𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐈𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐎𝐟 𝐏𝐡𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐨𝐡 𝐃𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐓𝐢𝐦𝐞 𝐎𝐟 𝐌𝐨𝐬𝐞𝐬

Mohamad Mostafa Nassar

Twitter:@NassarMohamadMR

1. Introduction

Created for the purpose of evangelising the native peoples the colonialists were encountering as they expanded across the globe, the missions of the Christian missionaries were one of the breeding grounds for biblical archaeology in the nineteenth century[1] – and remain so until this present day. Although the earliest excavations in Egypt were not purposely developed with the intention to underwrite the biblical narrative, scholars were cognizant of the fact that ancient Egypt had been mentioned in the Old Testament, particularly in the books of Genesis and Exodus.[2]

As the mass excavation of Egypt beckoned, the colonial powers rushed forth to analyze a country full of ancient treasures spanning different religions and cultures over several millennia. In Victorian Britain much of the popular interest revolved around the ancient Egyptian connections with the Bible, especially the Exodus narrative.

It is in such a context that Amelia Edwards, an amateur Egyptologist, and Reginald Stuart Poole of the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum, founded the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Egypt Exploration Society) in 1882.[3]

Many of the early financial donors to the fund were from the clergy and those interested in finding archaeological evidence that would support the biblical narratives in respect of ancient Egypt.[4] Demonstrating the power of the biblical motivations in the establishment of the Fund, one need look no further than its first objective, “… to organise excavations in Egypt, with a view to further elucidation of the History and Arts of Ancient Egypt, and to the illustration of the Old Testament narrative, in so far as it has to do with Egypt and the Egyptians; …”[5]

One of the first publications of the Fund was an examination of the geography of the Exodus based on their first expedition to the Eastern Delta of the Nile in the spring-time of 1883.[6] Over 100 years later, it need hardly be stated the geography of the Exodus still commands the utmost attention amongst Christians worldwide, interested in underpinning the archaeological stratum of the Exodus story as found in the Old Testament.[7]

Intertwined with the geography of the Exodus is the identification of the Pharaoh(s) during the time of Moses in ancient Egypt – a subject of intense debate amongst biblical scholars. These Christian scholars can be broadly divided into two groups: one which believes that the Bible should be the sole basis of dating and the other group which uses ancient near eastern archaeology to date the Exodus. Both these groups employ certain assumptions and overlook certain details in order to reach their conclusions.

With regard to the veracity and consistency of the biblical text the choice of either position is ultimately immaterial; adopting one of the two positions results in contradicting and/or dismissing parts of the biblical story fundamental to the other position as we shall soon observe. The Christian missionaries and apologists shrewdly ignorant of the historical problems associated with the biblical story of Moses as presented in the Bible, quickly turn their attention to the Qur’an.

According to them, the Qur’an mentions that there was only one Pharaoh during the time of Moses, i.e., the Pharaoh who was present during the time of Moses was the same one who died while pursuing the Children of Israel. The Bible on the other hand mentions that Moses saw parts of the reigns of two Pharaohs (Exodus 2:23). Since the Qur’an differs from the Bible on this point, by the power of circular argument, the resultant conclusion of missionaries and apologists is that there is a historical contradiction in the Qur’an.

The relevant question which they forgot to consider during their periods of contemplation is whether the biblical story has any historical basis to prove this point. With this in mind, the identification of the Pharaoh(s) during the time of Moses according to the Bible and the Qur’an forms the subject of the foregoing discussion.

2. The Pharaohs During The Time Of Moses According To The Bible

There has been a long tradition of resolving the statements made in the Old Testament with actual archaeological discoveries.[8] One of the most vexing questions is the identification of the Pharaoh during Moses’ exodus from ancient Egypt, a subject of intense debate among biblical scholars from a wide variety of theological backgrounds. These scholars can be broadly divided into two groups: one which believes that the Bible should be the sole basis of dating and the other group which uses ancient near eastern archaeology to date the Exodus.

Both these groups employ certain assumptions and overlook certain details in order to reach their conclusions. As one will observe, proving the efficacy of the statements contained in the Old Testament is not without problems. What at first appears a seemingly harmless task has now thrust itself into the limelight once again and highlights the grave theological problems associated with editorial updating as well as numbers in the Old Testament, and the modern scholars’ ingenious attempts to harmonise them with the archaeological data.

There are two models current for dating the Exodus, the early-date model and the late-date model.[9] Both models are based on a considered amount of data both biblical and archaeological. Nevertheless, each model contains a single ‘foundational text’ that is a text on which the proponents of each respective model principally ground their entire argument and it is to this we now turn our attention.

WHEN IS A NUMBER NOT A NUMBER?

Identifying the Pharaoh of the Exodus according to the “conservative” evangelical position, the early-date model, is relatively straightforward and is primarily based on a set reading of a single verse from the Hebrew Masoretic text being the book of I Kings 6:1,

In the four hundred eightieth year after the Israelites came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the LORD.[10]

It is generally agreed that Solomon ruled c. 970 BCE due to synchronisms with Egyptian and Assyrian historical records.[11] Therefore, according to the “conservative” evangelical position, one simply adds 480 to 966/7 BCE (fourth year of Solomon’s reign) to arrive at the figure 1446/7 BCE.[12] All archaeological evidence is strictly interpreted in light of this date, i.e., one arrives at the date before one adduces supporting archaeological evidence. The Pharaoh of the Exodus according to the ancient Egyptian chronological data is thus Tuthmosis III (sometimes also written as Thutmose III) who reigned in the period 1479-1425 BCE [Figure 3(a)].

This simplistic solution, appealing though it may be, overlooks a large number of problems that span a wide range of disciplines from textual criticism to archaeology, even contradicting certain verses contained within the Old Testament itself. Firstly, although 1446/7 BCE has been claimed as “the biblical” date,[13] it is worth pointing out that I Kings 6:1 reports that the Exodus happened 480 years ago in Solomon’s fourth year

but it does not provide an actual date for Solomon’s reign from which one can reckon back in history in order to establish the date of the Exodus. Thus the Bible alone does not provide a date for the event of the Exodus. Secondly, let us now look at the same verse again according to the Greek Septuagint III Reigns 6:1,

And it happened, in the four hundred fortieth year of the departure of the sons of Israel from Egypt, in the fourth year in the second month, when King Salomon reigned over Israel, that the king commanded, and they took great, costly stones for the foundation of the house, and unhewn stones, and the sons of Salomon and the sons of Chiram hewed and laid them. In the fourth year he laid the foundation of the house of the Lord in the month Niso, the second month; in the eleventh year in the month Baal (this is the eighth month) the house was finished in all its plan and in all its arrangement.[14]

Does one follow the length of time provided by the Hebrew Masoretic text, 480 years, or the Greek Septuagint, 440 years? What are the textual reasons for preferring one text over the other? Which reading is the inspired, infallible and inerrant “Word of God”? Thirdly, irrespective if one follows either of these numbers, none of them matches the number tallied when one adopts a straightforward literal reading of individual judge reigns and other periods of time given in the Old Testament from I Kings 6 back to the book of Exodus. Fensham neatly summarises,

The period of the judges extends from the death of Joshua to the death of Samson or the beginning of the activities of Samuel. The total of all the dates given in Judges is 410 years. But 1 K. 6:1 states that the temple of Solomon was constructed in his fourth year, 480 years after the Exodus. If we take 410 years and add the 40 years spent in the desert, then the years of Joshua, Eli, Samuel, Saul, and David, then add Solomon’s years, a figure of approximately 599 years emerges, which is 119 years in excess of the 480 years given in Kings.[15]

Similar calculation by Hoffmeier of reigns derived from tallying the years in retrograde order from I Kings 6 back to the book of Exodus gave 633 years.[16] This number was achieved by assuming a minimal number where the Bible does not specify any number for a reign or judgeship. This discrepancy between counting the years in the above fashion and I Kings 6:1 has led to a number of ingenious solutions of overlapping reigns being read dogmatically into the text, which, ultimately, bases its authority on the creative interpretation of its theorizer.[17]

By doing this, one abandons a straightforward and literal reading of the Judges through Exodus narratives. In essence, we have three dates for the Exodus, i.e., from the Hebrew Masoretic text, 480 years, the Greek Septuagint, 440 years, and c. 600 years, the period derived from tallying the years backwards from I Kings 6 to the book of Exodus. These chronologies by themselves do not give an absolute date for the Exodus because the biblical data does not disclose when Solomon reigned.

These dates, when combined with c. 966/7 BCE, the fourth year of Solomon’s reign (as obtained from synchronisms with Egyptian and Assyrian historical records discussed earlier), would give the date of the Exodus as 1446/7 BCE, 1406/7 BCE and c. 1566/7 BCE, respectively. The rulers of ancient Egyptian for these dates would be Tuthmosis III (1479-1425 BCE), Amenhotep II (1425-1400 BCE), both from the New Kingdom Period, and Apophis (c. 1575-1540 BCE), a Hyksos ruler from the Second Intermediate Period, respectively.[18] The Christian missionaries’ tacit preference however is Amenhotep II.

If the numbers reported in the Hebrew Bible do not add up or cannot be harmonised in a fashion suitable for the context, then the various theories of biblical inspiration, infallibility and inerrancy are necessarily rendered void and the divine authorship of the Old Testament overstated. Additionally, one should note the theological convictions

and presuppositions of those proponents of the early-date model mean they dogmatically adhere to the Masoretic text reporting of numbers and are unable to provide a reasonable explanation of their preference for the numbers reported there as opposed to the Septuagint or Dead Sea Scrolls.

The following two representative examples will serve to illustrate the fact that such an axiomatic standard cannot be adopted without difficulty. In 1 Samuel 17:4, is Goliath six cubits and a span tall (c. 9′ 9″), or four cubits and a span tall (c. 6′ 9″)? The Septuagint and the oldest extant Hebrew witness Dead Sea Scroll 4QSama, which predates the oldest Masoretic Hebrew manuscript by around 1,000 years, agree with each other against the Masoretic Text.[19]

Remaining in the book of 1 Samuel, how many vessels are reported in verse 2:14/16? Given the choice of two vessels as per Dead Sea Scroll 4QSama, three vessels as per the Septuagint and four vessels as per the Masoretic text, Parry opts for one vessel![20] Such examples could easily be multiplied manifold.

