On The Textual Sources Of The New International Version (NIV) Bible

Mohamad Mostafa Nassar

Twitter:@NassarMohamadMR

1. Introduction

The New International Version (NIV) of the Bible, produced during the 1960s and 1970s by a committee of more than one hundred scholars, has become the preeminent translation trusted by millions of Christians worldwide. The goal of this translation was to convey in modern English the message of the Bible’s original authors.

The success of the NIV Bible can be seen in the fact that in each year since 1987 it has outsold the classic King James Version (KJV) Bible. Given such a smashing success of the NIV Bible, some people have seen the “invisible” hand of Trinitarian deity in its success and started to consider it as the “word” of God. This is very similar to what some people have felt about the KJV Bible. It is worth noting that the belief in the virtual inspiration and divine preservation of any translation has no basis in Christian theology.

The success of the NIV Bible also found its detractors. Some have called the New International Version as the New International Perversion. Our aim, however, is not to look into reasons for the NIV Bible’s success or the arguments of its detractors. Nor are we interested in bogus debates such as the NIV versus the KJV Bible because they are simply translations whether in modern or in the Jacobean English.

Our aim is to look into the textual sources used in the translation of the NIV Bible. Are they, what Christians claim to be the “Word” of God? Do they qualify as the “Word” of God? If not, then why not? In this article, we will show that the textual sources used in the translation of the NIV Bible are “eclectic”. These “eclectic” sources do not represent either the “original” text or the “inspired” text.

2. The NIV Bible On Its Textual Sources

What sources does the NIV Bible use for its translation? It is instructive to read what the Preface of the NIV Bible says. According to the Preface, the textual sources for the Old Testament in the NIV Bible are:

For the Old Testament the standard Hebrew text, the Masoretic Text as published in the latest editions of Biblia Hebraica, was used throughout. The Dead Sea Scrolls contain material bearing on an earlier stage of Hebrew text. They were consulted, as were the Samaritan Pentateuch and the ancient scribal traditions relating to textual changes. Sometimes a variant Hebrew reading in the margin of the Masoretic Text was followed instead of the text itself. Such instances, being variant within the Masoretic tradition, are not specified by footnotes.

In rare cases, words in the consonantal text were divided differently from the way they appear in the Masoretic Text. Footnotes indicate this. The translators also consulted the more important early versions – the Septuagint; Aquila, Symmachus and Theodotion; the Vulgate; the Syriac Peshitta; the Targums; and for the Psalms the Juxta Hebraica of Jerome.

Readings from these versions were occasionally followed where the Masoretic Text seemed doubtful and where accepted principles of textual criticism showed that one or more of these textual witnesses appeared to provide the correct reading. Such instances are footnoted. Sometimes vowel letters and vowel signs did not, in the judgment of the translators, represent the correct vowels for the original consonantal text. Accordingly some words were read with a different set of vowels. These instances are usually not indicated by footnotes.[1]

As for the Greek text of the New Testament, the Preface says:

The Greek text used in translating the New Testament was an eclectic one. No other piece of ancient

literature has such an abundance of manuscript witnesses as does the New Testament. Where existing

manuscripts differ, the translators made their choice of readings according to accepted principles of New

Testaments textual criticism. Footnotes call attention to places where there was uncertainty about what the

original text was. The best current printed texts of the Greek New Testaments were used.[2]

In other words, the sources that were used for the NIV Bible are based on critical texts and are usually refered to as “eclectic” texts. An “eclectic text” is composed of elements drawn from various sources.

Let us now look into the “eclectic” sources that the NIV Bible uses and see whether they qualify as God’s “inspired” and “inerrant” words.

3. Biblia Hebraica: The “Inspired” Old Testament?

Biblia Hebraica is one of the best-known critical texts of the Hebrew Old Testament and is the standard source for printed Bibles. It was first edited by Gerhard Kittel. The fouth edition of Biblia Hebraica is called Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) (edited by Karl Elliger and Wilhelm Rudolph) and was authorized by the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft and the United Bible Societies.

Earl Kalland, writing in “How The Hebrew And Aramaic Old Testament Text Was Established” in The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation, describes the material that the translators of the NIV Bible used for the Old Testament:

While the NIV translators generally used the Kittel Biblia Hebraica published by the Privilegierte Wutembergische Bibelanstalt of Stuttgart and available in the United States through the American Bible Society, until the later edition called Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia was made available, other sources within the framework of the various translators’ expertise were considered….

The text of Biblia Hebraica itself, as well as other critical texts, has its own history resulting more or less in an eclectic text. The evaluation of the critical materials in Biblia Hebraica was constantly in review.[3]

The reason why an “eclectic text” such as Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia exists is because the history of the Masoretic Text[4] itself was fluid. There is no textual source that can be called as “the” biblical text. Emanuel Tov, J. L. Magnes Professor of Bible at Hebrew University and the editor-in-chief of the Dead Sea Scrolls publication project, says:

The biblical text has been transmitted in many ancient and medieval sources which are known to us from modern editions in different languages: We now have manuscripts (MSS) in Hebrew and other languages from the Middle Ages and ancient times as well as fragments of leather and papyrus scrolls two thousand years old or more. These sources shed light on and witness to the biblical text, hence their name:

“textual witnesses.” All of these textual witnesses differ from each other to a greater or lesser extent. Since no textual source contains what could be called “the” biblical text, a serious involvement in biblical studies clearly necessitates the study of all sources, including the differences between them. The comparison and analysis of these textual differences hold a central place within textual criticism.[5]

Similarly, Kalland points out that:

The rise of Christianity gave impetus to the Jewish scribes (sopherim) to standardize their texts. Many variations in these texts had already appeared, as is evident from the differences between Greek, Samaritan and Hebrew manuscripts – and even more evident in the Dead Sea Scrolls….

