20 | 20 | 100 % |

| 74 | al-Muddathir | Marcel 3 DAM 20-33.1 DAM 01-29.1 | 1-56 56 1-28 | 56 | 56 | 100 % |

| 75 | al-Qiyāmah | Marcel 3 DAM 20-33.1 | 1-40 1-26 | 40 | 40 | 100 % |

| 76 | al-Insān | Marcel 3 | 1-31 | 31 | 31 | 100 % |

| 77 | al-Mursalāt | Marcel 3 DAM 20-33.1 | 1-50 5-27 | 50 | 50 | 100 % |

| 78 | al-Nabāʾ | Marcel 3 | 1-40 | 40 | 40 | 100 % |

| 79 | al-Nāziʿāt | Marcel 3 DAM 20-33.1 | 1-46 29-34 | 46 | 46 | 100 % |

| 80 | al-ʿAbasa | Marcel 3 | 1-42 | 42 | 42 | 100 % |

| 81 | al-Takwīr | Marcel 3 | 1-29 | 29 | 29 | 100% |

| 82 | al-Infitār | Marcel 3 | 1-19 | 19 | 19 | 100 % |

| 83 | al-Mutaffifīn | Marcel 3 | 1-36 | 36 | 36 | 100 % |

| 84 | al-Inshiqāq | Marcel 3 | 1-25 | 25 | 25 | 100% |

| 85 | al-Burūj | Marcel 3 Is. 1615 II DAM 20-33.1 | 1-10 3-22 1-5 | 22 | 22 | 100 % |

| 86 | al-Tāriq | Is. 1615 II | 1-17 | 17 | 17 | 100 % |

| 87 | al-ʿAlā | Is. 1615 II | 1-19 | 19 | 19 | 100 % |

| 88 | al-Ghāshīyah | Is. 1615 II | 1-26 | 26 | 26 | 100 % |

| 89 | al-Fajr | Is. 1615 II DAM 20-33.1 | 1-30 13-30 | 30 | 30 | 100 % |

| 90 | al-Balad | Is. 1615 II DAM 20-33.1 | 1-19 1 | 19 | 20 | 95 % |

| 91 | al-Shams | Is. 1615 II | 1-15 | 15 | 15 | 100 % |

| 92 | al-Layl | Is. 1615 II | 1-21 | 21 | 21 | 100 % |

| 93 | al-Ḍuḥa | Is. 1615 II | 1-11 | 11 | 11 | 100 % |

| 94 | al-Sharḥ | Is. 1615 II | 1-8 | 8 | 8 | 100 % |

| 95 | al-Ṭīn | Is. 1615 II | 1-8 | 8 | 8 | 100 % |

| 96 | al-ʿAlaq | Is. 1615 II | 1-19 | 19 | 19 | 100 % |

| 97 | al-Qadr | Is. 1615 II A 6990 | 1-3 (3-5) | 3 | 5 | 60 % |

| 98 | al-Bayyinah | Is. 1615 II A 6990 | 1-8 (1-4) | 8 | 8 | 100 % |

| 99 | al-Zalzalah | Is. 1615 II DAM 20-33.1 A 6990 | 1-8 2-8 (6-8) | 8 | 8 | 100 % |

| 100 | al-ʿAdiyāt | Is. 1615 II DAM 20-33.1 A 6990 | 1-11 1-8 (1-4) | 11 | 11 | 100 % |

| 101 | al-Qāriʿah | Is. 1615 II | 1-11 | 11 | 11 | 100 % |

| 102 | al-Takāthur | Is. 1615 II | 1-8 | 8 | 8 | 100 % |

| 103 | al-ʿAsr | Is. 1615 II | 1-3 | 3 | 3 | 100 % |

| 104 | al-Humazah | Is. 1615 II | 1-9 | 9 | 9 | 100 % |

| 105 | al-Fīl | Is. 1615 II | 1-5 | 5 | 5 | 100 % |

| 106 | al-Quraysh | Is. 1615 II | 1-4 | 4 | 4 | 100 % |

| 107 | al-Māʿun | Is. 1615 II | 1-7 | 7 | 7 | 100 % |

| 108 | al-Kawthar | Is. 1615 II | 1-3 | 3 | 3 | 100 % |

| 109 | al-Kafirūn | Is. 1615 II | 1-6 | 6 | 6 | 100 % |

| 110 | al-Naṣr | Is. 1615 II DAM 20-33.1 | 1 2-3 | 2 | 3 | 100 % |

| 111 | al-Masad | 5 | ||||

| 112 | al-Ikhlās | 4 | ||||

| 113 | al-Falaq | 5 | ||||

| 114 | al-Nās | DAM 20-33.1 | 3-6 | 4 | 6 | 67 % |

| Total | – | – | 6059 | 6236 | – |

Table II: Listing of sūrahs and the manuscripts which contain them. Highly fragmented texts are represented inside brackets. These are considered only to represent the sūrahs they contain but not taken into account for calculation of the total number of unique verses.