WHEN IS A PLACE NAME NOT A PLACE NAME?

The proof text of those scholars adopting the late-date model is based on a set reading of the book of Exodus 1:11,

Therefore they set taskmasters over them to oppress them with forced labor. The built supply cities, Pithom and Rameses, for Pharaoh.[21]

Ramesses II was known to have constructed the city of Pi-Ramesses (or Pr-Ramesses, lit. “house or dwelling of Ramesses”) and it became the capital of his kingdom. By studying the usage of the name Pi-Ramesses in its egyptological context, scholars of ancient near eastern archaeology quickly identified the residence named in Exodus 1:11 must be referring to the same city. Attempts have been made by those scholars who support the early-date model to “prove” that the name Ramesses existed before the advent of Ramesses.[22]

However, of those cities that used the name Ramesses, none of them predate the reign of Ramesses II. This particular issue was studied in-depth by prominent Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner over 90 years ago.[23] He concluded that:

To sum up: whether or no the Bible narrative be strict history, there is not the least reason for assuming that any other city of Ramesses existed in the Delta besides those elicited from the Egyptian monuments. In other words, the Biblical Raamses-Rameses is identical with the Residence-city of Pi-Ramesses near Pelusium.[24]

The Pentateuchal occurrences of Ramesses omits the initial element Pr-/Pi-. This should not seen as a reason for distinguishing the biblical references from the Ramesside residence of the northeast Delta as the writing ‘Ramesses’ is attested in Egyptian records and was a well-known abbreviation for this city.[25] Consequently, with this data in hand, proponents of the late-date model hold the Pharaoh of the Exodus to be Ramesses II who reigned from 1279-1213 BCE. This dating of the Exodus enjoys popularity among scholars.[26]

Appreciating their position is confounded by the numerical data given in the Masoretic and Septuagint text of 1 Kings 6:1, the proponents of the late-date model deal with this contradiction by resorting to a numerical substitution theory as follows. First, they start with the number 480 as reported in the Masoretic text of the Old Testament. Second, 40 years is judged as being the ‘ideal’ generation, giving 480 / 40 = 12 generations in total. However, the value 40 is substituted for its actual real mathematical value of 25, as this is “closer” to the “actual” length of a generation. Third, the mathematical calculation continues to its conclusion giving 12 x 25 = 300.

One is thus treated to a master class of number transformation whereby the number 480 really represents the actual mathematical numerical value 300. Subsequently, this actual mathematical numerical value 300 is added to the fourth year of Solomon’s reign 966/7 to give the date 1266/7 BCE or 1241/2 BCE if one follows the Septuagint – a date in consonance with the data provided in Exodus 1:11. The value 25 has been chosen due to its popularity. One will sometimes find 22, 20 and other numbers of the interpreters’ choosing.[27]

The proponents of the early-date model argue that should the numerical substitution theory be carried forward to its logical conclusion, other numbers contained in the Old Testament become meaningless and open to interpretation according to the whim and fancy of the interpreter. Therefore, dogmatically adopting the early-date model becomes the only meaningful solution for them.

Realising the problem such an interpretation of Exodus 1:11 poses in that it directly contradicts the data provided elsewhere in the Old Testament regarding number of years elapsed since the Israelites came out of Egypt, the proponents of the previously discussed early-date model, in order to escape the charge of historical contradiction or anachronism, affirm that “editorial updating” has occurred.[28]

According to them, this means that the name of the store/supply city built by the Pharaoh called Rameses in Exodus 1:11 was originally named something else. That is, the theoretical original reading, which is presently unknowable and cannot be ascertained from the extant biblical manuscripts, has in fact been updated by an unknown, unnamed editor(s) centuries after Moses allegedly composed his text.

Other well-known historical anachronisms in the Bible due to “editorial updating”, to name but a few, are mention of the Pharaohs when the rulers of ancient Egypt were not even called Pharaohs, appearance of the name Potiphar in the time of Joseph when the name Potiphar itself post-dates both Joseph and Moses, and the anachronistic mention of the coin daric in the time of David. Thus the issue of “editorial updating” leaves Moses seeing parts of the reigns of two Pharaohs as mentioned in the Bible (Exodus 2:23) in a position where its historicity is as dubious as the numbers and the names mentioned in the story.

How can proponents of the early-date model accept that books of the Old Testament have been edited after their supposed completion by their inspired authors? The answer is quite simple: “inspired textual updating”.[29] Scholars of all theological persuasions have long since accepted that books of the Old Testament have been updated and changed long after their supposed completion by their inspired authors.

Needless to say, the multitude of creeds arising from the Protestant Reformation, some of which the Christian missionaries and apologists affirm as part of their Church constitutions and memberships, contain no hint of “inspired textual updating” and implicitly teach otherwise.[30]

Let us consider the following statements of three creeds popular amongst the English speaking evangelical protestant Churches of which many of the modern day Christian missionaries and apologists are an integral functioning part. Apart from minor spelling and punctuation differences and the (unintentional?) omission of a single word in the Savoy Declaration, article VIII of the Westminster Confession of Faith, the Savoy Declaration and the Baptist Confession of Faith states,

The Old Testament in Hebrew (which was the Native Language of the people of God of old,) and the New Testament in Greek, (which at the time of the writing of it was most generally known to the Nations) being immediately inspired by God, and by his singular care and providence kept pure in all Ages, are therefore authenticall; so as, in all Controversies of Religion, the Church is finally to Appeale unto them.[31]

All three confessions speak about the eternal purity and inspiration of the biblical text and the absence of any errors therein as a function of God’s singular care and providence. For the purposes of our discussion, one will also note the final appeal in any religious controversy should be to the Hebrew text of the Old Testament.

With a head start of a few hundred years of biblical criticism, modern declarations such as the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy are very carefully worded so as to avoid present and potential problems in light of current and future biblical research. One need look no further than the penultimate sentence of the denial clause (i.e., the ‘get out’ clause) of the final article XIX,

We deny that such confession [of the full authority, infallibility, and inerrancy of Scripture] is necessary for salvation. However, we further deny that inerrancy can be rejected without grave consequences, both to the individual and to the church.[32]

The framers of the confession, the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy (ICBI) published their official commentary on the statement in 1980 after it was decided in 1979 by a draft committee of the ICBI that the statement itself should not be modified. This commentary is especially useful in that its stated intention is to clarify the precise position being proclaimed in the nineteen articles of affirmation and denial. With regard to the denial statement of article XIX, the author of the commentary and the first draft of the nineteen articles R. C. Sproul says,

The denial in Article XIX is very important. The framers of the confession are saying unambiguously that confession of belief in the inerrancy of Scripture is not an essential of the Christian faith necessary for salvation… We do not regard acceptance of inerrancy to be a test for salvation.[33]

When one reflects on the statement one can better understand why the Christian missionaries and apologists are comfortable in their own self-proclaimed faith whilst acknowledging there are grave problems and insoluble errors in the Bible. Let us now move from the last article to the first article. Here the ICBI purposefully omitted reference to the number of books comprising the canon of the Bible due to established historical variances on the composition of the canon throughout Christendom.[34]

What remains is a cleverly developed pragmatic solution whereby one may believe in an undelineated Bible that contains errors whilst maintaining one’s right to “salvation” – a paradoxical compromise, one though that is heartily accepted. As ‘inerrancy’ has been dubbed the “shibboleth” of the Protestant evangelical community, it is recognised there are a multitude of different explanations of ‘inerrancy’, its relevance and scope. The ICBI statement enjoys popularity and wide acceptance among prominent evangelical leaders whom the missionaries and apologists regularly reference as spiritual and academic authorities.

As has been observed, “editorial updating” and “inspired textual updating” function as two opportune devices to explicate the Old Testament from historical, geographical and linguistic errors, and becomes an indispensable tool for those proponents of the early-date model. Integrated within a flexible creedal system of beliefs, this inherently contradictory position is mitigated by the prospect of “salvation”.

THE ‘NEW CHRONOLOGY’ AND THE DATE OF EXODUS

One of the hallmarks of the Christian apologists’ claim about the “historical” dating of the event of Exodus is inconsistency. Earlier, we have seen how the missionaries tacitly subscribe to the early-date model, which, according to them, gives Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. This conclusion is arrived at by using the accepted chronology of the rulers of ancient Egypt. At the same time the missionaries also subscribe to the “new chronology” of ancient Egypt as put forth by David Rohl.[35]

The reason for their acceptance of the “new chronology” is quite simple – giving historical credence to the events mentioned in the Bible. Rohl attempted to produce a revision of the accepted chronology of ancient Egypt that would make possible the synchronization of events found in Egyptian texts with those in the Bible. In doing so, he makes a drastic revision of the accepted ancient Egyptian chronology.

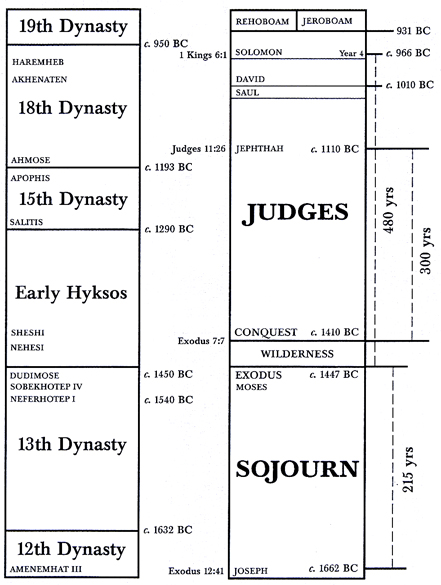

Figure 1: The “new chronology” (left column) as proposed by David Rohl and the biblical chronology (right column).[36]

Rohl uncritically accepts the chronology of the Exodus mentioned in the Hebrew Bible even though there exists serious contradictions. Therefore, not surprisingly, according to him, the Exodus happened c. 1447 BCE [Figure 1]. In effect, Rohl’s attempt may be considered as a subset to the early-date model. With his “new chronology” the ruler during the event of the Exodus was not Amenhotep II as tacitly subscribed to by the missionaries, but Dudimose from the 13th Dynasty of the Second Intermediate Period.