Simply stated, there exists no single text that can be called as the Masoretic Text (except as a generalization). That is one of the reasons why critical texts like Biblia Hebraica exist. The editors of such texts decided what to them was most likely reading of the original. This becomes their text. Then they place in margins the variants and the support for their text and for the variants.[6]

The Kittel’s edition of Biblia Hebraica and its fourth edition Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia is based upon the Codex Leningradensis (L).[7] It is the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible dated to 1008 CE and is based upon the textual work of Ben Asher. One can say that the Biblia Hebraica attempts to be a faithful representation of a single manuscript, i.e., Codex Leningradensis.

But in those places where Codex Leningradensis is defective, or most likely preserves a faulty reading, the critical apparatus is essential for evaluating the other possible readings from other important sources such as Samaritan Pentateuch, the Septuagint, Peshitta, Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) etc. However, scholars have cautioned that Biblia Hebraica does not cite all the readings/evidences and whatever readings/evidences are cited is dependent upon scholar’s insights. Errors can creep in due to assumptions. Ralph W. Klein says:

The common mistake in Old Testament textual studies is to resort to LXX only when the MT, for one reason or another, seems difficult or corrupt. This procedure falls prey to two pitfalls….. In this connection, the following warnings about the uses of apparatuses in Biblia Hebraica must also be issued:

The apparatuses do not cite all synonymous readings or all the evidence for shorter and longer readings. The reason for omitting some of the evidence for variants in LXX or the other versions may be related to the assumption that the MT is correct except where it is obviously difficult or corrupt.

The textual notes in the 1937 edition and in the current reissue are done by a great number of scholars whose presuppositions and assumptions vary and who are gifted with a wide range of text critical insight.

The notes and emendations are often focused only on one word or expression , thus neglecting the wider context in the LXX or other ancient versions.

The apparatuses in the 1937 edition contain errors of fact, as Harry M. Orlinsky has tirelessly pointed out. Many emendations offered are merely conjectures, without manuscript or versional support. While conjectures are at times necessary, they are by definition the most subjective of operations…

In sum, Biblia Hebraica is a helpful collection of variants and scholarly suggestions, but it must be used critically.[8]

Similarly, Waltke also points out the severe shortcomings of Kittel’s Biblia Hebraica as well as modern day editions of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia.

Unfortunately, its critical apparatus swarms with errors of commission and omission, as Orlinsky put it. A new edition, Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia… is now appearing in fascicles. In addition to making minor changes, the editors, K. Elliger and W. Rudolph, inform the reader that the contributers “have exercised considerable restraint in conjectures.”

This welcome restraint, in marked contrast to the earlier editions of Kittel’s Bible, shows that, as the result of the discovery of the DSS, scholars have learned a new appreciation for the credibility of the received text. Unfortunately, the apparatus followed by Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia continues to swarm with errors of omission and commission and therefore cannot be depended on.[9]

Therefore, it is not difficult to imagine that the critical text of the Old Testament as represented by Biblia Hebraica, with all its imperfections and shortcoming, aims for the earliest attainable form of the Hebrew text that can be discerned on the basis of the surviving manuscript evidence.

There is no basis for the claim that Biblia Hebraica represents the “original” and “inspired” text of the Hebrew Bible, although a textual critic can say that it is an attempt to establish the “original” text of the Bible using imperfect and late manuscripts. This is more than clear if one reads the translator’s manual for the preparation of the NIV Bible, where the stress is on using the best possible text of the source material than the “original” text.

The Committee on Bible Translation for the New International Version produced a translator’s manual as a guide for those who were to engage in the endeavor. This manual, in very simple terms relating to the text of the Scripture, declares:

Translators shall employ the best possible texts of the Hebrew and Greek with significant variants noted in the draft notes even though they may not necessarily be in the final printed product. Important text variations which are not adopted in the body of the work should be noted in the margin for the consideration of higher committees.

In general the approach to textual matters should be restrained. The Masoretic O.T. text is not to be followed absolutely if a Septuagint or other reading is quite likely correct. All departures from the M.T. are to be noted by the translators in the margin.[10]

Given the above facts concerning the textual sources of the Old Testament in the NIV Bible, one can accurately say that the Biblia Hebraica is neither “inspired” nor an “original” text. Let us now focus our attention on the sources used for the translation of the New Testament in the NIV Bible.

4. Is The United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament “Inspired” Then?

Well, let us see what Ralph Earle writing in “The Rational For An Eclectic New Testament Text” in The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation says:

What Greek text was used by the translators of the NIV New Testament? It was basically that found in the United Bible Societies’ and Nestle’s printed Greek New Testament which contain the latest and best Greek text available.