Figure 2: The percentage of the sūrah represented in the 1st century AH Qur’anic manuscripts. This graph is plotted using the information presented in Table II. Highly fragmented texts are not considered for calculating the percentages.

Based on the manuscripts and folios that have been published, the following sūrahs are represented: 1-110 and 114, meaning the sūrahs 111-113 are unrepresented in these manuscripts (Table II and Figure 2). This gives a total of 111 out of 114 sūrahs present. A total of 330 times we observe a continuous changeover from one sūrah to another in thirty three of the fifty manuscripts. In each and every one of these 330 changeovers, the sequence of sūrahs is identical to the modern printed text.

Despite being based on an incomplete data set, this is a significant observation. Not including the section of the manuscript located at al-Maktaba al-Sharqiyya, the scriptio inferior text of Codex Ṣanʿāʾ I has twelve sūrah changeovers. They are sūrah 11, 8, 9 and 19, sūrah 12 to 18, sūrah 15 to 25, sūrah 20 to 21, sūrah 34 to 13, sūrah 39 to 40, sūrah ?? to 24 and sūrah 63, 62, 89 and 90.[174]

In its original state it would of course had many more. Despite the fact a few times there is a standard sūrah changeover, considering their placement as it would have been originally, all of them can be considered non-standard. Sadeghi and Goudarzi observed these changeovers somewhat resembled the ordering of the codex of Ubayy b. Kaʿb, though the sampling size was not large enough.[175]

In any case, Sadeghi has shown that the scriptio inferior text cannot be identified with the codices known to us in the literary sources but instead it represents an independent codex, text type and textual tradition.[176] One could also add that such an explanation for the differences in sūrah orders (i.e., Companion codices) though feasible, is not the only one. There exist numerous partially written copies of the Qur’an dating well into medieval times that contain a variety of sūrah orders.[177]

This phenomenon, however, cannot be attributed to the alleged sequence of sūrahs supposedly found in codices attributed to various companions. Simple logic dictates that if a person or patron wished to copy or have copied a few or even many sūrahs for personal or public edification, he or they were not limited to copying sūrahs adjoining each other only. Thus one must carefully consider to what extent the manuscript in question was originally a full or partial copy.

Kohlberg and Amir-Moezzi state that the Qur’anic manuscripts found in the great mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ contain “significant variants in relation to the official version of the Qur’an”.[178] Of the 926 unique manuscripts of the Qur’an found in the great mosque of Ṣanʿāʾ, 22% present a sequence of sūrahs “completely different” from what is known today.[179] Kohlberg and Amir-Moezzi further go on to claim that it is striking that the sequence of sūrahs found in these manuscripts (i.e., 22% of 926) accord with the codices attributed to Ibn Masʿūd and Ubayy b. Kaʿb, both of which were held in high esteem by the ‘Alids (i.e., Shi’ites).[180]

These unsubstantiated claims do not square with the evidence presented above and are actually the product of a misreading. Von Bothmer said of the approximately 22% of the 926 Qur’anic manuscripts found in Ṣanʿāʾ, 208 manuscripts in total, contain a varying number of lines per page.[181] Von Bothmer’s statement has nothing to do with sūrah order and as such the explanations and conclusions drawn by Kohlberg and Amir-Moezzi from their misreading of von Bothmer’s statements are unconvincing and quite simply inaccurate.[182]

| No. | Qur’anic sūrah | Number of pages the sūrah occupies in the muṣḥaf of Madinah | Percentage of the sūrah in the Qur’an | Cumulative percentage | Percentage of the sūrah in the Qur’anic manuscripts (derived from equivalent number of pages in the muṣḥaf of Madinah) | Cumulative percentage of the Qur’an in manuscripts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | al-Fātiḥah | 1.0 | 0.16 % | 0.16 % | 0.16 % | 0.16 % |