The precise dates of the reign of Dudimose in the accepted chronology of ancient Egypt are uncertain.[37] However, according to Rohl’s “new chronology”, Dudimose lived around c. 1450 BCE. Even more startling is the case of the widely-accepted identification of “Shishaq (or ‘Shishak’), king of Egypt” (I Kings 14:25, II Chronicles 12:2-9) with the Egyptian ruler Shoshenq I of the 22nd Dynasty in the Third Intermediate Period.

Rohl argues instead that Shishaq should be identified with Ramesses II,[38] which would move the date of Ramesses II’s reign forward by almost 300 years!

WHAT ABOUT THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE?

As previously mentioned, the archaeological evidence adduced by both groups is preceded by certain texts in the Old Testament. Neither group can function in a vacuum and must adduce the biblical evidence first which directs one to the relevant time period from which one can begin to assess the archaeological evidence. This is not something unusual and is the methodology utilised in this article for identifying the Pharaoh according to the Qur’anic data.

For an in-depth discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of the archaeological assessments made by both groups – in particular by those who still believe the Old Testament to be the inspired, infallible and inerrant word of God – as well as those topics covered above, one can consult the following recent flurry of discussion.[39]

In short, whether one ascribes to the early or late-date model, certain assumptions are employed and certain details are overlooked in order to arrive at the dating. In either case the doctrines of biblical inspiration, infallibility and inerrancy become confusing and ineffectual as numbers mean other different numbers and place names mean other different place names.

Although certain assumptions must be formed in absence of information supplied, interpreting the Qur’an does not require one to depend upon “editorial updating”, “inspired textual updating”, assigning different numerical values to mysterious numbers or deciding between which type of manuscripts and translations to rely upon to calculate those numbers.

Notwithstanding the existence of dubious data in the Old Testament, the Christian missionaries superciliously claimed that the Pharaoh depicted in the Qur’an was “A Pharaoh Who Forgot to Die in Time“. The missionaries, however, did not realise that the law of unintended consequences would result in their own perceived Schadenfreude encompassing them.

As it turns out, the contradictory data in the Hebrew Bible makes their preferred dating of the Exodus c. 1445 BCE intrinsically defective. Using the missionaries own language, one may characterise the Pharaoh of the Bible as not only “a Pharaoh who failed to appear on time” but also “a Pharaoh who forgot to appear at the right place”.

3. The Qur’an And The Pharaoh During The Time Of Moses

Like the Bible, the Qur’an does not mention the name of the Pharaoh during the time of Moses. However, it does provide sufficient clues to work out which Pharaoh it could be. In the sub-sections below, we will analyse various clues offered by the Qur’an to identify the ruler of Egypt. At the outset, we would like to say that our approach involves starting from a broader perspective, ultimately narrowing down the name of the ruler.

After that we will use the supporting evidence from the Qur’an itself to strengthen our case. It will be seen that the evidence from the Qur’an hardly requires any support from the Bible to interpret the data. In fact, much of the Qur’anic information can be interpreted from the egyptological data to arrive at a firm conclusion.

THE SETTING OF THE STORY: PHARAOH – THE RULER OF EGYPT

The kings of ancient Egypt during the time of Abraham [Genesis 12:10-20], Joseph [Genesis 41] and Moses [e.g., Exodus 2:15] are constantly addressed with the title “Pharaoh” in the Bible. The Qur’an, however, differs from the Bible: the sovereign of Egypt who was a contemporary of Joseph is named “King” (Arabic, malik); whereas the Bible has named him “Pharaoh”. As for the king who ruled during the time of Moses, the Qur’an repeatedly calls him “Pharaoh” (Arabic, firʿawn). What do modern linguistic studies and Egyptology reveal about the word “Pharaoh” and its use in ancient Egypt? The famous British Egyptologist Sir Alan Gardiner discusses the term “Pharaoh” and cites the earliest example of its application to the king, during the reign of Amenophis IV (c. 1353 – 1336 BCE) as recorded in the Kahun Papyrus. Regarding the term Pharaoh, Gardiner says:

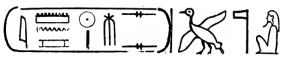

Figure 2: Sir Alan Gardiner’s discussion on the word “Pharaoh”.[40]

Gardiner also cites two possible earlier examples under Tuthmosis III (1479 – 1425 BCE) and Tuthmosis IV (1400 – 1390 BCE) (as mentioned in his footnote 10 above), while Hayes has published an ostracon from the joint reign of Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) and Tuthmosis III that twice refers to the latter simply as “Pharaoh”. Therefore, the setting of the Qur’anic story of Moses is from the time when rulers of ancient Egypt were addressed as Pharaohs, i.e., from the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period (c. 1539 – 1077 BCE) onwards until the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1076 – 746 BCE).

After the Third Intermediate Period, Egypt was ruled by weak 25th and 26th Dynasties and later by the Persians and then the Romans. These periods will not be taken into consideration for our study. So, we have narrowed almost c. 3000 years of ancient Egyptian history to a specific timescale, i.e., New Kingdom Period (c. 1539 – 1077 BCE) and the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1076 – 746 BCE) which is c. 790 years, for the setting of the Qur’anic story of Moses.

Before we go any further, a valid question to ask is how can we trust the chronology of the New Kingdom Period (c. 1539 – 1077 BCE) of ancient Egypt mentioned here? Recently, Ramsey et al. presented a comprehensive and sophisticated radiocarbon dating study on the chronology of ancient Egypt, involving 211 samples.[41]

The short-lived plant samples for 14C dating were selected from individual funerary contexts in various museum collections. Each sample could be associated with the reign of a particular ruler or with a specific section of the historical chronology. More specifically, the New Kingdom dating, based on 128 14C dates, had an average calendrical precision of 24 years.

Modelling of the date with 95% confidence suggests the beginning of the New Kingdom Period with the 18th Dynasty between 1570 BCE and 1540 BCE.[42] Giving and taking a few years, the New Kingdom chronology, suggested by egyptologists, is now validated scientifically using 14C dating.

THE PHARAOH WHO REIGNED LONG

Now that we have identified the specific timescale for the story of Moses, let us know look into the next and perhaps the most important of all clues. Unlike the Bible, the Qur’an speaks about only one Pharaoh who ruled Egypt before the birth of Moses until the Exodus and his (i.e., Pharaoh’s) death. The evidence for this comes from the Qur’an 28:7-9 and Qur’an 26:18-22.

So We sent this inspiration to the mother of Moses: “Suckle (thy child), but when thou hast fears about him, cast him into the river, but fear not nor grieve: for We shall restore him to thee, and We shall make him one of Our messengers.” Then the people of Pharaoh picked him up (from the river): (It was intended) that (Moses) should be to them an adversary and a cause of sorrow: for Pharaoh and Haman and (all) their hosts were men of sin. The wife of Pharaoh said: “(Here is) joy of the eye, for me and for thee: slay him not. It may be that he will be use to us, or we may adopt him as a son.” And they perceived not (what they were doing)! [Qur’an 28:7-9]

Here God is narrating the event after the birth of Moses and how he was cast in the river only to be picked up by people of the Pharaoh. Part of the dialogue between Moses after his return from Midian and Pharaoh, as cited in the Qur’an 26:18-22, makes it perfectly clear that this Pharaoh is the same Pharaoh who took custody of Moses in his infancy.

(Pharaoh) said: “Did we not cherish thee as a child among us, and didst thou not stay in our midst many years of thy life? “And thou didst a deed of thine which (thou knowest) thou didst, and thou art an ungrateful (wretch)!” Moses said: “I did it then, when I was in error. “So I fled from you (all) when I feared you; but my Lord has (since) invested me with judgment (and wisdom) and appointed me as one of the messengers. “And this is the favour with which thou dost reproach me,- that thou hast enslaved the Children of Israel!” [Qur’an 26:18-22]

Here Pharaoh reminds Moses of the time that he spent as a child in his household and the event when he killed a man [Qur’an 28:33] that led to his flight to Midian. The answer of Moses to Pharaoh’s argument is a clear confirmation that this Pharaoh is the same one in whose palace he was brought up. Furthermore, Moses rejected Pharaoh’s claim that he had done him a favour by letting him live in his household.

He reminded Pharaoh that the reason why he ended up in Pharaoh’s household was because the latter had enslaved the Children of Israel, which included the prohibition of the Children of Israel leaving Egypt and killing of their new born males. In essence, the same Pharaoh who enslaved the Children of Israel was in power when Moses went back to Egypt.

Keeping in mind that Moses was born when Pharaoh was already in power and that the latter died in his pursuit of Moses and the Children of Israel, the length of Pharaoh’s reign can be estimated by adding together the following:

- The number of years that Pharaoh reigned before Moses was born;

- The age of Moses when he left for Midian;

- The number of years he stayed in Midian; and

- The length of Moses second sojourn in Egypt after returning from Midian.

Firstly, the Qur’an does not state in which year of rule of Pharaoh that Moses was born. This means that we can only work out the minimum length of the reign of the monarch. Secondly, the age of Moses when he left for Midian can be drawn from the commentaries of the Qur’an 28:14.

When he reached full age [balagha ashuddah], and was firmly established (in life) [istawā], We bestowed on him wisdom and knowledge: for thus do We reward those who do good. [Qur’an 28:14]

The Qur’anic phrase balagha ashuddah in the above verse has given rise to differences in interpretation of what exact age is meant by it. Furthermore, this phrase is conjoined with the word istawā meaning settled or firmly established. This suggests that the phrase balagha ashuddah wa istawā refers to a stage of Moses life in which he attained his full physical as well as spiritual/psychological strength. The commentators interpret this as bestowing of Prophethood on Moses and the corresponding age of 40 years (See the commentaries such as Tafsīr al-Ṭabarī, Tafsīr al-Qurṭubī, Tafsīr al-Jalalyn, Al-Kashshāf of al-Zamakhsharī, etc.).