In many passage there is no way of being absolutely certain as to what was the original reading because the best Greek manuscripts, both earlier and later ones, have variant readings. In such cases the translators were asked to weigh the evidence carefully and make their own decision.

Of course, such decision was subject to reexamination by the Committee on Bible Translation. In the UBS text, the adopted readings are marked with an A, B, C, or D. Those marked “A” are virtually certain, “B” less certain, “C” doubtful and “D” high doubtful. It is the last, especially, that have to be weighed carefully.[11]

The textual source used for the translation of the NIV New Testament is again a critical text. Does the use of critical text here mean we have the “original” text with us? Dr. David Parker, a New Testament scholar from University of Birmingham, adds a word of caution and differentiate between what is desirable, i.e., to know the “original” text and what can be extracted from the colossal mass of variant readings in the New Testament manuscripts.

We have, however, to distinguish at any rate between the desirable and attainable. Caution rightly prevails in the Introduction to the most common used edition of the Greek New Testament, the small blue volume known as Nestle-Aland:

Novum Testamentum Graece seeks to provide the reader with the critical appreciation of the whole textual tradition… It should naturally be understood that this text is a working text (in the sense of the century-long Nestle tradition); it is not to be considered as definitive, but as a stimulus to further efforts towards redefining and verifying the text of the New Testament.[12]

Dr. Parker emphasizes the fact that the text in the Nestle-Aland’s Novum Testamentum Graece edited by Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland (27th edition, Stuttgart, 1993) was agreed upon by the committee as the “best” reading (hence a working text!) and it has nothing to do with the “original” text.

This text was agreed by a committee. When they disagreed on the best reading to print, they voted. Evidently, they agreed either by a majority or unanimously that their text was the best available. But it does not follow that they believed their text to be ‘original’. On the whole, the textual critics have always been reluctant to claim so much. Other users of the Greek New Testament accord them too much honour in treating the text as definitive.[13]

As far as the Novum Testamentum Graece is concerned, one can say that the committee itself does not make a claim that it restored the “original” text of the New Testament. Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland inform us about the various problems with the committee text.

A “committee text” of this kind is occasionally regarded as problematical, and at times it may be so. In a number of instances it represents a compromise, for none of the editors can claim a perfect acceptance record of all recommendations offered.[14]

Since Nestle-Aland’s critical edition is very complicated to be used in the translation of the New Testament in other languages, there was a growing need for new edition of Greek New Testament which would serve this purpose. This need was materialised in the form of The Greek New Testament (of course, based on Nestle-Aland’s critical text) which has the following features:

- A critical apparatus restricted for the most part to variant readings significant for translators or necessary for establishing the text;

- An indication of the relative degree of certainty for each variant adopted as text;

- A full citation of the representative evidence for each variant selected;

- A second apparatus giving meaningful differences of punctuation. Much new evidence from Greek manuscripts and early versions has been cited. A supplementary volume, providing a summary of the Committee’s reasons for adopting one or another variant reading, will also be published.[15]

This edition is similar to the Nestle-Aland’s critical edition except that it has more details on the textual variants and their relative degree of certainty.

By means of the letters A, B, C, and D, enclosed within “braces” { } at the beginning of each set of textual variants the Committee has sought to indicate the relative degree of certainty, arrived at the basis of internal considerations as well as of external evidence, for the reading adopted as the text.

The letter A signifies that the text is virtually certain, while B indicates that there is some degree of doubt. The letter C means that there is a considerable degree of doubt whether the text or the apparatus contains the superior reading, while D shows that there is a very high degree of doubt concerning the reading selected for the text.[16]

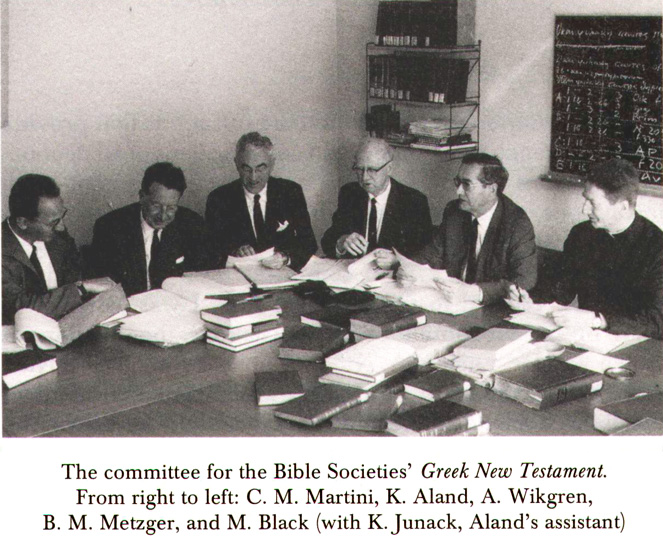

The committee for the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament at one point of time consisted of Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Bruce Metzger, Allen Paul Wikgren and Carlo Maria Martini. The picture below shows them involved in discussions dealing with textual variants in the Greek New Testament. Also notice that on the blackboard, the manuscripts with their short-hand notation are depicted against the letters A, B, C and D for a reading.