| 2 | al-Baqarah | 48.0 | 7.95 % | 8.11 % | 5.04 % | 5.20 % |

| 3 | āl-ʿImrān | 26.93 | 4.46 % | 12.57 % | 4.46 % | 9.66 % |

| 4 | al-Nisā | 29.40 | 4.87 % | 17.44 % | 4.87 % | 14.53 % |

| 5 | al-Mā’idah | 21.67 | 3.60 % | 21.04 % | 3.60 % | 18.13 % |

| 6 | al-Anʿām | 23.0 | 3.81 % | 24.85 % | 3.81 % | 21.94 % |

| 7 | al-Aʿrāf | 26.0 | 4.30 % | 29.15 % | 4.30 % | 26.24 % |

| 8 | al-Anfāl | 10.0 | 1.66 % | 30.81 % | 1.66 % | 27.90 % |

| 9 | Tawbah | 20.93 | 3.47 % | 34.28 % | 3.47 % | 31.37 % |

| 10 | Yūnus | 13.47 | 2.23 % | 36.51 % | 2.23 % | 33.60 % |

| 11 | Hūd | 14.07 | 2.33 % | 38.84 % | 2.33 % | 35.93 % |

| 12 | Yūsuf | 13.47 | 2.23 % | 41.07 % | 2.23 % | 38.16 % |

| 13 | al-Rʿad | 6.13 | 1.01 % | 42.08 % | 1.01 % | 39.17 % |

| 14 | Ibrāhīm | 6.87 | 1.14 % | 43.22 % | 1.14 % | 40.31 % |

| 15 | al-Ḥijr | 5.40 | 0.89 % | 44.11 % | 0.89 % | 41.20 % |

| 16 | al-Nahl | 14.60 | 2.42 % | 46.53 % | 2.42 % | 43.62 % |

| 17 | al-Isrāʾ | 11.60 | 1.92 % | 48.45 % | 1.92 % | 45.54 % |

| 18 | al-Kahf | 11.40 | 1.89 % | 50.34 % | 1.89 % | 47.43 % |

| 19 | Maryam | 7.27 | 1.20 % | 51.54 % | 1.20 % | 48.63 % |

| 20 | Ṭāhā | 9.73 | 1.61 % | 53.15 % | 1.61 % | 50.24 % |

| 21 | al-Anbiyā | 9.93 | 1.64 % | 54.79 % | 1.64 % | 51.88 % |

| 22 | al-Ḥajj | 10.0 | 1.66 % | 56.45 % | 1.66 % | 53.54 % |

| 23 | al-Muʾminūn | 8.0 | 1.32 % | 57.77 % | 1.32 % | 54.86 % |

| 24 | al-Nūr | 9.73 | 1.61 % | 59.38 % | 1.61 % | 56.47 % |

| 25 | al-Furqān | 7.27 | 1.20 % | 60.58 % | 1.20 % | 57.67 % |

| 26 | al-Shuʿarā | 10.0 | 1.66 % | 62.24 % | 1.66 % | 59.33 % |

| 27 | al-Naml | 8.53 | 1.41 % | 63.65 % | 1.41 % | 60.74 % |

| 28 | al-Qaṣaṣ | 11.0 | 1.82 % | 65.47 % | 1.82 % | 62.56 % |

| 29 | al-ʿAnkabūt | 8.13 | 1.35 % | 66.82 % | 1.35 % | 63.91 % |

| 30 | al-Rūm | 6.40 | 1.06 % | 67.88 % | 1.06 % | 64.97 % |

| 31 | Luqmān | 3.93 | 0.65 % | 68.53 % | 0.65 % | 65.62 % |

| 32 | al-Sajdah | 3.0 | 0.5 % | 69.03 % | 0.5 % | 66.12 % |

| 33 | al-Aḥzāb | 10.07 | 1.67 % | 70.70 % | 1.67 % | 67.79 % |

| 34 | Sabʾ | 6.47 | 1.07 % | 71.77 % | 1.07 % | 68.86 % |

| 35 | Fāṭir | 5.73 | 0.95 % | 72.72 % | 0.95 % | 69.81 % |

| 36 | Yāsīn | 5.73 | 0.95 % | 73.67 % | 0.95 % | 70.76 % |

| 37 | al-Ṣāffāt | 7.0 | 1.16 % | 74.83 % | 1.16 % | 71.92 % |

| 38 | Ṣād | 5.27 | 0.87 % | 75.70 % | 0.87 % | 72.79 % |

| 39 | al-Zumar | 8.93 | 1.48 % | 77.18 % | 1.48 % | 74.27 % |

| 40 | Ghāfir | 9.87 | 1.63 % | 78.81 % | 1.63 % | 75.90 % |

| 41 | Fussilat | 6.0 | 0.99 % | 79.80 % | 0.99 % | 76.89 % |

| 42 | al-Shūra | 6.27 | 1.04 % | 80.84 % | 1.04 % | 77.93 % |

| 43 | al-Zukhruf | 6.73 | 1.11 % | 81.95 % | 1.11 % | 79.04 % |

| 44 | al-Dukhān | 2.93 | 0.49 % | 82.44 % | 0.49 % | 79.53 % |

| 45 | al-Jāthiya | 3.47 | 0.57 % | 83.01 % | 0.57 % | 80.10 % |