Thirdly, after killing of one of the Egyptians, Moses immediately fled to Midian after learning that the officials in Egypt were planning to slay him. However, what is not clear is the time that elapsed between the conferment of wisdom and knowledge on Moses and his killing of the Egyptian.

When he reached full age, and was firmly established (in life), We bestowed on him wisdom and knowledge: for thus do We reward those who do good. And he entered the city at a time when its people were not watching: and he found there two men fighting,- one of his own religion, and the other, of his foes. Now the man of his own religion appealed to him against his foe, and Moses struck him with his fist and made an end of him.

He said: “This is a work of Evil (Satan): for he is an enemy that manifestly misleads!” He prayed: “O my Lord! I have indeed wronged my soul! Do Thou then forgive me!” So (Allah) forgave him: for He is the Oft-Forgiving, Most Merciful. He said: “O my Lord! For that Thou hast bestowed Thy Grace on me, never shall I be a help to those who sin!”

So he saw the morning in the city, looking about, in a state of fear, when behold, the man who had, the day before, sought his help called aloud for his help (again). Moses said to him: “Thou art truly, it is clear, a quarrelsome fellow!” Then, when he decided to lay hold of the man who was an enemy to both of them, that man said: “O Moses! Is it thy intention to slay me as thou slewest a man yesterday? Thy intention is none other than to become a powerful violent man in the land, and not to be one who sets things right!”

And there came a man, running, from the furthest end of the City. He said: “O Moses! the Chiefs are taking counsel together about thee, to slay thee: so get thee away, for I do give thee sincere advice.” He therefore got away therefrom, looking about, in a state of fear. He prayed “O my Lord! save me from people given to wrong-doing.” Then, when he turned his face towards (the land of) Madyan, he said: “I do hope that my Lord will show me the smooth and straight Path.” [Qur’an 28:14-22]

The events surrounding the conferment of wisdom and knowledge on Moses and his killing of the Egyptian in the Qur’an are mentioned successively suggesting that they were perhaps separated by a shorter period of time. As it stands, this period of time is an unknown. In Midian, Moses offered to help two girls to water their flocks. The father of the girls agreed to marry one of them to Moses under the condition that he serves him for 8 years and voluntarily for 2 more years to make it 10 years as stated in Qur’an 28:25-29.

Afterwards one of the (damsels) came (back) to him, walking bashfully. She said: “My father invites thee that he may reward thee for having watered (our flocks) for us.” So when he came to him and narrated the story, he said: “Fear thou not: (well) hast thou escaped from unjust people.” Said one of the (damsels): “O my (dear) father! engage him on wages: truly the best of men for thee to employ is the (man) who is strong and trusty”

He said: “I intend to wed one of these my daughters to thee, on condition that thou serve me for eight years; but if thou complete ten years, it will be (grace) from thee. But I intend not to place thee under a difficulty: thou wilt find me, indeed, if Allah wills, one of the righteous.” He said: “Be that (the agreement) between me and thee: whichever of the two terms I fulfill, let there be no ill-will to me. Be Allah a witness to what we say.”

Now when Moses had fulfilled the term, and was travelling with his family, he perceived a fire in the direction of Mount Tur. He said to his family: “Tarry ye; I perceive a fire; I hope to bring you from there some information, or a burning firebrand, that ye may warm yourselves.” [Qur’an 28:25-29]

It is not clear from the above verses if Moses fulfilled 8 or 10 years in Midian. In any case, we can take a minimum of 8-10 years as Moses’ stay in Midian.

Fourthly, there is no mention of an explicit length of Moses second sojourn in Egypt after returning from Midian. Nonetheless, there are number of verses in the Qur’an which can help to give us an idea of the length of time of Moses second sojourn in Egypt.

Said the chiefs of Pharaoh’s people: “Wilt thou leave Moses and his people, to spread mischief in the land, and to abandon thee and thy gods?” He said: “Their male children will we slay; (only) their females will we save alive; and we have over them (power) irresistible.” Said Moses to his people:

“Pray for help from Allah, and (wait) in patience and constancy: for the earth is Allah’s, to give as a heritage to such of His servants as He pleaseth; and the end is (best) for the righteous. They said: “We have had (nothing but) trouble, both before and after thou camest to us.” He said: “It may be that your Lord will destroy your enemy and make you inheritors in the earth; that so He may try you by your deeds.” We punished the people of Pharaoh with years (of droughts) and shortness of crops; that they might receive admonition. But when good (times) came, they said, “

This is due to us;” When gripped by calamity, they ascribed it to evil omens connected with Moses and those with him! Behold! in truth the omens of evil are theirs in Allah’s sight, but most of them do not understand! They said (to Moses): “Whatever be the Signs thou bringest, to work therewith thy sorcery on us, we shall never believe in thee.

So We sent (plagues) on them: Wholesale death, Locusts, Lice, Frogs, And Blood: Signs openly self-explained: but they were steeped in arrogance,- a people given to sin. Every time the penalty fell on them, they said: “O Moses! on your behalf call on thy Lord in virtue of his promise to thee: If thou wilt remove the penalty from us, we shall truly believe in thee, and we shall send away the Children of Israel with thee.”

But every time We removed the penalty from them according to a fixed term which they had to fulfil,- Behold! they broke their word! So We exacted retribution from them: We drowned them in the sea, because they rejected Our Signs and failed to take warning from them.

And We made a people, considered weak (and of no account), inheritors of lands in both east and west, – lands whereon We sent down Our blessings. The fair promise of thy Lord was fulfilled for the Children of Israel, because they had patience and constancy, and We levelled to the ground the great works and fine buildings which Pharaoh and his people erected (with such pride). [Qur’an 7:127-137]

Several pieces of information can be obtained from the above verses which suggest that Moses stayed in Egypt for a considerable period of time, measured in years. Firstly, the reference to the affliction of years of droughts and shortage of crops [Qur’an 7:131] and then a period of good time. Thus the people of Pharaoh had changing spells of bad and good fortune so that they might receive admonition. Instead they blamed Moses and his people for their calamities and claimed the good times were due to them. Secondly, plagues [Qur’an 7:133] themselves must have extended over a certain period of time. Thirdly, a catastrophe like a flood or swarm of locusts leaves effects, including indirect effects, that last for several months at least.[43]

(a)

(b)

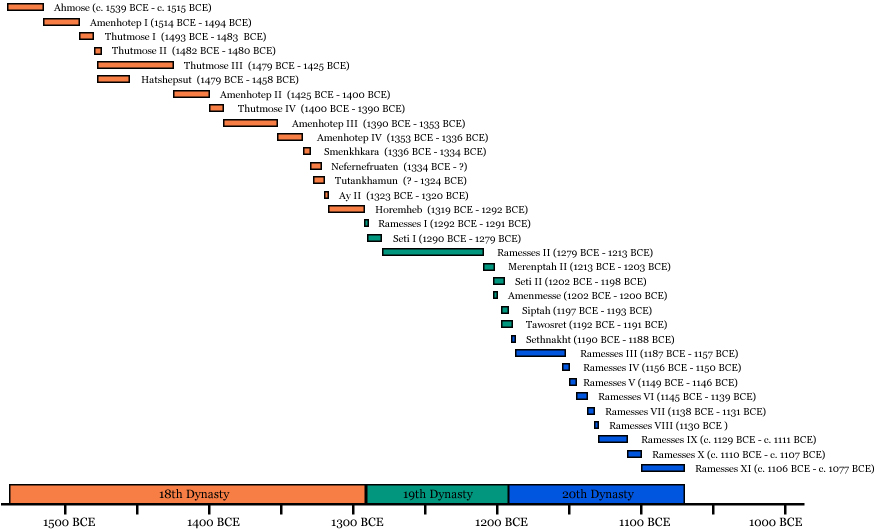

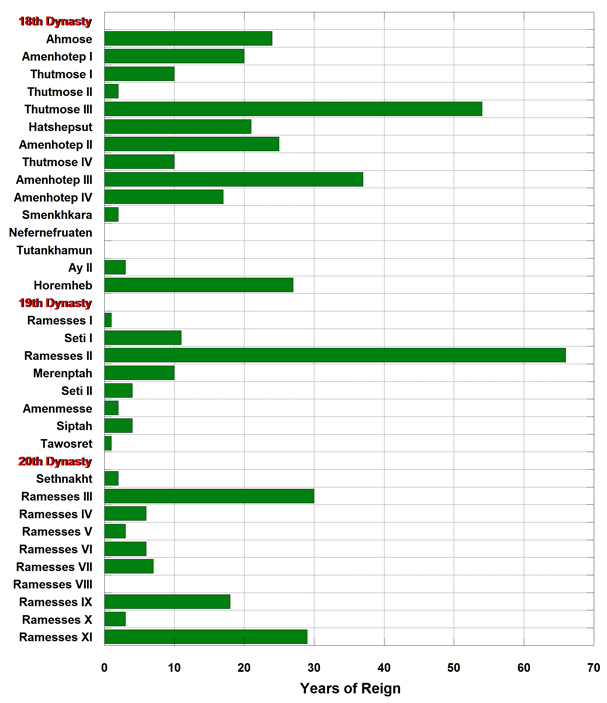

Figure 3: (a) The timeline of the New Kingdom Period in ancient Egypt and (b) the reign of rulers therein.[44]

Let us now recapitulate the time period of the reign of the Pharaoh during the time of Moses. Exclusively relying on data found the Qur’an and its commentaries, we have an account of 48-50 years of reign of the Pharaoh. This gives the minimum length of the reign of the Pharaoh. What is unaccounted for is the number of years that the Pharaoh reigned before Moses was born, the period between the conferment of wisdom and knowledge on Moses and his killing of the Egyptian, and the length of Moses second sojourn in Egypt after returning from Midian.