A picture is worth a thousand words, especially when a human touch is involved in supposedly the “Word” of God! The committee of textual scholars discussing the variants that would ultimately end up in the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament. Notice the relative certainty for a reading depicted by A, B, C and D on the blackboard.

An example of the text printed in the The Greek New Testament showing the relative degree of certainty is depicted below (more examples can be seen here).

The above image of the Gospel of Mark is taken from The Greek New Testament edited by Kurt Aland, Matthew Black, Carlo M. Martini, Bruce M. Metzger & Allen Wikgren. Note that it provides information about the textual variants and their relative degree of certainty which are needed for the translation.

The relative degree of certainty of the textual variants is again based on the committee’s discussions that included philological processes and a majority vote.

From 1963 onwards, K. Aland worked on a revision of the ‘middle’ text established by Nestle…. The new text was the work of an international committee made up of K. Aland, M. Black, B.M. Metzger, A. Wikgren, and, after the first edition, C.M. Martini. The first edition was published in 1966 by the United Bible Societies (The Greek New Testament). The apparatus contains very few variant readings but, for each one, a large number of witnesses is regularly given.

The choice of variants is based on the majority vote of the committee, and the proportion of votes obtained is indicated by a letter placed at the head of each variation unit. The most notable effect of this combination of philological and democratic processes is that previous choices tend to be repeated.[17]

Surely, if the text has been restored to its “original” form why there is still the relative degree of certainty of variants?

This “committee” text is imperfect at least in one way. The Nestle-Aland/United Bible Societies-Greek New Testament (NA/UBS-GNT) text is an “eclectic” edition. That is, it isn’t a simple reproduction of a particularly good early manuscript that has been found. In other words, it is the product of work done to evaluate available manuscripts to construct what is thought to be the best reflection of the “original” text.

The textual critics have sifted through manuscript fragments, citations within the writings of the fathers, lectionaries, and all sorts of very early translations (such as Syriac, Latin, etc.) to obtain a better picture of a text that was most likely the earliest and may have been “original”. The Greek New Testament text used for the NIV Bible is the product of this scholarship. Gordon D. Fee says that:

… there has emerged a method that may properly be called “eclectic”. Essentially, this means that the “original” text of the NT is to chosen variant by variant, using all the principles of critical judgment without regarding one MS or text-type as necessarily preserving that “original”.

Despite a few notable exceptions, most of the differences that remain among critical texts results from a varying degree of weight given the external evidence.

On the other hand, there is a kind of eclecticism that, when all the criteria are equal, tends to follow Hort and to adopt the readings of the Alexandrian witnesses. This may be observed to a greater degree in the UBS edition and to a somewhat lesser degree in the Greek texts behind RSV and NEB, where early Western witnesses are given a little more consideration.[18]

A call to exercising caution has been made by Moisés Silva on the various issues surrounding the NA/UBS-GNT text. He mentions the fact that this text reflects the opinions of the editors and has nothing to do with the “original” text.

One controversial question has to do with the description of the text as standard by some writers. Not a few scholars have objected to such a description, either because they dispute the value of the edition or because they fear the consequences of adopting a new “textus receptus.” One must sympathize with this sentiment, especially if the term standard is understood in the sense of “definitive”: we can hardly afford to encourage the view that the work of NT textual criticism is for all practical purposes complete.

If anything, the papyrological discoveries and the research of the last several decades has made us more aware of the complexities of the textual history of the Greek NT. Nonetheless, the term may be used simply to indicate that the text in question has received widespread acceptance…. The UBS text reflects a broad consensus and it thus provides a convenient starting point for further work. Far from considering this text as definitive, therefore, we ought to do all we can to improve it.

…. The evidence given in NA26, precisely because it is selective, is more meaningful – and if someone should complain that thereby the presentation reflects the opinions of the editor, the only appropriate answer is that that is precisely what an editor is suppose to give the user.

…. While it is true that most of the variants listed in NA26 have little claim to originality – and thus appear to be somewhat irrelevant for NT exegesis – students make a grave mistake if they fail to become familiar with the realities of textual history broadly considered. Even NA26 is unable to give the user an accurate perception of those realities, but continuous exposure to data in its apparatus at least provides a base of knowledge that informs the scholar’s decisions when struggling with the more substantive variants.[19]

Similarly, Lee Martin McDonald and Stanley Porter in their introduction to the fundamental concepts of textual criticism of the New Testament say that it is unlikely that the reconstructed text will be identical to the original text.

A. Basic Concepts of Textual Criticism

Although most people realize that we do not have the original NT documents (or any original biblical manuscript, or that matter), they do not understand what textual criticism is and what it is designed to do. The goal of textual criticism is easy to explain but extremely difficult to accomplish. Simply stated, its goal is to reconstruct a text as close as possible to the original text from the pen of the author.

At every point where there is a textual variant – where manuscripts present different readings. sometimes as small as a single letter… and sometimes as large as a whole verse or even whole passage (e.g., John 7:53-8:11 or Mark 16:9ff.) – the textual critic must decide which reading is closest to the original.