Using the data in hand, let us examine the length of the reign of the Pharaohs in the New Kingdom and the Third Intermediate Periods. Figures 3(a) and 3(b) give the timeline of the New Kingdom Period in ancient Egypt and the reign of rulers therein, respectively.

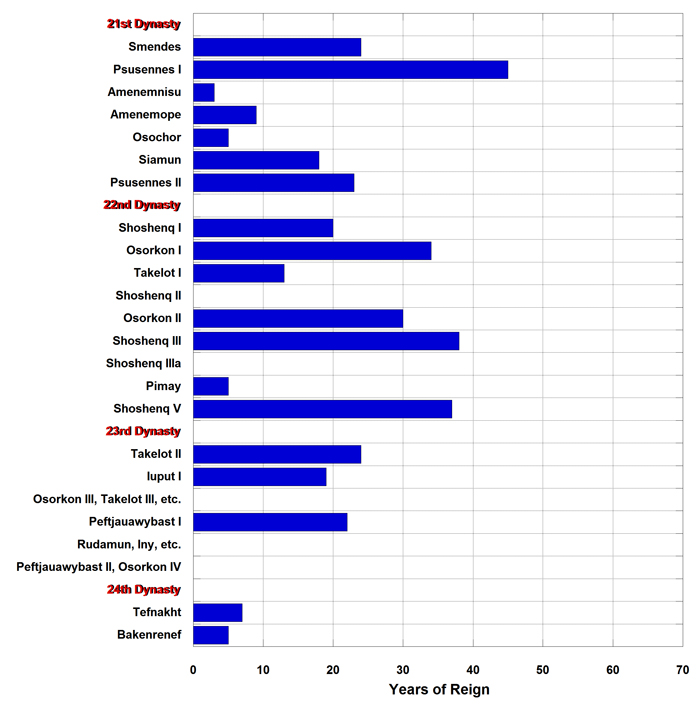

It is observed that the rulers of Egypt who had reigned for close to 50 years are Tuthmosis III (~54 years, 1479-1425 BCE) and Ramesses II (~66 years, 1279-1213 BCE). In the Third Intermediate Period, the rule of Psusennes I (~45 years, c. 1051-1006 BCE) comes close [Figure 4].

Figure 4: The length of reign of rulers in the Third Intermediate Period.[45]

If we consider the case of Tuthmosis III from the New Kingdom Period, we find that 4-7 years are not enough to account for the Pharaoh’s reign before Moses was born, the period between the conferment of wisdom and knowledge on Moses and his killing of the Egyptian, and the length of Moses second sojourn in Egypt after returning from Midian. Furthermore, there are other problems associated with this period too. Tuthmosis III was still a young child when he succeeded to the throne of Egypt after the death of his father Tuthmosis II (1482-1480 BCE). However, Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) was appointed regent due to the boy’s young age.

They ruled jointly until 1473 BCE when she declared herself a Pharaoh. She is shown dressed in men’s attire and administered affairs of the nation with the full support of important officials. Hatshepsut disappeared in 1458 BCE when Tuthmosis III, wanting to reclaim the throne, led a revolt. After Tuthmosis III became the sole ruler, he had her statues and reliefs mutilated. Thus the actual reign of Tuthmosis III was for only ~33 years.

It must be added that in the Late Period (c. 722-332 BCE) comprising of 25th and 26th Dynasties and later the Persians and then the Romans, there existed no ruler who could match the length of reign of Ramesses II. The longest reign during the Late Period was that of Psamtik I (~54 years, 664-610 BCE).[46] This is a very late and improbable date for the Exodus and the length of reign suffers from similar problems as that with Tuthmosis III (i.e., without considering the issue of coregency with Hatshepsut) discussed earlier. That leaves us only with Ramesses II.

As mentioned earlier, Ramesses II ruled for the longest period of time as compared to any other Pharaoh – a total of ~66 years. To this we can also add Ramesses II’s proposed co-regency with this father Seti I which lasted for about 1 to 2 years before the former formally assumed the duties of rulership of Egypt after the latter’s death.[47] This would extend the reign of Ramesses II to around 68 years.

Kitchen and others prefer not to talk of co-regency but of prince-regency which meant Ramesses II had all the attributes of kingship, including his own harem, except his own regnal years.[48] Whatever the case may be we can account for 48-50 years of his reign from the Qur’an.

We are still left with about 18-20 years of Ramesses II’s reign before his death, which can be used to account for the Pharaoh’s reign before Moses was born, the period between the conferment of wisdom and knowledge on Moses and his killing of the Egyptian, and the length of Moses second sojourn in Egypt after returning from Midian.

Thus with the available evidence Ramesses II appears to fit well with the statements mentioned in the Qur’an. In order to further strengthen the case that the Qur’an indeed speaks of Pharaoh Ramesses II, let us look at the supporting evidence from the Qur’an and see if it fits the description of Ramesses II of history.

THE PHARAOH AS THE PRINCIPAL GOD OF ANCIENT EGYPT

One of the principal themes which appear in the Qur’an in the story of Moses is that of Pharaoh claiming himself to be the principal god. Does Ramesses II fit the description of a Pharaoh who claimed to be principal god of Egypt? Let us investigate.

When Moses calls Pharaoh to worship one true God, the call is rejected. Instead Pharaoh collects his men and proclaims that he is their Lord, most high.

Has the story of Moses reached thee? Behold, thy Lord did call to him in the sacred valley of Tuwa, “Go thou to Pharaoh for he has indeed transgressed all bounds: And say to him, ‘Wouldst thou that thou shouldst be purified (from sin)? – And that I guide thee to thy Lord, so thou shouldst fear Him?'” Then did (Moses) show him the Great Sign. But (Pharaoh) rejected it and disobeyed (guidance); Further, he turned his back, striving hard (against God). Then he collected (his men) and made a proclamation, Saying, “I am your Lord, Most High”. [Qur’an 79:15-24]

Furthermore, when Moses goes to Pharaoh with clear signs, they are rejected as being “fake”. Pharaoh then addresses his chiefs by saying that he knows of no god for them except him.

Pharaoh said: “O Chiefs! no god do I know for you but myself… [Qur’an 28:38]

The last statement comes in connection with the victory of Prophet Moses. Since the setting of the story of Moses and Pharaoh in the Qur’an is in the New Kingdom Period, it is worthwhile mentioning one of the characteristics in this period was deification of the Pharaohs and how it started to become the norm.

By the early New Kingdom, deification of the living king had become an established practice, and the living king could himself be worshipped and supplicated for aid as a god.[49]

During the time of Ramesses II, the deification of the Pharaoh reached its peak as evidenced in numerous cult statues as well as supporting hieroglyphs and papyri.[50] The hieroglyphs give good information about the him. Let us consider three hieroglyphs from the time of Ramesses II (who had prenomen Usermaatre-setepenre and nomen Ramesses meryamun).

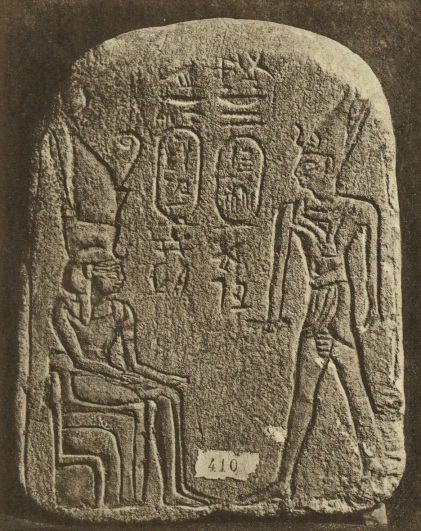

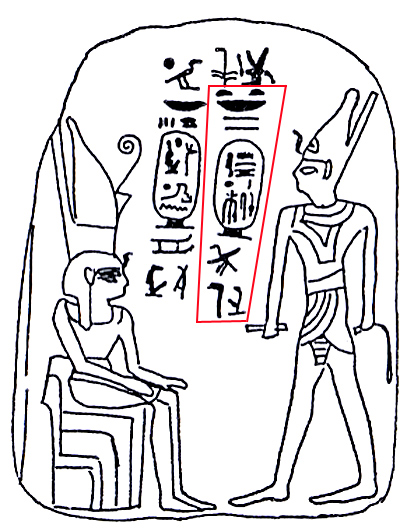

Stela no. 410 of Hildesheim Museum shows two people, one is standing wearing the double crown with the uraeus, a short skirt, a necklace and holds the so-called handkerchief or seal in one hand [Figure 5(a)]. He is called: “King of Upper and Lower Egypt, the Lord of the Two Lands ‘Ramesses-meryamun, the God’”.[51]

|  | |

| (a) |

| ||

| (b) |

(c)

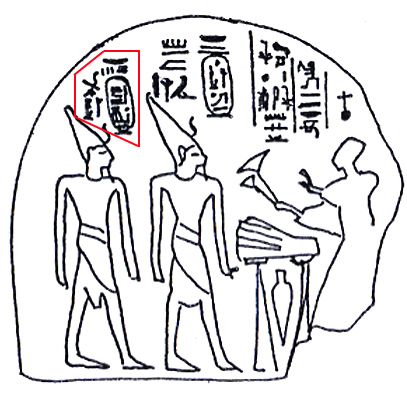

Figure 5: Stela no. (a) 410, (b) 1079 of the Hildesheim Museum. (c) These have an important inscription saying “Ramesses-meryamun, the god”. This inscription is marked inside a red box in both the stelas (a) and (b).[52]

On stela no. 1079 of Hildesheim Museum a man is depicted wearing a long garment tied at the waist, offering two flowers with his right hand. In front of him is a table laden with various kinds of offerings, and two stands with a vase between them [Figure 5(b)]. Opposite him are two statues, each wearing a short kilt, an artificial beard and the crown of Upper Egypt, with uraeus in front. Above these two statues and before them are the words: “Lord of the two Lands ‘Usermaatre-setpenre’ Monthu-in-the-Two-Lands” and “Lord of the diadems ‘Ramesses-meryamun’, the God”.[53]

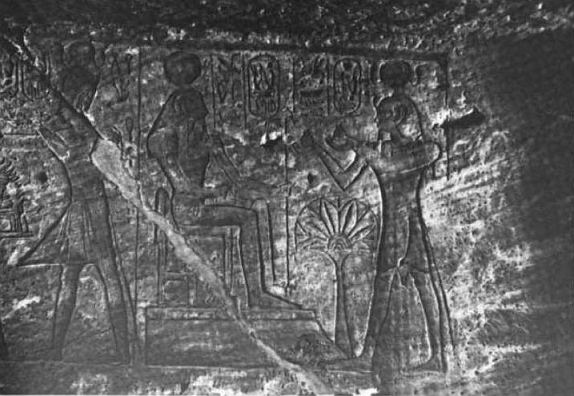

Figure 6: A relief in the Great Temple of Abu Simbel showing Ramesses II venerating Ramesses II.[54]

Our last example of the divine kingship in ancient Egypt comes from the Great Temple at Abu Simbel [Figure 6]. An interesting relief in the Great Temple of Abu Simbel shows the “Lord of Two Lands ‘Usermare-setpenre’” (= Ramesses II) offering to “Ramesses-meryamun” (= Ramesses II). Obviously, Ramesses II is worshipping Ramesses II here. However, we also note that the worshipper and the one who is worshipped have two different names and that these names are pronomen and nomen of Ramesses II, respectively.

A closer look at the iconography reveals that the worshipper and he who is worshipped are not identical. He, to whom the offering is made, is adorned with a sun-disk and has a curved horn around his ear, depicting his divinity. Therefore, Ramesses II is not simply worshipping himself, but his divine self.[55] Concerning the Pharaoh, the Qur’an also mentions that he exalted himself in the land and that he was extravagant.

But none believed in Musa except the offspring of his people, on account of the fear of Pharaoh and their chiefs, lest he should persecute them; and most surely Pharaoh was lofty in the land [Arabic: firʿawn la-ʿālin fi-al-ardh]; and most surely he was of the extravagant [Arabic: innahu lamin al-musrifīn]. [Qur’an 10:83]

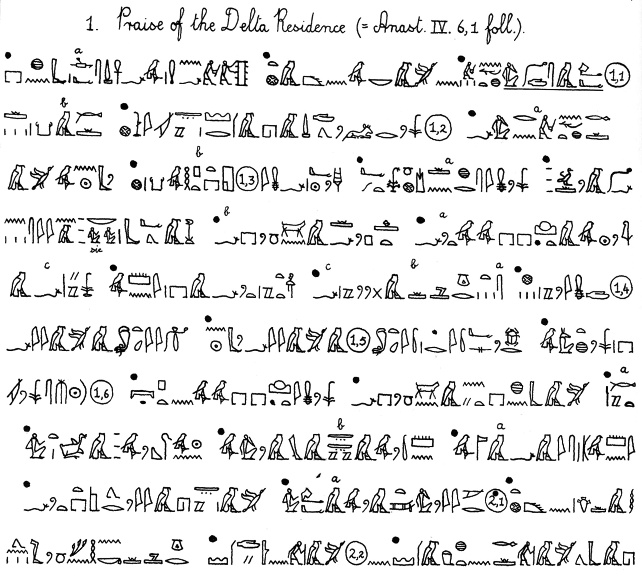

We have already seen how Ramesses II exalted himself as the principal god of Egypt. What are the other ways he could have exalted himself? The answer to this question comes from Papyrus Anastasi II dated to the time of Merneptah, successor of Ramesses II.[56] Papyrus Anastasi II begins by “Praise of the Delta Residence” of the Ramesside kings. The textual content of this section is similar to that of Papyrus Anastasi IV, (6,1-6,10). What is interesting in this papyrus is the mention of exalted position of Ramesses II.

(1,1) Beginning of the Recital of the Victories of the Lord of Egypt. His Majesty (l.p.h) has built himself a castle whose name is Great-of-Victories. (1,2) It lies between Djahy and To-meri, and is full of food and victuals. It is after the fashion of On of Upper Egypt, and its duration is like (1,3) that of He-Ka-Ptah.

The sun arises in its horizon and sets within it. Everyone has foresaken his (1,4) (own) town and settled in its neighbourhood. Its western part is the House of Amun, its southern part the House of Seth. Astarte is (1,5) in its Levant, and Edjo in its northern part. (1,6) Ramesse-miamum (l.h) is in it as god, Mont-in-the-Two-Lands as herald, Sun-of-Rulers as vizier, Joy-of-Egypt (2,1) Beloved-of-Atum as mayor. The country has gone to its proper place.[57]

Here we see Ramesses II in exalting himself in four different aspects, viz., as god, herald, vizier and mayor. This is as if to show that he was everything to the capital, and commanded everything.

Figure 7: Portrayal of Ramesses II as the living god at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel.

How was Ramesses II extravagant? The Arabic word musrifīn is derived from the root sarafa which means “to exceed all bounds, be immoderate, be extravagant…; to waste, squander, dissipate, spend lavishly”.[58] In order to promote himself as the living god, Ramesses II built colossal monuments throughout Egypt, which he furnished with numerous large-scale images of himself.

Perhaps the best example of his extravagant ways to promote his divinity comes from the Great Temple at Abu Simbel where Ramesses II is depicted as god, and the deity Re-Horakhty is portrayed on a diminutive scale in the centre of the king’s four colossal statues [Figure 7].

It is here, the cult of the living god was practiced.[59] Thus, Ramesses II appears to fit the Qur’anic description of the Pharaoh who exalted himself and was extravagant in his ways to depict himself as a divinity. The issue of Ramesses II building colossal structures brings us to another important statement made in the Qur’an concerning the Pharaoh – he is called the Pharaoh of the awtād or Lord of the stakes.

The Qur’an provides another very unique and interesting description of the Pharaoh which can be shown to be particularly applicable to Ramesses II. This is the Qur’anic reference to Pharaoh in a couple of verses as dhul-awtād (“of the awtād” or usually translated as “Lord of the stakes”). The relevant verses are:

Or have they the dominion of the heavens and the earth and all between? If so, let them mount up with the ropes and means (to reach that end)! But there – will be put to flight even a host of confederates. Before them (were many who) rejected messengers,- the people of Noah, and ‘Ad, and Pharaoh, the Lord of Stakes, and Thamud, and the people of Lut, and the Companions of the Wood; – such were the Confederates. [Qur’an 38:10-13]

Seest thou not how thy Lord dealt with the ‘Ad (people),- Of the (city of) Iram, with lofty pillars, the like of which were not produced in (all) the land? And with the Thamud (people), who cut out (huge) rocks in the valley? – And with Pharaoh, lord of stakes? (All) these transgressed beyond bounds in the lands, and heaped therein mischief (on mischief). Therefore did thy Lord pour on them a scourge of diverse chastisements. [Qur’an 89:6-13]

The commentators of the Qur’an have put forth different views for the meaning of the Qur’anic description of the Pharaoh as dhul-awtād (“of the awtād“), as the word awtād, plural of watad, has different meanings. The opinion which attracted most agreement is that the Pharaoh used the stakes to torture and crucify his opponents, especially those who abandoned him and converted to the religion of Moses. Perhaps the widest possible interpretation of Qur’an 38:12 comes from al-Qurṭubī. He says in his commentary of Qur’an 38:12:

ولم يقل ذكرها؛ لأنه لما كان المضمر فيه مذكراً ذكره؛ وإن كان اللفظ مقتضياً للتأنيث. ووصف فرعون بأنه ذو الأوتاد. وقد ٱختلف في تأويل ذلك؛ فقال ٱبن عباس: المعنى ذو البناء المحكم. وقال الضحاك: كان كثير البنيان، والبنيان يسمى أوتاداً. وعن ٱبن عباس أيضاً وقتادة وعطاء: أنه كانت له أوتاد وأرسان وملاعب يُلْعَب له عليها. وعن الضحاك أيضاً: ذو القوّة والبطش. وقال الكلبي ومقاتل: كان يعذِّب الناس بالأوتاد، وكان إذا غضب على أحد مدّه مستلقياً بين أربعة أوتاد في الأرض، ويرسل عليه العقارب والحيات حتى يموت. وقيل: كان يشبح المعذب بين أربع سوارٍ؛ كل طرف من أطرافه إلى سارية مضروب فيه وَتَد من حديد ويتركه حتى يموت. وقيل: ذو الأوتاد أي ذو الجنود الكثيرة فسميت الجنود أوتاداً؛ لأنهم يقوّون أمره كما يقوّي الوتد البيت. وقال ٱبن قتيبة: العرب تقول هم في عزّ ثابت الأوتاد، يريدون دائماً شديداً

… He described Pharaoh as (the lord) of the stakes. This statement received various interpretations. Ibn ʿAbbās said: It means the lord of the secure building. Al-Ḍaḥḥāk said: He owned many buildings; buildings are called awtād. Also according to Ibn ʿAbbās as well as Qatādah and ʿAṭāʾ: He owned stakes and ropes and playgrounds where he was entertained. According to al-Ḍaḥḥāk also (it means):

the one who has strength and strong hand. Al-Kalbī and Muqātil said: He used to torture people with the stakes. When he got angry with someone, he would lay him down on the ground and fasten him to four stakes. Then he would release scorpions and snakes onto him until he died. It was also said: he would stretch the tortured between four pillars, each of his limbs would be nailed to that pillar with an iron stake and he would be left to die.

It was also said: the lord of the stakes means the lord of many soldiers where the soldiers were called stakes because they uphold his command like the stakes uphold the house. Ibn Qutaybah said: The Arabs say, “their power has got stable stakes”, meaning that it is strong and permanent.