It is unlikely that the reconstructed (or eclectic) text resulting from such a process would be identical to the original text, and it is virtually certain that the original text would not match any of our extant copies. All of the complete surviving manuscripts are several copy generations removed from the original writing.[20]

The discussion here conclusively shows that the textual source of the New Testament, i.e., NA/UBS-GNT critical edition, used in the NIV Bible is neither “inspired” nor an “original” text. Rather it is a “committee” text, as its contents were decided by a committee of textual critics. It is also a “working” text because the text would change when newer textual sources such as manuscripts are studied and the variants from them added to the text in the later editions.

5. May I Have Your Autograph Please?

Since it has become clearer that the copies of the Hebrew Old Testament and Greek New Testament contained errors (hence the need for a critical text!), it is natural to expect from the evangelicals that the quality of the “accuracy” or “inerrancy” of the Bible would be transferred to the original writings, i.e., the autographs. In gist, the Bible is completely without error in the original autographs.

The weakness of this position is that there are no autographs available for us to certify the claim of “inerrancy” as well as “accuracy”. Moreover, the manuscripts available does not provide us any information about the history of the text even 100 years after the writing of autographs. Helmut Koester says that:

The limitations of purely text-historical procedure in working with classical Greek and Latin texts should not be ignored in NT textual criticism. The reconstruction of a stemma leads back to archetypes of first editions, but not necessarily to the original text.

Even the most successful reconstruction of archetypes in NT textual criticism gives no more than information about the forms of the texts which were in existence at the end of II CE. Like the classical philologian, the NT textual scholar also has to remember that textual corruptions are most frequent during the first decades of the transmission, that is, in the period between the autograph and first edition.

Such corruptions can be more severe in the very first years than in subsequent centuries, no matter whether our oldest manuscript witness comes from the Middle Ages or from III CE.

It does not make much difference how many manuscripts written since the end of II CE have been preserved, since not a single manuscript provides us with a direct insight into the history of the text during the first fifty to one hundred years after the writing of the autograph.[21]

This brings us to the evangelicals’ next line of defence that subscribes to the abundance of the Greek New Testament manuscripts (5600+ and counting) and how they inspire confidence in the current New Testament text. An old maxim about textual criticism is that manuscripts are weighed not counted.[22]

It means that not every manuscript or version is of equal value and that ten copies of a bad manuscript do not make it original. Universal suffrage has no place in textual criticism. No matter how many manuscripts the evangelicals claim to have for their scripture, it is of little or no use as long as the manuscript tradition, for example, of the New Testament is non-uniform down to a sentence. No two manuscripts of the New Testament anywhere in existence are alike.[23]

Furthermore, the studies on New Testament papyri indicate that the text was much more fluid during the first two hundred years of transmission than originally thought.[24] A wide range of textual critics affirm the fluidity of the New Testament text in the first two hundred years. This has been confirmed by research, which has demonstrated that both “orthodox” and “heretical” scribes were indulged in delibrate, theological changes to their biblical text.[25]

6. Ah! Those Fantastic Numbers …

Ralph Earle writing in “The Rational For An Eclectic New Testament Text” in The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation says

… with thousands of Greek manuscripts of the New Testament at our disposal, we can reach a higher degree of certainty with regard to the probability of the best text. It should be added that comparative statistical studies indicate that all Greek manuscripts are in essential agreement on at least 95 percent of the New Testament text. Significant differences exist, then, in less than 5 percent of the total text. And it must be said emphatically that none of these variant readings pose any problem as to basic doctrines of the Bible.

They are intact! We should like to add that all the members of the Committee on the Bible translation are devout Evangelicals, believing in the infallibility of the Bible as God’s Word. We have all sought earnestly to represent as accurately as possible what seems to be, as nearly as we can determine, the original text of the New Testament.[26]

Apart from a leap in the logic of almost equating the “best” text with the elusive and non-existent “original” text, another common subscription of evangelicals is to the numbers that somehow proves “agreement” or “accuracy” of the New Testament. Earle claims that all Greek manuscripts are in essential agreement on at least 95% of the New Testament text.

It does not take a seasoned papyrologist to figure out that only a few Greek manuscripts contain the entire New Testament text! Only about 8% of the manuscripts cover most of the New Testament.[27] Vast majority of the manuscripts contain only portion of the New Testament or exist in fragmentary form.

The textual critics, on the other hand, give completely different picture. Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland in their book The Text Of The New Testament present a table which compares the total number of variant free verses in Nestle-Aland edition with the other critical editions such as that of Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, von Soden, Vogels, Merk, and Bover. This comparison does not take into account the orthographical differences in the variant free verses. The table below:

…gives the count of the verses in which there is complete agreement among the six editions of Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, von Soden, Vogels, Merk, and Bover with the text of Nestle-Aland (apart from orthographical differences).[28]

| Book | Total Number Of Verses | Variant Free Verses-Total | Percentage |

| Matthew | 1071 | 642 | 59.9 % |

| Mark | 678 | 306 | 45.1 % |

| Luke | 1151 | 658 | 57.2 % |

| John | 869 | 450 | 51.8 % |

| Acts | 1006 | 677 | 67.3 % |

| Romans | 433 | 327 | 75.5 % |

| 1 Corinthians | 437 | 331 | 75.7 % |

| 2 Corinthians | 256 | 200 | 78.1 % |

| Galatians | 149 | 114 | 76.5 % |

| Ephesians | 155 | 118 | 76.1 % |

| Philippians | 104 | 73 | 70.2 % |

| Colossians | 95 | 69 | 72.6 % |

| 1 Thessalonians | 89 | 61 | 68.5 % |

| 2 Thessalonians | 47 | 34 | 72.3 % |

| 1 Timothy | 113 | 92 | 81.4 % |

| 2 Timothy | 83 | 66 | 79.5 % |

| Titus | 46 | 33 | 71.7 % |

| Philemon | 25 | 19 | 76.0 % |

| Hebrews | 303 | 234 | 77.2 % |

| James | 108 | 66 | 61.1 % |

| 1 Peter | 105 | 70 | 66.6 % |

| 2 Peter | 61 | 32 | 52.5 % |

| 1 John | 105 | 76 | 72.4 % |

| 2 John | 13 | 8 | 61.5 % |

| 3 John | 15 | 11 | 73.3 % |

| Jude | 25 | 18 | 72.0 % |

| Revelation | 405 | 214 | 52.8 % |

| Total | 7947 | 4999 | 62.9 % |

Table showing the total number of variant free verses in the books of the New Testament when Nestle-Aland edition is compared with the other critical editions such as that of Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, von Soden, Vogels, Merk, and Bover.

It is seen that nearly two-thirds of New Testament text in the seven editions of the Greek New Testament reviewed by Aland and Aland is in agreement with no differences other than in orthographic details. Further, verses in which any one of the seven editions differs by a single word are not counted.[29]

The agreement in the verses of various critical texts of the New Testament from seven major editions from Tischendorf’s to the 25th of Nestle-Aland agree in the wording of 62.9% of the verses of the New Testament. The proportion ranges from 45.1% in Mark to 81.4% in 2 Timothy. Let us take an example of the analysis of the four Gospels. The table below gives the agreement of the verses in the four Gospels taken from the above.

| Book | Total Number Of Verses | Variant Free Verses-Total | Percentage |

| Matthew | 1071 | 642 | 59.9 % |

| Mark | 678 | 306 | 45.1 % |

| Luke | 1151 | 658 | 57.2 % |

| John | 869 | 450 | 51.8 % |

| Total | 3769 | 2056 | 54.5 % |

The percentage agreement of the verses when all the four Gospels are considered is 54.5%. This is very close to the probablity that a tail (or head) appears when a coin is tossed once (i.e., the probablity that a tail or head appears when a coin is tossed is 50%!). It is still a mystery to us from where exactly evangelicals pick-up such fantastic “agreements” between the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament.

If we look at the textual “certainty” of the United Bible Societies’ The Greek New Testament, the results are not too encouraging either. As we have noted above that this edition is used in the translations and is similar to the Nestle-Aland’s critical edition except that it has more details on the textual variants and their relative degree of certainty. The committee of textual critics has sought to indicate the relative degree of certainty by means of the letters A, B, C, and D, enclosed within “braces” { } at the beginning of each set of textual variants.

Their decisions were arrived at the basis of internal considerations as well as of external evidence. “{A}” signifies that the text is virtually certain, while “{B}” indicates that there is some degree of doubt. The letter “{C}” means that there is a considerable degree of doubt whether the text or the apparatus contains the superior reading, while “{D}” shows that there is a very high degree of doubt concerning the reading. These ratings are tabulated below for each editions of The Greek New Testament.[30]

| Ratings / Editions | UBS GNT-1 | UBS GNT-2 | UBS GNT-3 | UBS GNT-3corr | ||||

| {A} Ratings | 136 | 9.4 % | 130 | 8.9 % | 126 | 8.7 % | 126 | 8.7 % |

| {B} Ratings | 486 | 33.6 % | 490 | 33.8 % | 475 | 32.8 % | 475 | 32.9 % |

| {C} Ratings | 702 | 48.5 % | 701 | 48.4 % | 700 | 48.4 % | 699 | 48.4 % |

| {D} Ratings | 122 | 8.4 % | 125 | 8.6 % | 144 | 9.9 % | 144 | 9.9 % |

| Total (Verses) | 1446 | 1446 | 1445 | 1444 |

Table showing the distribution of ratings of verses by editions of the United Bible Societies’ The Greek New Testament. The UBS GNT-1 represents the 1st edition of the United Bible Societies’ The Greek New Testament. On the other hand, the UBS GNT-3corr represents the corrected 3rd edition of the United Bible Societies’ The Greek New Testament.

If we remove the text that is virtually certain, rated as {A}, and take the percentage of the New Testament text (total verses = 7947) that is in doubt, we see that the doubtful text is close to 16.5% in all the three editions of the United Bible Societies’ The Greek New Testament. That brings textual “certainty” to about 83.5% as suggested by the efforts of the committee of textual critics. Again, this is way off from “at least 95%” agreement between the New Testament text in the manuscripts.

In this article, we have discussed the textual sources used for the translation of the NIV Bible. According to the translators of the NIV Bible, the sources used for the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament are their respective critical texts. It was shown that the critical texts, viz., Biblia Hebraica and Novum Testamentum Graece (and also The Greek New Testament based on the latter) are neither “inspired” nor “original” texts.