The meaning which we are concerned with here is the description of the Pharaoh being “of the buildings”. The Qur’an’s choice of this phrase could not have been more accurate. This is what distinguishes Ramesses II from all other Pharaohs. Ramesses II was involved in more building projects than any other Pharaoh throughout the history of ancient Egypt. Commenting on Ramesses II’s incredible obsession with building, Kitchen notes that:

He desired to work not merely on the grand scale – witness the Ramesseum, Luxor, Abu Simbel, and the now vanished splendours of Pi-Ramesse – but on the widest possible front as the years passed…. But certainly in his building works for the gods the entire length of Egypt and Nubia, Ramesses II surpassed not only the Eighteenth Dynasty but every other period in Egyptian history. In that realm, he certainly fulfilled the dynasty’s aim for satiety.[60]

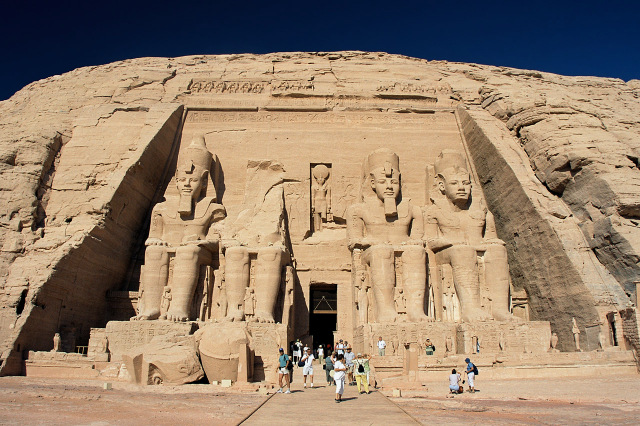

Similarly, Clayton acknowledges Ramesses II as a pre-eminent builder among the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt and states that his greatest feat was the building of two temples at Abu Simbel, especially the Great Temple.

As a monument builder Ramesses II stands pre-eminent amongst the pharaohs of Egypt. Although Khufu had created the Great Pyramid, Ramesses’ hand lay over the whole land. True, he thought nothing of adding his name to other kings’ monuments and statues right back to the Middle Kingdom, so that nowadays the majority of cartouches seen on almost any monument proclaim his throne name – User-maat-re (‘the justice of Re is strong’).

Yet his genuine building achievements are on a Herculean scale. He added to the great temples at Karnak and Luxor, completed his father Seti’s mortuary temple at Gourna (Thebes) and also his Abydos temple, and built his own temple nearby at Abydos. On the west bank at Thebes he constructed a giant mortuary temple,

the Ramesseum. Inscriptions in the sandstone quarries at Gebel el-Silsila record at least 3000 workmen employed there cutting the stone for the Ramesseum alone. Other major mortuary temples rose in Nubia at Beit el-Wali, Gerf Hussein, Wadi es Sebua, Derr and even as far south as Napata.

Ramesses’ greatest building feat must be counted not one of these, but the carving out of the mountainside of the two temples at Abu Simbel in Nubia. The grandeur of the larger, the Great Temple, is overwhelming, fronted as it is by four colossal 60-ft (18-m) high seated figures of the king that flanked the entrance in two pairs.

It is strange to reflect that whilst the smaller temple, dedicated to Hathor and Ramesses’ favourite queen Nefertari, has lain open for centuries, the Great Temple was only discovered in 1813 by the Swiss explorer Jean Louis Burckhardt and first entered by Giovanni Belzoni on 1 August 1817.

A miracle of ancient engineering, its orientation was so exact that the rising sun at the equinox on 22 February and 22 October flooded directly through the great entrance to illuminate three of the four gods carved seated in the sanctuary over 200 ft (60 m) inside the mountain (the fourth of the seated gods, Ptah, does not become illuminated as, appropriately, he is a god associated with the underworld).[61]

It is also worth noting that the phrase “Pharaoh, Lord of the awtād” is mentioned along with Iram which had lofty pillars, most likely cut from rocks, and people of Thamud who built houses in the mountains. This suggests that Pharaoh Ramesses II also did something similar, i.e., built structures out of rocks. Indeed Ramesses II built two temples at Abu Simbel in Nubia which were cut in the living rock of the mountainside [Figure 8].

One is called the Great Temple, a huge building with four colossal statues of seated figures of Ramesses II, about 20 meters high, flanking its entrance. The other is the Small Temple dedicated to Hathor and Nefertari, about one hundred meters northeast of the Great Temple of Ramesses II and was dedicated to the goddess Hathor and Ramesses II’s chief consort, Nefertari.

These temples are considered to be Ramesses II greatest building achievements. Since Ramesses II wanted to eternalize himself, he also ordered changes to the methods used by his masons. Unlike the shallow reliefs of previous Pharaohs which could easily be transformed, with their images and words easily erased, Ramesses II had had his carvings deeply engraved in stone, which made them less susceptible to alterations.

Figure 8: The Great Temple (left) and the Small Temple (right) at Abu Simbel.

To understand the importance of the two temples at Abu Simbel, it is worthwhile adding that the UNESCO made an international appeal between 1960 and 1980 to save the monuments in Nubia when they were threatened by submergence as a result of the Aswan High Dam.

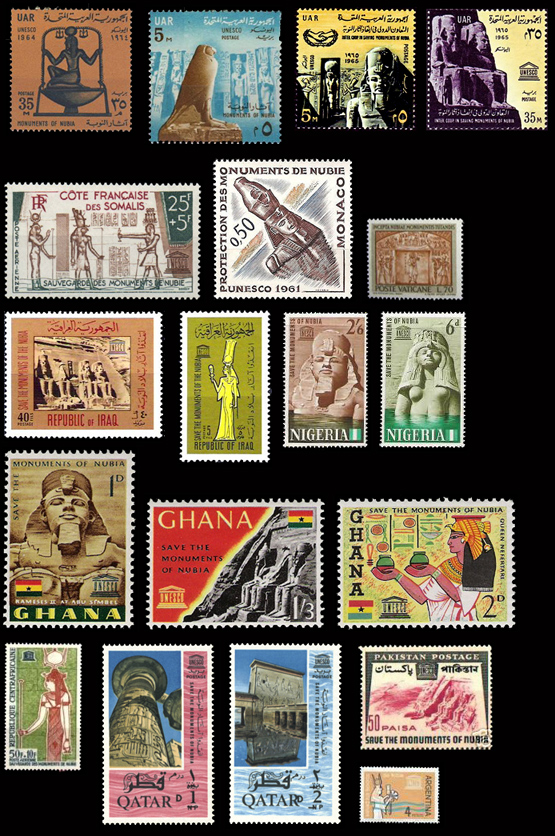

The response to the appeal came fast and the international community contributed money and effort to relocate the historic sites. To create a worldwide awareness for saving the Nubian monuments, a philatelic campaign featuring the temples at Abu Simbel, Ramesses II and his queen Nefertari was launched in which numerous countries participated [Figure 9].[62]

The operation, inter alia, included dismantling Abu Simbel Temple, and moving it to another area to be reassembled once again. Abu Simbel Temple was completely dismantled to 1036 pieces, each with average of 7 to 30 tons, as they were rebuilt on the top of the mountain overlooking the genuine spots, drawn by the ancient Egyptians 3,000 years ago. It is not surprising that the operation of saving the Nubian monuments was described as the greatest in the history of saving monuments.

Figure 9: A philatelic melange showing the campaign to create worldwide awareness to save the antiquities of Nubia. Ramesses II and his temples at Abu Simbel were prominently featured on the stamps in many countries. Some stamps also show his queen Nefertari.

In the above figure, the are stamps from (from top row, left to right) Egypt (UAR), Somalia, Monaco, the Vatican, Iraq, Nigeria, Ghana, Republic of Central Africa, Qatar, Pakistan and Argentina. Other countries such as Morocco, Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast), Guatemala, Gabon, Maladive Islands, Republic of Guinea among others also issued stamps.[63]

Apart from the Great Temple at Abu Simbel, the city of Pr-Ramesses founded by Ramesses II must stand out as one of the most ambitious construction efforts the world has ever known. Previously Pr-Ramesses had been variously placed at Tell er-Retabeh, Pelusium, Tanis and Tehel in Lower Egypt.[64] However, archaeological excavations by the Egyptian scholars Labib Habachi and Mahmoud Hamza identified modern day city Khatana-Qantir as the prime candidate [Figure 10].[65] Subsequently due to the joint cooperation of the Egyptian Antiquities Organisation,

the Austrian mission headed by Manfred Bietak of the university of Vienna and the German mission headed by Edgar Pusch of the Pelizaeus Museum, modern archaeological investigations also converge on the city of Qantir/Tell el-Dab’a[66] which is in agreement with the descriptions of Pr-Ramesses gathered from the literary evidence and other primary and secondary sources from that period.

Figure 10: Location of Pithom and Pi-Ramesses in the Nile delta region.

Uphill noted the following nine key features of Pr-Ramesses from said sources including: a city containing monuments naming Pr-Ramesses, a central position for royal residence and governance, access route to Asia for the armies, suitably large area for correspondingly large population, suitable for the core functions of the Army such as headquarters etc., monuments of Ramesses II, relevant deities present, scale of site and monuments adequate and containing a river port.[67] In the timeline of the ancient near east, the construction of Pr-Ramesses is certainly unprecedented as Uphill informs us,

Per Ramesses was probably the vastest and most costly royal residence ever erected by the hand of man. As can now be seen its known palace and official centre covered an area of at least four square miles, and its temples were in scale with this, a colossal assemblage forming perhaps the largest collection of chapels built in the pre-classical world by a single ruler at one time.[68]

With the use of a caesium magnetometer, the first geophysical measurements of Pr-Ramesses took place in 1996.[69] Using the data gathered from the recent magnetometer inspections, the latest projections have shown the city centre/royal residence comprised at least 10 square kms, around 3.5 square kms more than had been previously estimated. It is hoped that continued magnetic investigation will eventually lead to a map of Pr-Ramesses covering at a minimum the city centre/royal residence.[70]

With all the focus on the city centre/royal residence, one should also not forget to consider the large suburban zone, which, when factored into the calculations, shows the ancient city of Pr-Ramesses comprised at least 30 square kms.[71] Sometimes numbers alone do not convey the sheer scale of the construction.

If we consider the area of Pr-Ramesses in comparison to other celebrated cities in the ancient near east such as the famous ancient Mesopotamian cities of Khorsabad, Nimrud, Nineveh and Babylon, the area bounded by Pr-Ramesses easily eclipses them all.[72] Commenting on such a gigantic feat of human engineering Uphill further remarks,

The unique feature about Per Ramesses is that it is the only city of imperial size in the ancient near east, rivalling Heliopolis, Memphis and Thebes in splendour, known to have been entirely planned, built and fully completed under one King.[73]

Pr-Ramesses, which once had magnificent splendour, now lies in ruins. Most likely, the destruction of this magnificent city is alluded to in the Qur’an 7:137 and God knows best:

And We made a people, considered weak (and of no account), inheritors of lands in both east and west, – lands whereon We sent down Our blessings. The fair promise of thy Lord was fulfilled for the Children of Israel , because they had patience and constancy, and We levelled to the ground the great works and fine buildings which Pharaoh and his people erected (with such pride) [mā kāna yaṣnaʿu firʿawna wa qawhumū wa mā kānū yaʿrishūn]. [Qur’an 7:137]

God says that He levelled to the ground the great works and fine buildings which Pharaoh and his people erected. It is interesting this verse is tied to the period of weakness of the Children of Israel which they endured with patience and steadfastness; the time when they were under Pharaoh, toiling for him. From the discussion, it is undoubtedly clear that Ramesses II fits the description of the Pharaoh of the awtād.

“THIS DAY SHALL WE SAVE YOU IN THE BODY, THAT YOU MAYEST BE A SIGN TO THOSE WHO COME AFTER YOU…”

We took the Children of Israel across the sea: Pharaoh and his hosts followed them in insolence and spite. At length, when overwhelmed with the flood, he said: “I believe that there is no god except Him Whom the Children of Israel believe in: I am of those who submit (to Allah in Islam).” (It was said to him): “Ah now!- But a little while before, wast thou in rebellion!- and thou didst mischief (and violence)! “This day shall We save thee in the body, that thou mayest be a sign to those who come after thee! but verily, many among mankind are heedless of Our Signs!” [Qur’an 10:90-92]

The Qur’an and the Bible [Exodus 14:21-30 and Exodus 15:19-21] state that the Pharaoh was drowned in the sea. However, the Qur’an differs from the Bible and it makes a very unique statement that the body of the drowned Pharaoh was saved as a sign for future generations. The Qur’anic statement about rescuing Pharaoh’s body would be in total agreement with the fact that the body of Ramesses II has survived in a mummified form.

It was discovered in 1881 among a group of royal mummies that had been removed from their original tombs for fear of theft. Priests of the 21st Dynasty had reburied them in a cache at Deir al-Bahari on Luxor’s west bank.[74] The mummy of Ramesses II formed one of the cache and its resting place was Tomb KV7 in the Valley of Kings. Nothing whatsoever was known at the time of the revelation of the Qur’an about the mummy of Ramesses II.

A few words also need to be said about the preservation of the mummy of Ramesses II [Figure 11]. In 1974, Egyptologists at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, noticed that the mummy’s condition was worsening rapidly. They decided to fly Rameses II to Paris so that a team of experts could give the mummy a medical examination.

On September 26, 1976, a French Air Force plane touched down at Le Bourget airport just outside Paris carrying the mummified body. Ramesses II may have been dead for more than 3,000 years but his mummified body was welcomed with a ceremony fit for any living head of state.

(a)

(b)

Figure 11: Mummy of Ramesses II showing (a) top and (b) side views.

The idea of bringing the mummy of Ramesses II to Paris for an exhaustive scientific investigation was the brainchild of Dr. Maurice Bucaille. The project was co-directed by Christiane Desroche-Noblecourt, curator of Egyptian Antiquities at the Musée du Louvre, and Professor Lionel Balout, Director of the Musée de l’Homme.[75] One of goals of the project was to study the remains of the Pharaoh’s mummy for evidence that would complement that from other archaeological and written sources.

However, the main mission was to rescue the mummy from physical deterioration caused by fungus, bacteria and insects.[76] During the examination, scientific analysis revealed battle wounds and old fractures, as well as other medical conditions. From the x-ray analysis, it was concluded that Ramesses II was suffering from atherosclerosis and an x-ray of his pelvis showed calcification of both femoral arteries.[77]

In the last decades of his life, Ramesses II was apparently crippled with arthritis and walked with a hunched back.[78] It was suggested that Ramesses II suffered from ankylosing spondylitis, now part of rheumatologic folklore.[79] All these led Bucaille to infer that Ramesses II could have not played any role in the Exodus as he was crippled.[80] He claimed, using the biblical data (Exodus 2:23), that his son Merenptah was the Pharaoh involved in the Exodus after Ramesses II’s death. However, a recent study using better x-ray imaging and unpublished radiographs has concluded that the diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis as reported in the literature is unsupported.

The authors prefer a diagnosis of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis[81] (or DISH) which is corroborated by the archaeological and historical studies about the physical attributes and exploits of Ramesses II.[82] Thus, the possibility cannot be rejected out of hand that Ramesses II was the Pharaoh who perished in the sea while chasing the Children of Israel.[83]

However, it must be emphasized that the process of mummification itself convolutes the information of actual cause of death. Therefore, the cause of death of Ramesses II can’t be verified from his mummy.

God refers in the Qur’an to many peoples whom He had punished, for example, of ‘Ad and Thamud (Qur’an 29:38, 27:51-52), and whom He made signs for later generations. However, with the sole exception of Pharaoh, God never stated that He would save the bodies of those people and make their bodies signs for future generations.

In the case of Pharaoh’s body being saved for future generations, this is a statement which is not just confined to the people of Egypt or to those who lived at that time, but to all people who came after him. The mummy of Ramesses II is available even today for people from everywhere to see at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

MORE EGYPTIAN MISCELLANIES FROM THE QUR’AN

There are other details too which the Qur’an mentions about the Pharaoh. However, the identification of these using the ancient Egyptian history remains elusive or incomplete. For example, the Qur’an says that the Pharaoh had companions called Haman and Qarun. The name Haman was alleged to be a historical contradiction in the Qur’an because the Bible places it in the story of Esther.

Notwithstanding the flawed logic of using a fictitious book to find a historical character, it was noted that Haman may be simply an Arabized version of the ancient Egyptian amana. The ancient Egyptian deity ’IMN (or amana) was used in the title for a High Priest as well as an architect.

It would be akin to the king who ruled during the time of Moses being called firʿawn which is the Arabized form of the ancient Egyptian word “per-aa”, the title used to refer to the king of Egypt from the New Kingdom Period onwards. Should our proposed identification of Ramesses II be correct, a historical investigation has shown that Bakenkhons, the High Priest of Amun during Ramesses II reign, can be considered a good candidate for Haman mentioned in the Qur’an.

Another interesting detail which the Qur’an mentions is the day of encounter between Moses and the magicians.

“But we can surely produce magic to match thine! So make a tryst between us and thee, which we shall not fail to keep – neither we nor thou – in a place where both shall have even chances.” Moses said: “Your tryst is the Day of the Festival [yaum al-zīna], and let the people be assembled when the sun is well up.” [Qur’an 20:58-59]

The day of the encounter in the Qur’an is called yaum al-zīna. Zīna means a thing with which or by which one is adorned, ornamented, decorated, etc.[84] So, the phrase yaum al-zīna can mean a day when people are dressed up smartly, or the city is adorned or perhaps both. It could even mean a day of pompous celebration or more precisely a day of festival.[85] Could it refer to the Heb-Sed (or simply Sed) festival?

The Heb-Sed Festival,[86] also called a jubilee, was usually celebrated 30 years after a king’s rule and thereafter, every three years. Ramesses II celebrated a record 11 or 12 of these after his Heb-Sed festival in year 30. It was to renew the potency of the Pharaoh and to assure a long reign in the afterlife. One of the most important aspects of this festival is that it was probably witnessed by ordinary citizens only very rarely.

4. Conclusions

Those Christian scholars who date the Exodus can be broadly divided into two groups: one which believes that the Bible should be the sole basis of dating and the other group which uses ancient near eastern archaeology. Both these groups employ certain assumptions and overlook certain details in order to reach their conclusions. As we have observed, proving the efficacy of the statements contained in the Old Testament is problematic.

The biblical account is inherently contradictory as the information provided simultaneously points towards divergent time periods and thus divergent Pharaohs. The Christian scholars, whom the missionaries and apologists depend upon, rush to explain away these contradictions by making ingenious reinterpretations of the text and using concepts such as “editorial updating” and its corollary “inspired textual updating”.

For example, the number 480 does not actually stand for 480 and the place name Ramesses does not actually stand for the place name Ramesses. Does it really matter? Realising they have no other choice, the missionaries and apologists have long since approved “editorial updating” and its occurrence throughout the Bible. One such missionary casually states, “In the final anylsis, I do not mind if the place/person names were updated in Scriptures” – which begs the question what other texts the missionaries and apologists “do not mind” being updated?

It should be clear by now that such approval is integrated within a flexible creedal system of beliefs where one can believe in an undelineated Bible that contains errors and still maintain ones right to “salvation”. Consequently, the doctrines of biblical inspiration, infallibility and inerrancy become confusing and ineffectual as numbers mean other different numbers and place names mean other different place names.

Although certain assumptions must be formed in absence of information supplied, interpreting the Qur’an does not require one to depend upon “editorial updating”, “inspired textual updating”¸ assigning different numerical values to mysterious numbers or deciding between which type of manuscripts and translations to rely upon to calculate those numbers.

The Qur’an does not mention the name of the Pharaoh who unjustly oppressed Moses and the Children of Israel. When combined, the information provided by the Qur’an and the ancient Egyptian sources including the archaeological and documentary evidence, there are a sufficient number of clues that point towards the New Kingdom period in general and to the Pharaoh Ramesses II in particular who reigned for about 66 years from 1279–1213 BCE.

Although the scientific examination of Ramesses II’s mummy is inconclusive regarding the precise nature of his death, he did not, as was previously thought, have a debilitating rheumatic condition that would have physically prevented him from engaging Moses and the Children of Israel in the final stages of his life.