Rather, they are “eclectic” editions and they aim for the earliest attainable form of the Hebrew and Greek texts that can be discerned on the basis of the surviving manuscript evidence. In other words, there is absolutely no evidence to show that the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament texts used in the translation of the NIV Bible are either “original” or “inspired” by God.

It must be stressed that the critical texts of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament are unique. No texts like this ever existed in the history of Christianity until the advent of modern textual criticism. Nor were texts like these ever used in the translations in the past. The NIV Bible is not unique using such “eclectic” sources for translation. Most of the modern Bibles such as the RSV and the NASV Bibles also use “eclectic” texts of Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament.

The “eclectic” Greek New Testament used in these translations has the Alexandrian text. The KJV Bible, on the other hand, was translated from Erasmus’ printed Greek New Testament that had the Byzantine text-type. Similar arguments, with slight modifications, can be forwarded against the textual sources used for the KJV Bible. It can be shown that the textual sources of the KJV Bible fare no better than the modern day “eclectic” sources, thereby, making the claim of “inspiration” or the “original” text invalid.

Finally, let us end with some thoughtful words of Robert Lane Fox:

In the Old Testament, especially, historians have helped us to realize that we cannot hope to recover the first, the ‘original’ text: it is in others, especially non-historians, that the urge to reconstruct it is still extremely strong. The most recent international committee on the text of the Old Testament defined its task by identifying five thousand important places where a Hebrew word was so puzzling that it might need to be corrected.

It is not just that such corrections raise difficult questions of method (can we really compare Hebrew words with other Semitic words, Arabic for instance, and deduce a new, unattested sense?). It is that there is deeper problem: the starting point, the late Masoretic Hebrew text, already excludes many earlier alternatives.

It is one arbitrary version, hallowed by use, not history. As for the New Testament, in 1966 the United Bible Societies issued a Greek text for students and transators which they, too, described a standard.

Their committee considered that there were two thousand places where alternative readings of any significance survived in good manuscripts and then chose between them. It is not just that by 1975 their Greek text had had to be revised twice because no revision has yet proved free from error and improvement.

The very aim, a standard version, is misleading and unrealistic. From the variety which we have, any standard involves loss: it does not, and cannot, give us exactly what Paul or the Evangelists originally wrote. [31]

And Allah knows best!

References & Notes

[1] The Holy Bible – New International Version, 1973, Hodder & Stoughton: London, p. xii. The entire introduction to the NIV Bible can be seen at “Background of the New International Version Bible“.

[2] ibid.

[3] K. L. Barker (ed.), The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation, 1991, International Bible Society: Colorado Springs, pp. 46-47. (Download).

[4] The Hebrew text of the Old Testament is called the Masoretic text because in its present form it is based on Masora, the textual tradition of the Jewish scholars known as the Masoretes.

[5] E. Tov, Textual Criticism Of The Hebrew Bible, 2001, (2nd Revised Edition) Augsburg Fortress Publishers, p. 2.

[6] K. L. Barker (ed.), The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation, op cit., p. 50.

[7] E. Würthwein (Trans. E. F. Rhodes), The Text Of The Old Testament, 1988, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company: Grand Rapids (Michigan), pp. 104.

[8] R. W. Klein, Textual Criticism Of The Old Testament: The Septuagint After Qumran, 1974, Fortress Press: Philadelphia, pp. 62-63.

[9] B. K. Waltke, “The Textual Criticism Of The Old Testament” in R. K. Harrison, B. K. Waltke, D. Guthrie and G. D. Fee (ed.), Biblical Criticism: Historical, Literary And Textual, 1978, Zondervan Publishing House: Grand Rapids (MI), p. 64.

[10] K. L. Barker (ed.), The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation, op cit., p. 45.

[11] ibid., p. 54.

[12] D. C. Parker, The Living Text Of The Gospels, 1997, Cambridge University Press, p. 3.

[13] ibid.

[14] K. Aland and B. Aland, The Text Of The New Testament: An Introduction To The Critical Editions & To The Theory & Practice Of Modern Text Criticism, 1995, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan, p. 33.

[15] K. Aland, M. Black, C. M. Martini, B. M. Metzger and A. Wikgren (Eds.), The Greek New Testament, 1968 (Second Edition), United Bible Societies, p. v.

[16] ibid, pp. x-xi.

[17] L. Vaganay and Christian-Bernard Amphoux, An Introduction To The New Testament Textual Criticism, 1986, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge (UK), p. 166.

[18] G. D. Fee, “The Textual Criticism Of The New Testament” in R. K. Harrison, B. K. Waltke, D. Guthrie and G. D. Fee (ed.), Biblical Criticism: Historical, Literary And Textual, 1978, Zondervan Publishing House: Grand Rapids (MI), p. 151.

[19] M. Silva, “Modern Critical Editions And Apparatuses Of The Greek New Testament” in B. D. Ehrman and M. W. Holmes (ed.), The Text Of The New Testament In Contemporary Research: Essays On The Status Quaestionis (A Volume In The Honor Of Bruce M. Metzger), 1995, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company: Grand Rapids (MI), pp. 290-291.

[20] L. M. McDonald and S. E. Porter, Early Christianity And Its Sacred Literature, 2000, Hendrickson Publishers, Inc.: Peabody (MA), pp. 578.

[21] H. Koester, An Introduction To The New Testament: History And Literature Of Early Christianity, 1982, Volume II, Walter De Gruyter (Berlin & New York) and Fortress Press (Philadelphia), pp. 41.

[22] This is a rather well-known statement in textual criticism of the Bible. See R. W. Klein, Textual Criticism Of The Old Testament: The Septuagint After Qumran, op cit., p. 74; G. D. Fee, “The Textual Criticism Of The New Testament” in R. K. Harrison, B. K. Waltke, D. Guthrie and G. D. Fee (ed.), Biblical Criticism: Historical, Literary And Textual, op cit., pp. 148-149; L. Vaganay and Christian-Bernard Amphoux, An Introduction To The New Testament Textual Criticism, op cit., pp. 62-63; B. M. Metzger, The Text Of The New Testament: Its Transmission Corruption, And Restoration, 1992, Third Enlarged Edition, Oxford University Press: Oxford (UK), p. 209.

[23] G. A. Buttrick (Ed.), The Interpreter’s Dictionary Of The Bible, 1962 (1996 Print), Volume 4, Abingdon Press: Nashville, pp. 594-595 (Under “Text, NT”); G. D. Fee, “The Textual Criticism Of The New Testament” in R. K. Harrison, B. K. Waltke, D. Guthrie and G. D. Fee (ed.), Biblical Criticism: Historical, Literary And Textual, op cit., p. 128.

[24] E. J. Epp, “The Significance Of The Papyri For Determining The Nature Of The New Testament Text In The Second Century: A Dynamic View Of Textual Transmission” in W. L. Peterson, Gospel Traditions In The Second Century: Origins, Recensions, Text, And Transmission (Christianity and Judaism in Antiquity, Volume 3), 1990, University of Notre Dame Press: Notre Dame (IN), pp. 1-32.

[25] One of first persons to be was accused of changing the scriptures was Marcion. Marcion’s views and treatment of the scriptures were thoroughly critiqued by Tertullian (see his Against Marcion) and Irenaeus (see his Against Heresies). Marcion was not the only person criticized for changing and misusing the scripture.

Bart Ehrman points out that, like Tertullian and Irenaeus, Dionysius of Corinth, Origen and Eusebius also accused their “heretical” opponents of changing biblical text. See B. D. Ehrman, The Orthodox Corruption Of Scripture: The Effect Of Early Christological Controversies On The Text Of The New Testament, 1993, Oxford University Press, pp. 26-27. Futhermore, by the third century CE, variants had become so widely known that Origen was compelled to discuss the important textual variants in his commentaries on scripture. Origen complained that differences in the manuscripts had become great either through copyists’ errors or through “perverse audacity” of others.

He was able to find “spiritual significance” in each of the alternate readings. In his essay, Bruce Metzger discusses two dozen passages in which Origen mentions textual variants; see B. M. Metzger, “Explicit References In The Works Of Origen To Variant Readings In New Testament Manuscripts”, in J. N. Birdsall and R. W. Thomson (ed.), Biblical And Patristic Studies In Memory Of Robert Pierce Casey, 1963, Herder: Frieburg, pp. 78-95; Also see B. D. Ehrman,

“The Text As Window: New Testament Manuscripts And The Social History Of Early Chirstianity”, in B. D. Ehrman and M. W. Holmes (ed.), The Text Of The New Testament In Contemporary Research: Essays On The Status Quaestionis (A Volume In The Honor Of Bruce M. Metzger), op cit., pp. 361-379.

[26] K. L. Barker (ed.), The NIV: The Making Of A Contemporary Translation, op cit., pp. 58-59.

[27] L. M. McDonald and S. E. Porter’s Early Christianity And Its Sacred Literature, op cit., p. 27.

[28] K. Aland and B. Aland, The Text Of The New Testament: An Introduction To The Critical Editions & To The Theory & Practice Of Modern Text Criticism, op cit., p. 29.

[29] ibid.

[30] The table is taken from K. D. Clarke’s “Textual Certainty In The United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament”, Novum Testamentum, 2002, Volume XLIV (No. 2), p. 116. We have slightly modified it for our argument. The 4th edition of The Greek New Testament is not included here because of its unfounded letter rating and has received scathing criticism from fellow textual critics. See Clarke’s article and also L. M. McDonald and S. E. Porter’s Early Christianity And Its Sacred Literature, op cit., p. 581. McDonald and Porter say that the

… first to third (corrected) editions of the UBS text were fairly consistent in their rating criteria and their distributions of ratings, but UBS-4 has experienced severe “grade inflation,” with a disproportionately high number of elevated ratings. For this reason, many scholars appear to be continuing use of the third (corrected) edition , since the text is the same, and to be consulting the fourth edition for the updating of the witnesses to various readings, although these are minimal.

[31] R. L. Fox, The Unauthorized Version: Truth And Fiction In The Bible, 1991, Viking: London, p. 156.